The Effect of Workplace Violence on Depressive Symptoms and the Mediating Role of Psychological Capital in Chinese Township General Practitioners and Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The most existing research has predominantly focused on city rather than township hospitals. This study aimed to explore depressive symptoms and its associated factors among general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out in Liaoning, China in 2016. 2,000 general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals were recruited and 1,736 of them became final subjects (effective response rate: 86.8%). Data on depressive symptoms, workplace violence (WPV), psychological capital (PsyCap), and demographic factors were collected through questionnaires. Hierarchical multiple regression was used to explore the factors related to depressive symptoms. Asymptotic and resampling strategies were applied to examine the potential mediating effect of PsyCap.

Results

The prevalence of depressive symptoms among the participants was 49.9%. Workplace violence was positively associated with depressive symptoms, whereas psychological capital and its components of hope, optimism and resilience were negatively associated with depressive symptoms. Psychological capital and its components of hope, optimism and resilience all played partial mediating roles between workplace violence and depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

Nearly half of general practitioners and nurses surveyed suffered from depressive symptoms. Reduction of workplace violence and development of psychological capital can be targeted for interventions to combat depressive symptoms.

INTRODUCTION

Workplace violence (WPV) was defined as physical assaults and threats of assault directed towards persons at work [1]. Furthermore, WPV-related depressive symptoms have been in the limelight around the world. Depression can be regarded as one of common disorders of psychological distress and it mainly manifests as depressed emotion, slow thinking, poor sleep, reduced initiative, pessimism, and even suicidal thoughts [2]. According to a study, this showed that 36.3% of WPV victims presented intermediate depressive symptoms and 16% probably had major depression [3]. Depressive symptoms can develop into depression causing the affected person to function poorly at school, at work, and in the family, or even worse, leading to suicide [4].

Doctors and nurses, as particular occupational population, undertake the responsibilities of curing diseases and promoting health, which can predispose them to high occupational stress inevitably leading to distressed emotion [5]. Due to this special occupational environment, there is high prevalence of depressive symptoms among doctors and nurses. A study by Saijo et al. [6] found that about 46.7% of nurses had depressive symptoms in Japan. In China, Gong et al. [7] reported that 38% of nurses had depressive symptoms. Shen et al. [8] also revealed that the prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese physicians was 31.7%. Medical staff with depressive symptoms could seriously influence their own quality of life and medical services [9]. Noticeably, depressive symptoms among general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals should be highlighted. On one hand, China is still a big agricultural country with huge rural population [10]. Rural patients may bring about serious economic burden of the society if their health problems are not cured effectively due to reduced medical service [11]. On the other hand, it is township hospitals that provide primary medical service to rural residents [12]. However, understaffed general practitioner and nurses are faced with less advanced medical devices and equipment [13], high workload but low income [14], few promotion opportunities [15], and more challenges in WPV [16], all of which may lead to their depressive symptoms.

WPV has been identified as risk factors for depressive symptoms [17,18]. WPV can be defined as abuse, threats and attacks, which pose a major threat to employees’ safety or health in their work environment [1]. WPV occurs commonly in hospitals. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) reports, 8% to 38% of medical staff suffered physical violence at work, with a large proportion suffered verbal abuse or threat [19]. In China, most existing research has focused on city rather than township hospitals [20], approximately 50% of medical staff in city were reported to experience a form of violence at work in a year [15]. Hospital violence not only has an impact on organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover of health workers, but also affects their physical and mental health such as depressive symptoms [17,21,22]. However, research in other countries has determined there is higher risk to rural general practitioners and nurses compared to city hospitals [23,24]. In China, township hospitals are characterized by relatively outdated medical devices and equipment, along with the shortage of health human resources, and accordingly, medical staff there often cannot provide high quality medical services [12], which may lead to more conflicts with patients, including hospital violence. Thus, we will explore the association and hypothesize WPV may be an important contributing factor of depressive symptoms in the study.

Psychological capital (PsyCap), as a positive psychological resource which can be measured, plays a vital role in both work performance and physical and mental health of employees [25,26]. Based on positive psychology, PsyCap is defined as “a positive state of mind exhibited during the growth and development of an individual” [27]. PsyCap consists of four core elements: hope, optimism, resilience and self-efficacy [28]. Hope is defined as “a positive motivational state that is based on an interactively derived sense of successful agency (goal-directed energy) and pathways (planning to meet goals).” Optimism is an attributional mode which explains positive events as results of internal, permanent and general causes whereas negative events as results of external and temporary causes. Resilience is usually considered as the developable abilities to rebound or bounce back from tragedy, frustration and failure or even positive events. Self-efficacy refers to individual’s belief about their capability to motivate the intention, cognitive resources and the necessary action to finish a specific task within established environment [28]. Prior research suggested that PsyCap had significant negative effects on depressive symptoms. For example, Liu et al. [29] reported that PsyCap and its components (hope, optimism, resilience and self-efficacy) were all negatively related to depressive symptoms among Chinese male correctional officers.

On the other hand, in the studies on the relationship between depressive symptoms and its associated factors, PsyCap and its components often worked as mediators combating depressive symptoms. For instance, Hao et al. [30] reported that PsyCap, hope and optimism were identified as mediators on the associations between work-family conflict and depressive symptoms among Chinese nurses. A previous study also found that resilience partially mediated the relationship between psychological stress and depressive symptoms among Chinese bladder and renal cancer patients [31]. In addition, another study indicated that self-efficacy could play a mediating role on the association between big five personality and depressive symptoms among Chinese unemployed population [32]. However, the potential effects of PsyCap on the association between WPV and depressive symptoms have not been examined among general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals. Thus, we hypothesize that the PsyCap will work as a mediator in the relationship between WPV and depressive symptoms in the present study.

In light of the above concerns, the aim of the present study was to examine the relationship between WPV and depressive symptoms among general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals. More importantly, we aimed to confirm the integrative effects of PsyCap on depressive symptoms after adjusting for the demographic variables.

METHODS

Ethics statement

The study procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards and approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University (CMU62083011). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Information collected from all subjects was kept confidential and anonymous.

Study design and data collection

A cross-sectional study was carried out in Liaoning province, China, in 2016. Multi-staged sampling method was applied in our study. Firstly, according to the geographical distribution, 7 cities were randomly selected in Liaoning; secondly, from each city, a county or region was randomly selected. Finally, participants were selected from each chosen county or region by cluster sampling. After obtaining the informed consent, a self-administered questionnaire was distributed to each subject. The questionnaires were sent to 2,000 recruited general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals and 1,736 of them became the final subjects (effective response rate: 86.8%).

Measurement of depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured with Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [33]. It is a brief, self-report questionnaire to measure individual’s feeling in the past week, which has been reported to have good reliability and validity among rural populations in China [34]. The CES-D comprises 20 items and each item have four responses ranging from 0 ‘rarely’ to 3 ‘most or all of the time.’ The total score ranges from 0 to 60, and higher score indicates severer depressive symptoms. Subjects who had a CES-D ≥16 were defined to belong to ‘depressive symptoms’ group [33]. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.887 in this study.

Measurement of workplace violence

The Chinese version of workplace violence scale (WVS) was applied to assess the frequency of WPV experienced by healthcare workers [35]. The Chinese version of WVS, developed by Wang, was originated from Schat version of WVS [36]. The Chinese version of WVS is divided into five dimensions including physical assault, emotional abuse, threat, verbal sexual harassment and sexual assault; each dimension has one item, with 5 items in total. Each item has four responses ranging from 0 to 3 (0=never, 1=1 time, 2=2–3 times, 3=≥4 times). The total score ranges from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating a higher frequency of experiencing violence. The Chinese version of WVS has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity among individuals in China [37]. In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient for the total scale was 0.784.

Measurement of psychological capital

The Chinese version of the 24-item Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ) was used to measure PsyCap [38]. The 24-item PCQ consists of 4 dimensions including self-efficacy, hope, resilience and optimism [39]. Each item has six responses, ranging from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 6 ‘strongly agree’. The higher average score for each dimension indicates the higher hope, optimism, resilience and self-efficacy level; the higher average score for total scale indicates more PsyCap individual has. The Chinese PCQ has demonstrated adequate reliability and construct validity of the PCQ among multiple samples [40,41]. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for self-efficacy, hope, resilience, optimism and PsyCap were 0.884, 0.892, 0.731, 0.726, and 0.920, respectively.

Demographic variables

Five demographic variables were obtained from the self-reported questionnaire, including age, marital status, monthly income, occupation and education. Age was classified as <30, 30 to 50, and >50 years old. Marital status was categorized as unmarried, married/cohabitation and divorced/widowed/separated. Monthly income was divided into <2,000, 2,000 to 4,000, and >4,000 Renminbi (RMB). Occupation was classified as doctors and nurses. Education background was divided into senior high school or under, junior college and undergraduate or above.

Statistical analysis

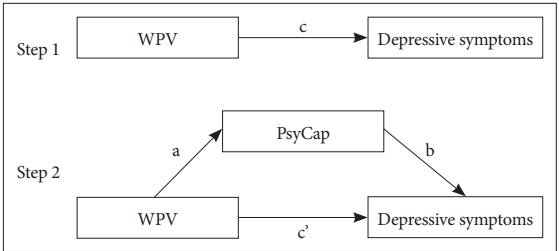

The mean depressive symptoms score in different categories of demographic factors were examined by t-test or one-way ANOVA. Pearson correlation analysis was used to analyze the correlation between WPV, PsyCap and depressive symptoms. Hierarchical linear regression analyses were applied to explore the mediation of PsyCap in the relationship between WPV and depressive symptoms. Asymptotic and resampling strategies were used to examine PsyCap as a potential mediator on the association between WPV and depressive symptoms [42]. WPV was modeled as independent variable, with depressive symptoms as dependent variable, PsyCap and its components as mediating variables (Figure 1), and demographic factors as covariates. In the first step, the aim was to test whether the relationship between workplace violence and depressive symptoms was significant (the c path); in the second step, the aim was to examine the mediation of PsyCap (the a*b products). If the effect of WPV on depressive symptoms (c’ path coefficient) in the second step was smaller than the c path coefficient in the first step, or was not significant, the mediation of PsyCap possibly existed. The bootstrap estimated in our study was based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. A bias-corrected and accelerated 95% confidence interval (BCa 95% CI) was conducted for each a*b product, and a BCa 95% CI excluding 0 indicated significant mediation.

Theoretical model of the mediation of PsyCap on the association between WPV and depressive symptoms. c: associations of WPV with depressive symptoms; a: associations of WPV with PsyCap; b: association between PsyCap and depressive symptoms after controlling for the covariates; c’: associations of WPV with depressive symptoms after adding PsyCap as a mediator. WPV: workplace violence, PsyCap: psychological capital.

All Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values <10, was considered no existence of collinearity in hierarchical multiple regression. All the statistical analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows (version 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with two-tailed probability value of <0.05 considered to be statistically significant. All statistical tests were two-sided (α = 0.05).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

About 49.9% of the participants had depressive symptoms (CES-D≥16). The average age of the participants was 41.09± 9.84 years; the depressive symptoms score of the participants was 16.16±8.99 and the WPV score was 1.67±2.62 (mean±SD). Demographic characteristic of subjects and distributions of depressive symptoms were shown in Table 1. Marital status and monthly income were significantly associated with depressive symptoms (p<0.05). As for marital status, the scores of those who were divorced, widowed or separated (5.1%) were higher than others. 459 (26.4%) out of the respondents’ monthly income were below 2,000 RMB, with higher score of depressive symptoms than others.

Correlations between study variables

Correlation coefficients between continuous variables were presented in Table 2. WPV was significantly and positively associated with depressive symptoms, whereas PsyCap and its components including self-efficacy, hope, resilience and optimism were significantly and negatively associated with depressive symptoms; WPV was significantly and negatively associated with PsyCap and its components.

Mediating roles of PsyCap and its components

Given the associations between demographic variables (marital status and monthly income) and depressive symptoms, these demographic variables were added as control variables in block 1 in hierarchical multiple regression analyses, as shown in Table 3. In block 2, WPV was positively and significantly related to depressive symptoms (β=0.399, p<0.01); in block 3A, PsyCap was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (β=-0.420, p<0.01) and the effect of WPV on depressive symptoms was smaller (β=0.309, p<0.01) compared with that in block 2, which indicated that PsyCap could probably become a partial mediator on the association of WPV with depressive symptoms. Likewise, in block 3B, three dimensions of PsyCap including hope (β=-0.187, p<0.01), resilience (β=-0.095, p<0.01) and optimism (β=-0.250, p<0.01) were significantly and negatively associated with depressive symptoms and the effect of WPV on depressive symptoms was also smaller (β=0.299, p< 0.01) compared with that in block 2, indicating that hope, resilience and optimism could also partially mediated the association of WPV with depressive symptoms.

Associations of WPV, PsyCap and its components with depressive symptoms and mediating roles of PsyCap and its components

The mediating effect of PsyCap and its components were examined in Table 4. WPV had a negative association with PsyCap and its components (the a path); PsyCap and its components had significant and negative correlations with depressive symptoms after controlling for WPV (the b path). The product of a*b indicated that with the exception of self-efficacy, PsyCap (a*b= 0.090, BCa 95% CI: 0.066, 0.114), hope (a*b=0.037, BCa 95% CI: 0.022, 0.055), resilience (a*b=0.018, BCa 95% CI: 0.008, 0.037) and optimism (a*b=0.049, BCa 95% CI: 0.034, 0.066) all significantly and partially mediated the association between WPV and depressive symptoms.

Proportion of the total effect of the WPV on depressive symptoms (the c path) mediated by PsyCap, hope, resilience and optimism were calculated with the formula (a*b)/c to assess the mediating effect size. The proportion of mediation of PsyCap, hope, resilience and optimism were 22.53%, 9.27%, 4.51%, and 12.28%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This large-scale cross-sectional study of general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals was conducted in Liaoning province in the northeastern region of China, which was the first one to examine the association between WPV and depressive symptoms and the mediating role of PsyCap on the relationship in China. Our findings revealed that 49.9% of the general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals had depressive symptoms (CES-D≥16), which was higher than the prevalence of metropolitan doctors (28.1%) [43], migrant workers (23.7%) [44], and general public in China (33.3%) [45]. Besides, the mean score of depressive symptoms among the subjects (16.16±8.99) was also much higher than the average score of general population in urban China (13.24±10.33) [45]. These results indicated that general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals had relatively severe depressive symptoms. Therefore, urgent efforts should be made to prevent and reduce these symptoms among general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals.

In this study, WPV was found to be positively related to depressive symptoms, which echoed the findings of similar studies [16,17,43]. General practitioners and nurses devote themselves to helping patients to alleviate the pain and improve their quality of life. However, when general practitioners and nurses experience violent incidents such as accusations or abuse from patients, they are likely to have serious psychological imbalance in return, which can develop into negative emotion or stress [46]. On the other hand, since general practitioners and nurses in China are always busy at taking care of a large number of patients, there is little time left to relax themselves or communicate with others to release their negative emotion and stress [47]. Over time, medical staff may suffer from mental disorders such as depression [48].

In China, the continuous reform of the healthcare system [4], increased occupational stress [49], and the increasingly serious doctor/nurse-patient conflicts have resulted in violent incidents occurring frequently in health sector [47]. In our study, after the adjustment for control variables, WPV accounted for 15.9% of the total variance in depressive symptoms, confirming its important impact on depressive symptoms. Therefore, intervention strategies should be carried out to help general practitioners and nurses receive more respect from rural residents, improve their medical technology, and promote communication between doctors/nurses and patients in order to reduce occurrence of violent incidents and negative impact of WPV on mental health among general practitioners and nurses in township hospitals in China.

PsyCap and its components (hope, resilience and optimism) were found to play partial mediating roles in the relationship between WPV and depressive symptoms, which confirmed our hypothesis. The results suggested that workplace violence could reduce the level of general practitioners and nurses’ PsyCap; subsequently, the reduced PsyCap could lead to their depressive symptoms. In other words, PsyCap and its components (hope, resilience and optimism) could help general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals to combat depressive symptoms. This result was in accordance with previous studies that verified the mediating effect of PsyCap in relationships among many occupational psychological outcomes. For instance, PsyCap could act as a mediator on the associations of depressive symptoms with occupational stress [50], and perceived organizational support [29]. Individuals who experienced WPV would feel angry, unfair and sad, along with decreased level of PsyCap, especially hope, resilience and optimism. Hope and optimism were found to be negatively associated with depressive symptoms, as they could help individuals to actively reduce or release psychological stress and negative emotions [51]. Previous studies also showed that resilience was significantly and negatively associated with depressive symptoms, since resilience could guide individual to bounce back from tragedy, frustration or failure [52]. As PsyCap can be measured, developed and effectively managed [38], the findings from our study encourage hospital managers to adopt effective strategies to improve PsyCap to combat depressive symptoms. In addition, in this study, we found that PsyCap as a whole had a greater mediating effect than that of each component (hope, resilience and optimism) alone, which suggested that managers might focus on the development of total PsyCap rather than its individual components. In brief, effective interventions should be undertaken to reduce WPV and to improve PsyCap so as to relieve depressive symptoms among general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals.

However, several limitations must be mentioned. First, we applied a cross-sectional design, which limited us to draw conclusion on the casual relationships between the variables investigated. Longitudinal studies should be conducted in the future. Secondly, all data collected in this study were obtained through self-reported questionnaires, which could introduce recall bias or response bias. Thirdly, the participants were restricted in rural areas of Liaoning province, in northeastern region of China. Thus, caution should be taken when attempting to extrapolate the results to health workers in township hospitals in other regions of China.

In summary, based on this cross-sectional survey, our findings revealed that a large percentage of general practitioners and nurses surveyed in Chinese township hospitals had depressive symptoms and also suffered severe WPV which was significantly and positively related to depressive symptoms. PsyCap and some of its components (hope, resilience and optimism) played partial mediating roles in the relationship between WPV and depressive symptoms. Our results highlighted the importance of intervention on WPV and PsyCap for the reduction of depressive symptoms among general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the administrators in the study hospitals who assisted in obtaining written informed consent for the survey and in distributing questionnaires to the subjects.

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Lie Wang, Chi Tong. Data curation: Lie Wang, Chi Tong, Chunying Cui, Yifei Li. Formal analysis: Chi Tong, Chunying Cui. Validation: Lie Wang. Writing—original draft: Chi Tong. Writing—review & editing: Lie Wang, Chunying Cui, Yifei Li.