Predictors of Psychiatric Outpatient Adherence after an Emergency Room Visit for a Suicide Attempt

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the potential correlation between baseline characteristics of individuals visiting an emergency room for a suicide attempt and subsequent psychiatric outpatient treatment adherence.

Methods

Medical records of 525 subjects, who visited an emergency room at a university-affiliated hospital for a suicide attempt between January 2017 and December 2018 were retrospectively reviewed. Potential associations between baseline characteristics and psychiatric outpatient visitation were statistically analyzed.

Results

107 out of 525 individuals (20.4%) who attempted suicide visited an outpatient clinic after the initial emergency room visit. Several factors (e.g., sober during suicide attempt, college degree, practicing religion, psychiatric treatment history) were significantly related to better psychiatric outpatient follow-up.

Conclusion

Several demographic and clinical factors predicted outpatient adherence following a suicide attempt. Therefore, additional attention should be given to suicide attempters who are at the risk of non-adherence by practitioners in the emergency room.

INTRODUCTION

Death by suicide and suicide attempts (SA) are considered serious social problems and critical public health issues. According to WHO statistics, more than 800,000 people die due to suicide every year globally, accounting for 1.4% of all mortality worldwide [1]. Death from suicide globally has decreased over the past 2 decades, however, the suicide rate in South Korea is the highest among the OECD countries (24.6 suicide deaths per 100,000 in 2016) [2,3]. Suicide is also the leading cause of death in adolescents and young adults in South Korea [4]. The economic burden for suicide in South Korea was estimated to be 6,448 billion South Korean Won in 2017, which is equivalent to approximately 5.5 billion United States Dollar [5].

Suicide attempt is known to be an important risk factor for suicide death [6,7]. In fact, 10% of suicide attempts subsequently lead to suicide within 10 years [8]. In addition, psychiatric disorders are significantly related to suicide death and SA [9-11]. Therefore, psychiatric evaluation and treatment of subjects who attempt suicide is very important in preventing suicide death [12,13]. Many individuals who attempt suicide visit the emergency room (ER) seeking for primary treatment, and concomitant psychiatric intervention is highly important to prevent further suicide attempts. However, the actual follow-up rate for psychiatric visit after ER discharge is relatively low [14-16]. So far, few studies have evaluated the psychiatric adherence of individuals attempting suicide, therefore, this study aimed to investigate factors affecting outpatient follow-up of patients who visited the ER for SA.

METHODS

Study design and participants

The study is a retrospective study and data were collected using medical record review. Between January 2017 and December 2018, all patients who visited the ER at the Konkuk University Medical Center, a tertiary hospital located at Seoul, Korea for SA were included. All the patients who visited the ER for suicide attempts were seen by psychiatric residents and an outpatient appointment was made in all cases based on the policy of the hospital. The treatment adherence was defined as visiting the psychiatric outpatient clinic of Konkuk Medical Center at least once after discharge from the ER. In case of subjects who were admitted to medical or psychiatric ward directly from ER, visiting psychiatric outpatient clinic after discharge from the ward was regarded as treatment adherence. Subjects who never visited the psychiatric outpatient clinic after discharge were assigned to the non-adherent group.

Measures

Sociodemographic information (i.e., gender, age, education, type of health insurance, religion, and household members) and clinical data (i.e., types of SA, number of previous SA, previous psychiatric admission or treatment history, psychiatric family history and primary psychiatric diagnosis made by psychiatric residents through unstructured interview) were obtained. Information related to ER visit included: 1) if patients visited the ER on a weekday or a weekend, 2) if patients came to the ER by themselves or were brought by someone else, 3) whether anyone accompanied the individual who attempted suicide when they visited ER or not and 4) whether the patients was in a drunken state during SA or sober. Additionally, whether or not the patient needed medical or surgical attention in the ER because of the SA was captured. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Konkuk University Medical Center (KUMC 201910026).

Statistical analysis

The student’s t-test and chi-square test were used to compare variables between the adherent and non-adherent groups. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to examine the relation of psychiatric outpatient follow-up and patient characteristics. Variables that showed significant difference in the t-test or chi-square test (college graduation, religion, alcohol intake during SA, psychiatric treatment history, previous SA history and psychiatric admission history) were entered as independent variables predicting outpatient clinic visit. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Among the 525 patients who visited our ER for a SA during the period. Eighty-four % of the patient were discharged from ER and 16% were hospitalized (6.1% at psychiatric ward and 9.9% at general ward). A total of 107 (20.4%) showed-up at the outpatient clinic after discharge from ER or ward.

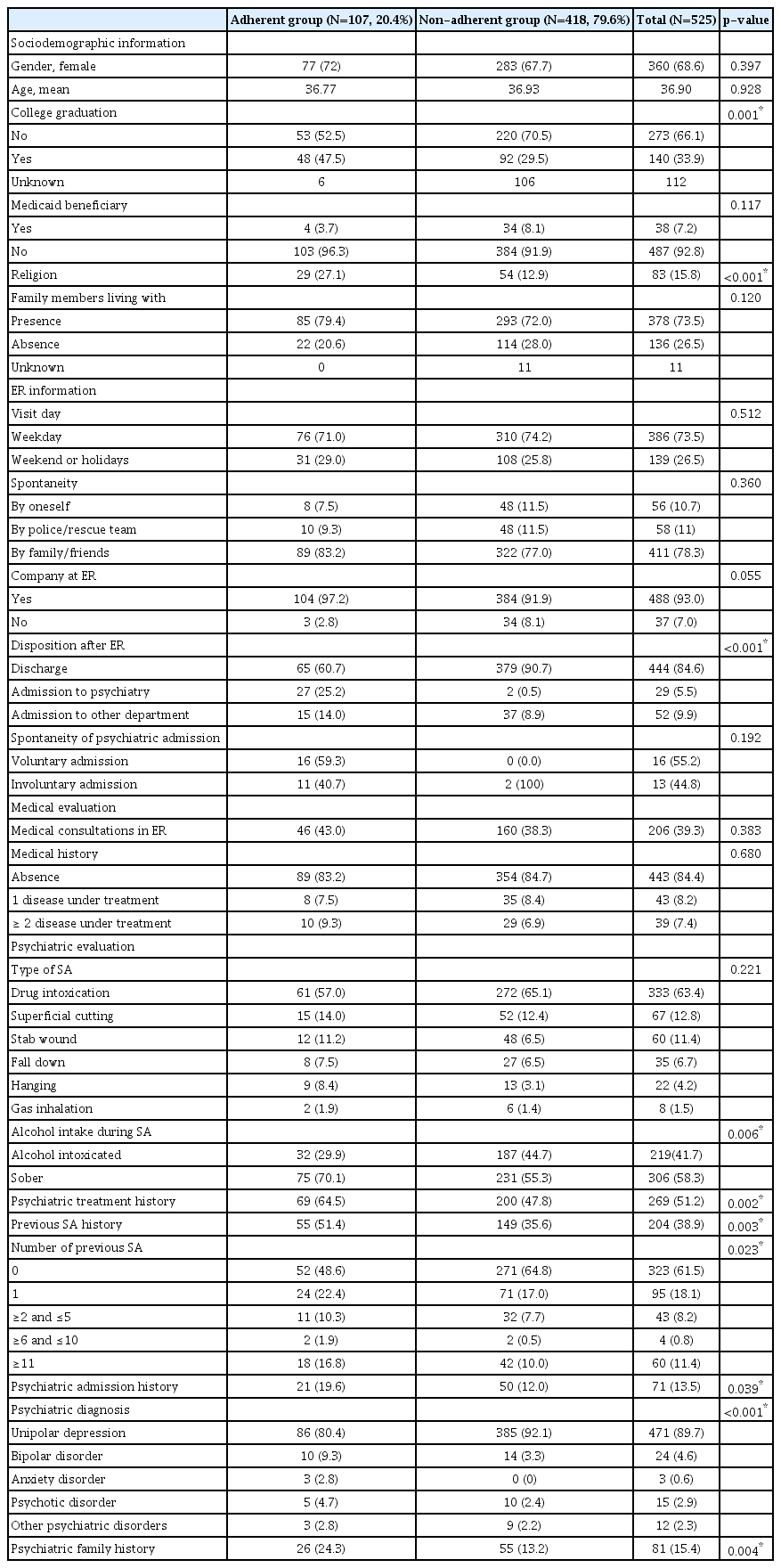

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between groups (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference between adherent and non-adherent groups in gender, age, type of health insurance, living with family members, spontaneity of ER visit, company at ER, type of SA, other department referral, and medical history. However, there were more college graduates in the adherent group compared with the non-adherent group (47.5% vs. 29.5%, respectively; p=0.001). The adherent group was more likely to have religion compared with the non-adherent group (27.1% vs. 12.9%, respectively; p<0.001). The non-adherent group tended to attempt suicide while they were drunken (44.7% vs. 29.9%, respectively; p=0.006). The adherent group was more likely have a history of psychiatric treatment (64.5% vs. 47.8%, respectively; p=0.002), history of psychiatry admission (19.6% vs. 12.0%, respectively; p=0.039), history of previous SA (51.4% vs. 35.6%, respectively; p=0.003) and family history of psychiatric treatment (24.3% vs. 13.2%, respectively; p=0.004). Higher proportion of patients who were admitted directly from the ER showed up in the outpatient clinic than patient who were discharged from the ER (p<0.001), however, there were no significant difference according to spontaneity of the admission (p=0.192). There were significant differences in terms of psychiatric diagnosis and number of previous SA between the groups.

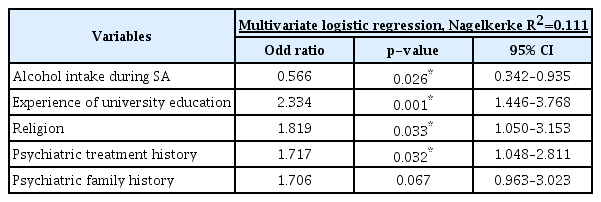

In the multivariate logistic regression analyses (Table 2), drunken state during SA was a risk factor of psychiatric outpatient follow-up loss (odd ratio=0.566, p=0.026). College graduation (odd ratio=2.334, p=0.001), having a religion (odd ratio=1.819, p=0.033) and psychiatric treatment history (odd ratio=1.717, p=0.032) were protective factors of psychiatric outpatient treatment adherence. Psychiatric family history was not significantly different in multivariate logistic regression analysis (odd=1.706, p=0.067).

DISCUSSION

Among the 525 subjects who visited our ER after SA included in this study, 20.4% (107) visited a psychiatry outpatient department after discharge. In our study, factors demonstrated to predict psychiatric outpatient follow up after SA were psychiatric treatment history, drunken state during SA, practicing religion and a college degree.

Subjects who have experience with psychiatric treatment tend to be more adherent to psychiatric outpatient follow-up compared with those who have no psychiatric treatment experience. Results of previous studies are consistent with this study [17-20]. Suokas et al. [18] reported that patients receiving prior psychiatric treatment were referred more often for psychiatric consultation in the ER. Cremniter et al. [19] reported that a history of psychiatric treatment is the best predictor of compliance in psychiatric emergency patients and emphasized that non-compliance in the ER was the most important predictor of deterioration. This result implies that subjective experience and attitude formed by previous psychiatric treatment could influence psychiatric adherence.

Previous studies have demonstrated inconclusive results on the relationship between past SA and psychiatric adherence. Lee et al. [21] reported that the compliant group had more previous SAs compared to the non-compliant group, however, these results were not clinically significant. A study by Costemale-Lacoste et al. [14] also demonstrated similar results. In their multi-site prospective study, they investigated factors that affect outpatient treatment engagement after a SA and reported that a previous SA did not predict 1-month and 3-month follow-up. Here, it was demonstrated that patients who had attempted suicide in the past showed better outpatient treatment adherence; two possible explanations exist for this observation. First, patients who have attempted suicide multiple times are more likely to have more serious underlying psychiatric illnesses compared with patients who did not and are, therefore more likely to seek treatment. Alternatively, there could be a link between a previous SA and compliance related to the patient’s satisfaction with previous medical treatment. It has been suggested that patient’s satisfaction with medical service is highly important in terms of compliance in psychiatric [22] and medical patients [23]. A patient who attempted suicide may have experienced various medical services and the variety of degree of their subjective satisfaction might have contributed to the inconclusive results of previous studies. However, since we have not investigated detailed past psychiatric treatment experiences of patients who attempted suicide, it was not possible to demonstrate a relationship between previous treatment experiences and psychiatric compliance.

It is well known that problematic alcohol use is a risk factor for suicide death and SA [24-26]. These include disinhibition, impulsivity, poor judgment, and underlying personality disorder in patients with problematic alcohol drinking [27-32]. In addition, alcohol use is also associated with low treatment adherence, which is related to the fluctuating nature of the personality of alcohol-dependent patients [33]. This study also suggests that patients who were drunken during their SA had low outpatient adherence, and that these patients required further intervention. This result is consistent with those of many previous studies [16,34-37]. SA patient who attempted suicide while drunken may have poor insight on their action and may not follow medical advice provided.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report that religion is associated with improved outpatient adherence in individuals attempting suicide. In previous studies, religion has also been known to act as a protective factor in various psychiatric conditions including depression, alcohol use disorder, PTSD and suicide attempts [38-41]. In addition, religion is related with increased resilience (i.e., one’s ability to overcome adversities or trauma) [42]. Possible mechanisms between religion and mental health include greater feelings of self-efficacy and self-regulation, behavioral restraint and enhanced social support [41].

College graduation is also a predictor of psychiatric follow-up. Previous studies have reported that subjects with higher levels of education tend to use mental health care services more frequently compared with a lower level of education group [43,44]. Costemale-Lacoste et al. [14] also reported that postgraduate studies predict better specialized out-patient treatment engagement at a 1-month follow up. Individuals achieving higher levels of education may be more informed about psychiatric illness, treatment and resources. Furthermore, higher education is related to higher socio-economic status, another crucial factor impacting medical treatment in most countries.

There are some limitations of our study, including the retrospective nature which does not guarantee that potential confounding factors that could influence results are eliminated. Additionally, the reasons why some patients attended psychiatric outpatient follow-ups and some others did not were not explored. There is a possibility that patients who received treatment after suicide attempts in the psychiatric clinic other than Konkuk Medical Center were regarded as non-adherent subjects. Finally, multiple definitions of treatment adherence exist; here it was defined as one visit to the outpatient clinic, therefore information on long-term follow-up was not assessed. Evaluation of follow-up duration might be a more accurate way to evaluate treatment adherence.

However, while previous studies have focused on the certain proportion of suicide attempters, we could collect the data from all patients who attempted suicide and visited an ER at a tertiary general hospital for relatively long period. Therefore, we could identify factors which are related to subsequent outpatient treatment adherence and firstly report that religion is positively related to treatment adherence in suicide attempters. Based on our findings, clinicians who encounter suicide attempters in ER may adopt specific strategies [45,46] designed to improve treatment adherence for those who are at the risk of non-adherence. Further studies that specifically assess factors influencing a patient’s treatment follow-up are warranted as they may further improve compliance for care provided after a suicide attempt.

Acknowledgements

None.

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Hong Jun Jeon. Data curation: Seungbeom Yang, Jong Won Kim. Formal analysis: Hong Jun Jeon. Methodology: Hong Jun Jeon. Project administration: Doo-Heum Park. Supervision: Jee Hyun Ha, Seung-Ho Ryu. Writing—original draft: Jin Shin, Hong Jun Jeon. Writing—review & editing: Jin Shin, Hong Jun Jeon.