Comparative Study of Personality Traits in Patients with Bipolar I and II Disorder from the Five-Factor Model Perspective

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The distinguishing features of Bipolar I Disorder (BD I) from Bipolar II Disorder (BD II) may reflect a separation in enduring trait dimension between the two subtypes. We therefore assessed the similarities and differences in personality traits in patients with BD I and BD II from the perspective of the Five-Factor Model (FFM).

Methods

The revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) was administered to 85 BD I (47 females, 38 males) and 43 BD II (23 females, 20 males) patients. All included patients were in remission from their most recent episode and in a euthymic state for at least 8 weeks prior to study entry.

Results

BDII patients scored higher than BD I patients on the Neuroticism dimension and its four corresponding facets (Anxiety, Depression, Self-consciousness, and Vulnerability). In contrast, BD II patients scored lower than BD I patients on the Extraversion dimension and its facet, Positive emotion. Competence and Achievement-striving facets within the Conscientiousness dimension were significantly lower for BD II than for BD I patients. There were no significant between-group differences in the Openness and Agreeableness dimensions.

Conclusion

Disparities in personality traits were observed between BD I and BD II patients from the FFM perspective. BD II patients had higher Neuroticism and lower Extraversion than BD I patients, which are differentiating natures between the two subtypes based on the FFM.

INTRODUCTION

Bipolar I Disorder (BD I) and Bipolar II Disorder (BD II) have been demonstrated to exist in a disease spectrum.1-3 Within DSM-IV diagnostic boundaries, BD II characterized by recurrent depressive episodes interspersed with hypomania differs from BD I in that only hypomania, not mania. Thus, BD I and BD II are currently distinguished by the intensity of cross-sectional manic symptoms. Accordingly, BD II has been conventionally regarded as a milder form of BD I on the basis of manic symptomatology. However, clinical researches to date strongly indicate that BD II is at least as severe as BD I; moreover, BD II is more serious and chronic than is BD I from the aspect of depressive symptomatology. Longitudinally, BD II patients are at higher risk of a chronic symptomatic course and BD II is dominated by the depressive phase of illness rather than the period of hypomania.4 In addition, BD II patients have a poorer overall quality of life than do BD I patients even during sustained periods of euthymia.5

The clinical features distinguishing BD II from BD I may reflect a separation in enduring trait dimension, such as personality traits, between BD I and BD II. For example, individuals with a certain BD subtype showing predominantly depressive symptoms may exhibit a property of depressive personality traits, such as high Neuroticism or Harm avoidance. Additionally, discrimination amongst bipolar subtypes may fundamentally lie in disparate personality traits. To date, however, there have been few comparative studies of personality traits in BD I and BD II patients.

Most of what is known about the personality traits of patients with BD comes from studies focused on BD I patients or mixed samples of patients with BD I and II. The studies using the NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI) to assess personality traits revealed that patients with BD had significantly higher Neuroticism scores than did normal controls.6,7 Studies employing the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) or the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (TPQ) reported that patients with BD showed higher scores on Harm avoidance than did controls.6,8-14 Regrettably, none of these studies presented separate data on BD I and BD II patients; rather, subjects included mixed BDI and BD II patients or only those with BD I. As BD II differs from BD I in genetic,15-17 biological,18 neuropsychological,19 and clinical20-22 aspects, the personality traits of individuals with BD II and BD I should be assessed separately.

Most studies of the specific personality traits of patients with BD have sought to differentiate these patients from normal controls6,7 or to differentiate bipolar from unipolar patients.23-25 In contrast, there are few data comparing personality or temperament between BD I and BD II patients. One study described the distinct temperamental profiles of BD I and BD II patients using various temperament and personality scales, but excluding the NEO-PI.26 We therefore explored the similarities and disparities in personality traits as measured by the NEO-PI between the two subtypes of BD patients.

METHODS

Subjects

This study involved 85 BD I (47 females, 38 males) and 43 BD II (23 females, 20 males) patients, aged 18 to 65 years, who were recruited from the psychiatric department at a university hospital (Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea). Each patient was diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria, based on all available information obtained from unstructured interviews with subjects and family members, and medical records. Diagnosis was confirmed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID).27 We obtained written informed consent from all participants after explaining the aims and procedures of the study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Asan Medical Center.

All patients were in remission from their most recent episode and in a euthymic state. In this study we defined the remission as the subject had not met the criteria of mood episode of DSM-IV for at least 8 weeks prior to study entry determined by psychiatrists who were in charge of treatment. In addition, the subject in remission had not shown prominent work and social impairment during that period. Patients with a primary diagnosis other than BD I and BD II, those with evidence of active substance abuse or dependence when recruiting for the study, and those with clinically diagnosed Axis II personality disorder, were excluded. In addition, individuals with organic brain syndrome, mental retardation, dementia, or inability to complete self-report measures, were excluded. We obtained information about socio-demographic variables considered relevant to personality trait assessments; these included education, Socio-Economic Status (SES),28 and marital status.

Assessment of personality traits

The revised NEO-PI (NEO-PI-R)29 was administered to all subjects. This is a self-reporting measure consisting of 240 items, each rated on a five-point Likert scale, assessing Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness.30 Each of the personality dimensions has six lower-order, correlated facets to measure these narrower dimensions. The NEO-PI-R scale is one of the most widely used measures to assess personality features both in healthy individuals and psychiatric patients. In this study, we used a Korean version of the NEO-PI-R; this version showed adequate reliability and validity in a prior study.31 In this scale, Neuroticism is defined as a predisposition to psychological stress, as manifested by anxiety, anger, depression, or other negative affects; Extraversion includes sociability, liveliness, and cheerfulness; Openness is seen as aesthetic sensitivity, intellectual curiosity, need for variety, and the holding of non-dogmatic attitudes; Agreeableness involves trust, altruism, and sympathy; and Conscientiousness involves a disciplined striving after goals and a strict adherence to principles.29,30 In addition to comparing BD I and BD II patients, we analyzed the results of personality assessment in our patients in comparison with data from a Korean normative sample.31

Statistical analysis

Baseline features of the two BD subtypes were compared using the chi-squared test for categorical data, or t-tests for continuous variables with approximately normal distribution. Scores on the NEO-PI-R were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. A two-tailed alpha level of p=0.05 was used to define statistically significant group comparisons on all measures. Cohen's d effect size32 was calculated for the differences between NEO-PI-R scores of BD I and BD II patients, and normative data, using means and standard deviations for each group. All statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Version 12.0 K except for comparisons with the normative data of NEO-PI-R where Excel 2007 of Microsoft Office was used.

RESULTS

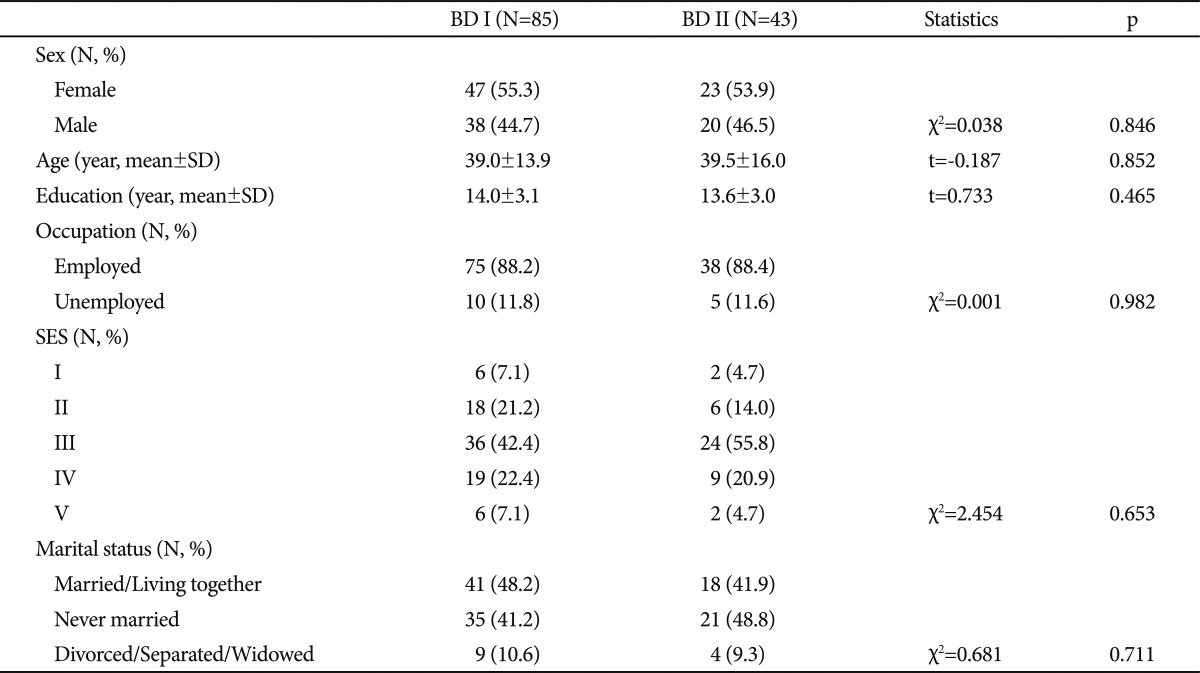

The demographic and clinical characteristics of BD I and BD II patients are summarized in Table 1. The two groups were comparable in gender distribution, age, education, occupation, marital status, and SES.

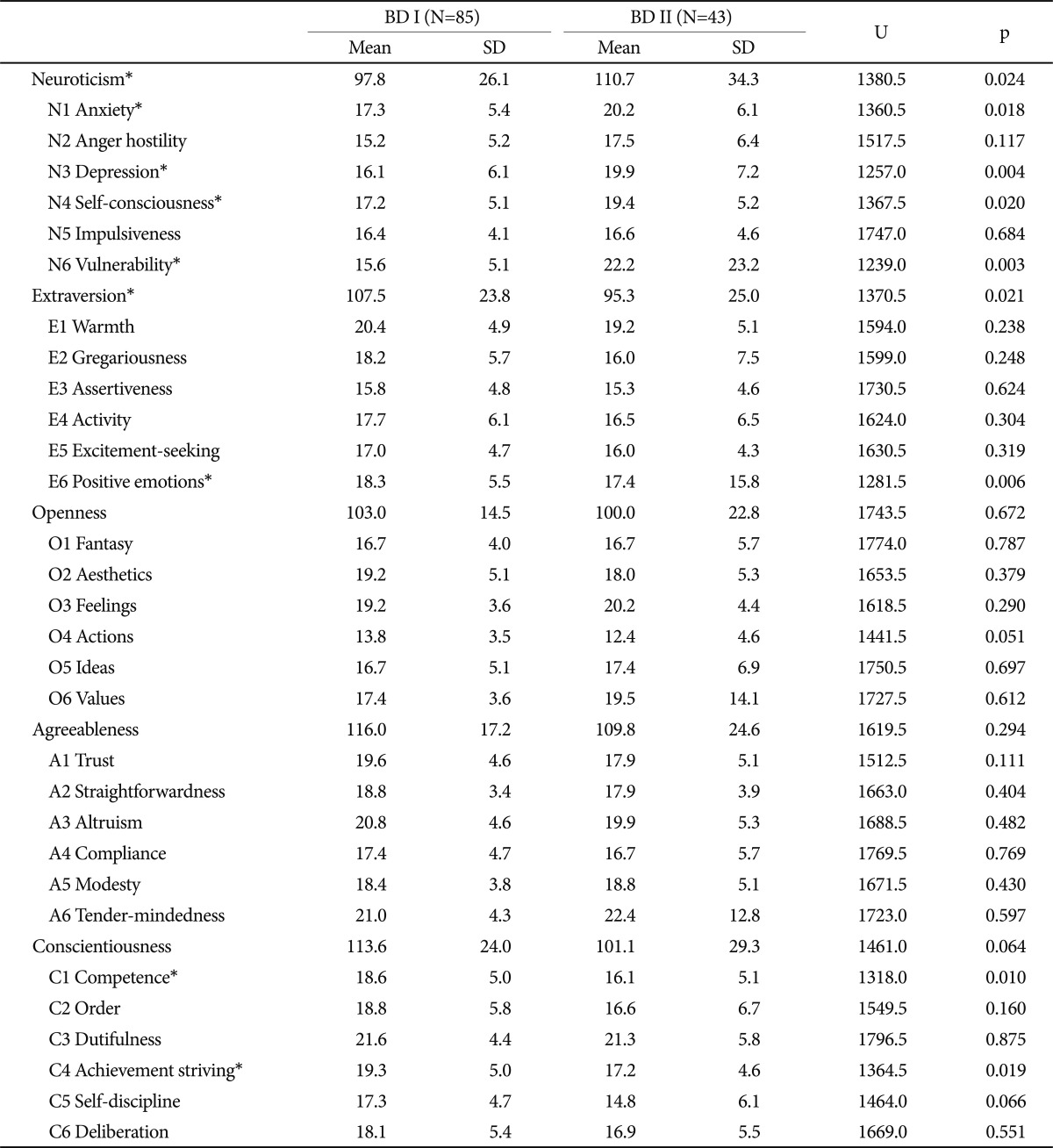

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and tests of significance for BD I and BD II on each of the five dimensions of the NEO-PI-R and the corresponding facets of Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Contentiousness. BD II patients had higher scores than had BD I patients on Neuroticism (110.7±34.3 vs. 97.8±26.1, U=1380.5, p=0.024) and its four corresponding facets: Anxiety (20.2±6.1 vs. 17.3±5.4, U=1360.5, p=0.018), Depression (19.9±7.2 vs.16.1±6.1, U=1257.0, p=0.004), Self-consciousness (19.4±5.2 vs. 17.2±5.1, U=1367.5, p=0.020), and Vulnerability (22.±23.2 vs. 15.6±5.1, U=1239.0, p=0.003). The BD II group scored lowered than the BD I group on Extraversion (107.5±23.8 vs. 95.3±25.0, U=1370.5, p=0.021) and its lower-order facet Positive emotion (18.3±5.5 vs. 17.4±15.8, U=1281.5, p=0.006). In addition, Competence (18.6±5.0 vs. 16.1±5.1, U=1318.0, p=0.010) and Achievement-striving (19.3±5.0 vs. 17.2±4.6, U=1364.5, p=0.019) facets were significantly lower for BD II than for BD I, although the difference in Consciousness, which is the higher-order dimension that includes these two facets, did not attain statistical significance (p=0.064). There were no significant between group-differences on the Openness (p=0.672) and Agreeableness (0.294) dimensions.

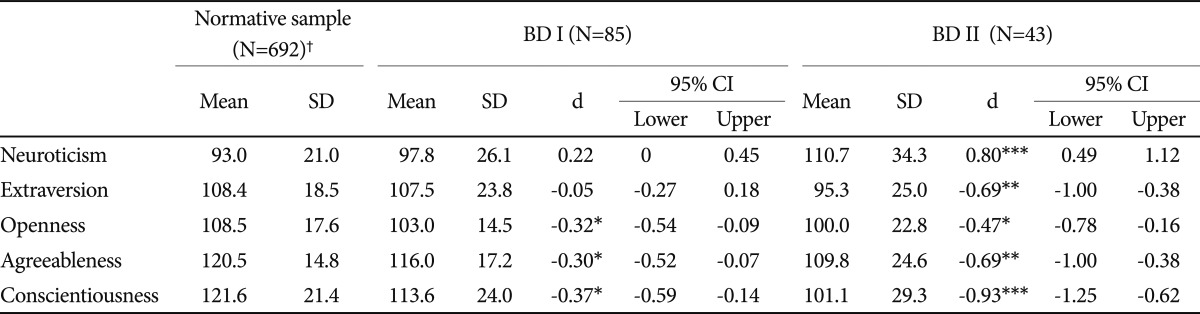

When we compared the NEO-PI-R scores of patients with BD I and normative data (Table 3), we observed small effect sizes for differences in Neuroticism (d=0.22), Openness (d=-0.32), Agreeableness (d=-0.30), and Conscientiousness (d=-0.37). A comparison of scores of patients with BD II with normative data showed large effect sizes for the differences in Neuroticism (d=0.80) and Conscientiousness (d=-0.93), medium effect sizes for the differences in Extraversion (d=-0.69) and Agreeableness (d=-0.69), and a small effect size for Openness (d=-0.47) (Table 3). Thus, in patients with BD II, Neuroticism and Conscientiousness showed greater differences than did other personality dimensions assessed by the NEO-PI-R when compared with normative data; however, relative to BD II, small effect size for differences in Neuroticism and Conscientiousness between the scores of BD I and normative data were observed.

DISCUSSION

One of the key findings of this study was the prominent disparity in the Neuroticism dimension, with BD II patients scoring significantly higher than BD I patients. In addition, scores on the lower-order facets of the Neuroticism dimension, to wit Anxiety, Depression, Self-consciousness, and Vulnerability, differed significantly between the two groups. Akiskal et al.33, in accordance with our finding, have reported that BD II patients had high Neuroticism scores, whereas BD I had low scores on this dimension, although the cited study measured Neuroticism in a manner distinct from the tests used in the present study. Neuroticism is the predisposition to experience psychological stress, as manifest by depression, anxiety, or other negative affect.34 Our results therefore suggest that patients with BD II have greater psychological vulnerability than do patients with BD I, so that stress more easily leads to maladaptive reactions and depression in BD II patients. Neuroticism is well known to be associated with certain clinical features of depression, including greater chronicity and severity, and a higher incidence of recurrence.35-37 As in unipolar depression, it is plausible that higher Neuroticism may have a negative impact on the outcome of BD II; however, this speculation need further evidence to be proved.

We found that BD II patients scored lower than did BD I patients on Extraversion, which is consistent with previous results.33 The lower-order facet of Extraversion, Positive emotion, was also lower in BD II than in BD I patients. Extraversion is associated with the quantity and intensity of energy directed outwards into the social world and encompasses traits such as sociability, activity, and the tendency to experience positive emotions.34 High scores on the Positive emotion facet are related to the experience of joy, happiness, love, excitement, and optimism.34 Based on the FFM description, our results indicate that patients with BD II may be less interested in social activities and have a lower capacity to experience positive affect than patients with BD I. Furthermore, BD II patients are less sociable and more likely to have negative affectivity than BD I based on our finding of the lower Extraversion score of BD II patients.

Achievement-striving striving and Competence facets were also significantly lower for BD II than for BD I patients. Achievement-striving captures the personality trait of need for personal achievement and sense of direction.34 This facet could be conceptualized as an aspect of positive affect regulation.38 A prospective study in BD I patients showed that a high Achievement-striving facet score predicted increases in manic symptoms.39 This facet is regarded as a propensity of BD I rather than BD II patients. Competence measures the tendency to believe in self efficacy.34 A lower sense of competence could make individuals likely to indulge in pessimistic thoughts; thus, the lower score of BD II in these facets may reflect cognitive distortion and/or relatively low self-esteem than BD I.

BD II has been shown to be a categorically different entity than BD I in genetic,15-17 biological,18 neuropsychological,19 and clinical20-22 aspects. Thus, BD II is not likely integrated with BD I at the level of personality traits as well. If the two subtypes of BD exist in a spectrum, they should be much more similar than different in the personality traits measured in our study. However, we found that BD II and BD I patients were strikingly dissimilar on Neuroticism and Extraversion. Although our study design could not fully account for the etiological distinction between BD I and BD II, the distinct personality profiles of these two subtypes may suggest fundamental difference in trait(s) between BD I and BD II patients.

When we compared results in BD II patients with normative data, we found profound deviations in all five dimensions. Differences with large effect sizes were seen for Conscientiousness and Neuroticism, with medium effect sizes for Extraversion and Agreeableness, and a small effect size for Openness. BD I patients, however, showed less deviation from normative data, with small effect sizes for Neuroticism, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. This result is consistent with the notion that most BD I patients are sanguine and describe themselves as near-normal in Extroversion, whereas BD II patients exhibit greater mood instability potentially linked with temperamental dysregulation.33

Our results should, however, be interpreted in the context of methodological limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional design of the present study was unable to determine whether the personality traits measured were premorbid traits or post-affective personality changes. For example, we could not exclude the possibility that the high Neuroticism observed in BD II patients was a pathoplastic consequence of the bipolar illness. That is, recurrent affective episodes might cause negative social, occupational, or economic consequences; thus patients with BD may be more likely to show high Neuroticism as the number of episodes increases. Further work with longitudinal observation is required to address this issue. In addition to the effect of preceding affective episodes on personality, residual depressive and/or hypomanic symptoms might also have influenced the measurement of personality traits. In the present study, we excluded patients who were not in remission from discrete affective episode to control for the effect of residual affective symptoms. However, this did not mean that our study subjects were completely free from any level of subthreshold affective symptoms, although diagnostically they had remitted from major affective episodes.

In addition, the effect of comorbid diagnoses, personality problems, or other relevant clinical characteristics may have affected the measurement of personality traits. Although we excluded patients with active other primary Axis I disorders except BD, some patients may have had pre-existing psychiatric symptom(s) that were not clinically recognized or screened out during the structured interview. In addition, it is the limitation of our study design that we did not adapt the measure coexisting anxiety symptoms which could influence on the personality assessment, in particular on Neuroticism. With regard to Axis II disorder comorbidities, we did not adapt the structured interview to detect personality disorders; rather, patients with clinically-diagnosed Axis II disorders were excluded from the study. Since the vast majority of studies on Axis II comorbidities did not differentiate between BD I and BD II patients,40-42 it is less likely that co-existing Axis II disorders account for the differences in personality traits found in the two subtypes. Thirdly, our use of a limited sample size may have impeded our ability to detect substantial but subtle differences in personality traits between the two BD subtypes. Lastly, our study results may not be generally applicable, in that our subjects were recruited from one specific tertiary hospital and thus may not be representative of BD patients in general.

In summary, our results clearly suggest that BD I and BD II patients have distinct personality which supports the separation in enduring trait dimensions between the two subtypes. The most evident differences were on measures of Neuroticism and Extraversion between BD I and BD II patients from the FFM perspective. Further studies, including longitudinal assessments, are needed to determine how these personality traits are differentially linked with the etiology and clinical expressions of BD I and BD II respectively.