Relationship between Personality and Insomnia in Panic Disorder Patients

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Panic disorder (PD) is frequently comorbid with insomnia, which could exacerbate panic symptoms and contribute to PD relapse. Research has suggested that characteristics are implicated in both PD and insomnia. However, there are no reports examining whether temperament and character affect insomnia in PD. Thus, we examined the relationship between insomnia and personality characteristics in PD patients.

Methods

Participants were 101 patients, recruited from 6 university hospitals in Korea, who met the DSM-IV-TR criteria for PD. We assessed sleep outcomes using the sleep items of 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17)(item 4=onset latency, item 5=middle awakening, and item 6=early awakening) and used the Cloninger's Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised-Short to assess personality characteristics. To examine the relationship between personality and insomnia, we used analysis of variance with age, sex, and severity of depression (total HAMD scores minus sum of the three sleep items) as the covariates.

Results

There were no statistical differences (p>0.1) in demographic and clinical data between patients with and without insomnia. Initial insomnia (delayed sleep onset) correlated to a high score on the temperamental dimension of novelty seeking 3 (NS3)(F1,96=6.93, p=0.03). There were no statistical differences (p>0.1) in NS3 between patients with and without middle or terminal insomnia.

Conclusion

The present study suggests that higher NS3 is related to the development of initial insomnia in PD and that temperament and character should be considered when assessing sleep problems in PD patients.

INTRODUCTION

Panic disorder (PD), one of the quite common anxiety disorders, is often a disabling, chronic illness.1,2 PD is frequently comorbid with insomnia, which could exacerbate panic symptoms and contribute to relapse of PD.3 The association between insomnia and anxiety disorders, such as general anxiety disorder, post-traumatic syndrome disorder and PD,4-6 has been showed in many researches. Several researches showed that insomnia is more commonly reported in those with PD than in normal individuals,7 and impaired sleep initiation and maintenance has been confirmed by polysomnographic studies.8 In addition, recurrent sleep panic attacks can create a state of anticipatory anxiety and apprehension over the prospect of yet another night of sleeplessness followed by another day of fatigue.9,10 The prevalence of insomnia in PD patients has been reported about 68 percent up to 93 percent6 possibly because of anxiety, depression11 and nocturnal panic attack.6

PD is frequently accompanied by agoraphobia and panic patients with agoraphobia are known to have a poorer prognosis, compared with those without agoraphobia. There had been few reports about the difference in the prevalence of insomnia between PD with agoraphobia and PD without agoraphobia.12,13

Insomnia can be caused by biological, psychological, and environmental predisposing factors and is known to also be affected by personality traits.14 However, the exact mechanism of insomnia in PD is still unknown. Researches have shown that both temperament and character are implicated in PD,15 and some studies also suggest a close relationship between certain, specific personality traits and insomnia.15-18 In addition to, several studies showed that personality disorders were implicated in PD.19-21 Personality disorders are common in subjects with PD and personality disorders have been shown to affect the course of PD.22 The prevalence and the effect on insomnia of personality disorders in PD patients are not well known till now.

Cloninger's personality theory14 provides an integrated concept for explaining psychopathology of PD, as well as that of insomnia. This model conceptualized personality as having 4 temperament dimensions [novelty seeking (NS), harm avoidance (HA), reward dependence (RD) and persistence (P)] and three character dimensions [self-directedness (SD), cooperativeness (C), and self-transcendence (ST)]. HA is known to play a crucial role in development and treatment outcome of PD.15,23 Hypothetically, each temperament and character di-mension is linked to a specific neurotransmitter system and genetic basis.24,25 For instance, researches have shown that the dopamine receptor genetic polymorphism connects to NS,26-29 whereas serotonin transporter promoter genetic polymorphism relates to HA.30,31 In addition, RD may link to the norepinephrine system.32

Researches suggest susceptibility to developing insomnia related to some personality traits,17,18 although the idea that all insomniacs have specific personality traits is still controversial. Recently, de Saint Hilaire reported that insomniac patients showed higher HA compared to control subjects.33

However, no reports have examined the relationship between personality and insomnia in PD or whether insomniac PD patients show different personality characteristics from those without insomnia. This study aimed to compare tempera-ment and character between insomniacs and non-insomniacs among panic patients.

METHODS

Subjects

Participants were 101 patients (58 men and 43 women; aged 41.5±10.0 years), recruited from 6 university hospitals in Korea, who met the DSM-IV-TR criteria for PD as determined by structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID).34 We excluded patients who satisfied the DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depression or had a lifetime history of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or eating disorder; a history of alcohol or drug abuse or dependence; or a major medical illness. All patients took no medication for at least 2 weeks before participating in the study (or 5 weeks, in the case of fluoxetine). After receiving a complete description of the study, all participants gave written informed consent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Samsung Medical Center.

Measures

We used the Cloninger's Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised-Short (TCI-RS)35 to assess personality characteristics and also administered the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS),36 the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A),37 and 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17)38 to all participants. For this study, we defined insomniac patients as those who had score of more than zero on the HAMD-17 sleep item 4 (sleep onset latency), 5 (middle awakening), or 6 (early awakening), whereas non-insomniac patients were defined as those who had only zero score on all three sleep items. We classified insomniacs as three groups; initial, middle and terminal insomnia groups. Regardless of the gr-oup overlapping, PD patients who had score of more than zero on item 4, 5 and 6 were defined as initial, middle and terminal insomniacs, respectively.

Statistical analyses

We used the Student's t-test to determine differences between insomniac and non-insomniac panic patients in demographic and clinical characteristics and employed analysis of variance39 to examine the relationship between personality and insomnia, controlling for age, sex, and severity of depression (it was defined as total HAMD-17 score minus the sum score of HAMD-17 item 4, 5, and 6) as covariates. The differences in insomnia profiles and personality characteristics between PD with and without agoraphobia were also examined using the Student's t-test. To perform all statistical tests, we used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 17.0 (SP-SS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and we accepted statistical significance for p-values of <0.017 (0.05/3), by Bonferroni correction.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

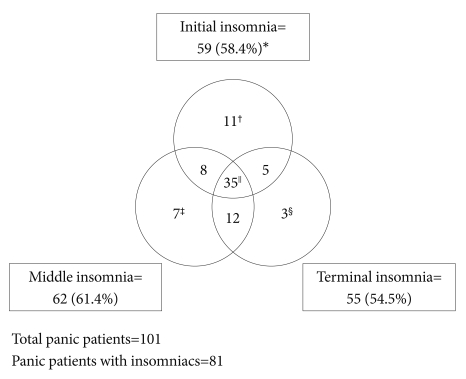

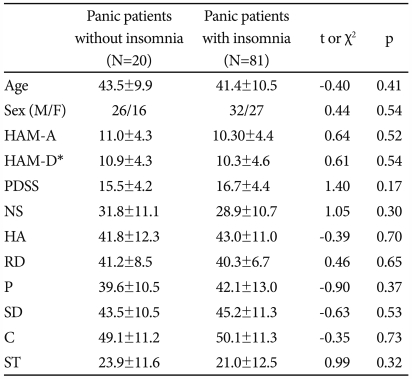

Table 1 shows the participants characteristics. Of the 101 panic patients, 20 (19.8%) panic patients had no insomnia in terms of the HAMD-17 sleep items whereas 81 (80.2%) panic patients had insomnia. We compared characteristics of panic patients with and without insomnia. There were no significant differences in age, sex, HAM-A score, HAM-D score (to-tal HAMD-17 score minus sum score of item 4-6 to assess the severity of depression) and PDSS score between PD patients with and without insomnia (all p-values >0.1)(Table 1). Among 101 panic patients, eighty-one patients had any sorts of insomnia. Fifty nine patients (58.4%) showed initial insomnia, whereas 62 (61.4%) and 55 (54.5%) patients showed middle and terminal insomnia, respectively. Patients who have both initial and middle insomnia were 43 (42.6%), patients who have both initial and terminal insomnia were 40 (39.6%), patients who have both middle and terminal insomnia were 47 (46.5%), and patients who have all of initial, middle and terminal insomnia were 35 (34.7%)(Figure 1).

Comparison of demographic and psychological data between panic disorder patients with and without insomnia

Agoraphobia

There were no significant differences in the TCI variables and prevalence of initial, middle and terminal insomnia between PD patients with and without agoraphobia (all p-values >0.1).

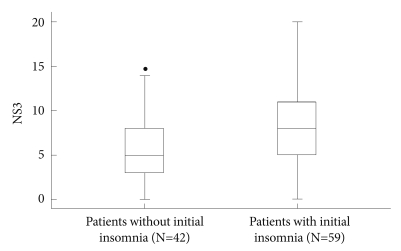

Insomnia and personality

Initial insomnia (delayed sleep onset) correlated significantly to high scores in the temperamental dimension of NS3 (F1,96=6.93, p=0.03) NS1, NS2 and NS4 did not show any significance in relation with initial insomnia. ANOVA revealed that low SD score related to initial insomnia (F1,99=4.2, p=0.04), but the significance disappeared after controlling age, sex, HAM-A score, severity of depression and PDSS score (p=0.1). Figure 2 shows the relation between initial insomnia and NS3.

Comparison of novelty-seeking 3 between panic disorder patients with and without initial insomnia (F1,96=6.93 , Bonferroni corrected p=0.03 using analysis of variance controlling for age, sex, HAM-A, HAM-D* and PDSS score). *total sum of HAMD-17 scores excluding sleep items (4, 5, and 6). NS 3: novelty seeking 3, HAM-A: Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety, HAM-D: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, PDSS: Panic Disorder Severity Scale.

There were no significant (p>0.1) differences in other temperament and character dimensions including NS, HA, RD and P and SD, C, ST, in case of middle and terminal insomnia with controlling age, sex, HAM-A score, severity of depression and PDSS score.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found that NS3 is related to the development of initial insomnia in panic patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare personality characteristics between panic patients with and without insomnia.

Up to date, many studies have suggested specific personality traits are implicated in insomnia.17,18 In addition to, several studies showed that personality disorders were also common in PD19-21 and comorbid personality disorders in PD affect the course and outcome of PD.22,40 However, the prevalence and the effect on insomnia of personality disorders in PD patients are not well known.

Cloninger's personality theory14 provides an integrated concept for explaining psychopathology of PD, as well as that of insomnia. Many insomniacs have signs of neuroticism, internalization, anxious concerns, and personality traits associated with perfectionism3,41 and those characteristics are closely related to HA in the Cloninger's psychobiosocial model.35 HA is characterized by excessive worrying, pessimism, shyness, being fearful and doubtful, and being easily fatigued. Also, biological studies have shown that some genetic polymorphisms in the serotonergic system correlate to HA, as well as to insomnia.42,43 Thus, we initially hypothesized that HA would also play an important role in the development of insomnia in the panic patients. However, unexpectedly, our results show that HA is not related to the development of insomnia in PD patients, whereas high NS3 is related to initial insomnia in PD patients.

NS, which has been suggested to be linked to the dopamine system,27,29 reflects the tendency towards exploratory activities, lack of inhibition, and impulsiveness.44 Thus, individuals with high NS tend to be quick-tempered and more excitable, exploratory, curious, enthusiastic, ardent, easily bored, impulsive, and disorderly.44 Although it is unclear why high NS3 is linked to initial insomnia in PD, some hypotheses might possibly explain this finding. Researchers know that the dopaminergic system is connected to the sleep-wake cycle. Wang et al.45 reported a correlation between impulsivity scores and mismatch negativity (MMN) in insomniacs,45 which suggests a link between the impulsive trait and the arousal mechanism in primary insomnia. Thus, high NS may play a role in the development of initial insomnia in PD via aberrant dopaminergic function. In addition, people with high NS may have unhealthy, irregular lifestyles,46,47 which could act as a mediating factor in the development of insomnia in panic patients. Lifestyle is well-known for playing an important role in the development of both PD and insomnia. Further studies to examine this hypothesis will be needed.48-50

Agoraphobia is known to be one of the important prognostic factors in PD. In this study, agoraphobia does not affect either insomnia or personality in PD patients, and we suggest that the relationship between insomnia and personality in PD is a unique phenomenon regardless of agoraphobia.

As similar with previous researches, our study showed the prevalence rate of 80.2% of insomnia in PD patients. The prevalence of insomnia in PD patients has been reported about sixty-eight percent up to ninety-three percent,6 possibly because of anxiety, depression11 and nocturnal panic attack.6 Stein et al.7 reported high prevalence rate of insomnia in patients with PD. At that study, sixty-eight percent among PD patients was reported to have moderate or severe sleep problem compared to only fifteen percent of healthy control. Overbeek et al.51 also reported higher prevalence of sleep complaints in PD patients than normal population. There had been a few reports about the difference in the prevalence of insomnia between PD with agoraphobia and PD without agoraphobia.12,13 However, any reports did not specify the prevalence of insomnia in PD patients with agoraphobia.

This study had several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small for generalizing the results to PD. Second, we did not have any healthy controls in this study. Third, we did not measure some important psychosocial variables affecting the course of PD, such as socio-economic status, employment, education, and the consumption of alcoholic beverages and caffeine. Lastly, we did not utilize any specific sleep measures other than sleep items on HAMD-17 and thus might not accurately assess the PD patients' sleep problems. We should have used other sleep questionnaires and polysomnography to specify sleep problems including sleep structure and stages. However, this study is the first attempt to examine the relationship between sleep problems and personality characteristics in PD. Further studies correcting these limitations are needed.

The present study suggests that higher score of NS3 is related to the development of initial insomnia in PD. The clinicians should consider temperament and character when assessing sleep problems in PD.