Reconsidering Clinical Staging Model: A Case of Genetic High Risk for Schizophrenia

Article information

Abstract

The clinical staging model is considered a useful and practical method not only in dealing with the early stage of psychosis overcoming the debate about diagnostic boundaries but also in emerging mood disorder. However, its one limitation is that it cannot discriminate the heterogeneity of individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis, but lumps them all together. Even a healthy offspring of schizophrenia can eventually show clinical symptoms and progress to schizophrenia under the influence of genetic vulnerability and environmental stress even after the peak age of onset of schizophrenia. Therefore, individuals with genetic liability of schizophrenia may require a more intensive intervention than recommended by the staging model based on current clinical status.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades since its introduction, the concept of ultra-high risk, clinical-high risk or at-risk mental state for psychosis has been propagated and it is now known that there are numerous biological alterations even prior to the onset of psychosis.1 The clinical-high risk state for schizophrenia, compared with genetic-high risk state, was regarded as a more efficient and appropriate strategy for the observation of the neural correlates of psychotic breakdown.2 However, is the heterogeneity of the individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis is manifest in the fact that the majority of them exhibit a range of psychiatric outcomes other than transition to psychosis. Thus the diagnosis and treatment for this population provoked debates about the unnecessary stigmatization and side effects.

McGorry et al.3 proposed a heuristic concept of ‘clinical staging model’ for the diagnosis and intervention of early psychosis. This framework is considered a useful and practical method not only in dealing with the early stage of psychosis overcoming the debate about diagnostic boundaries but also in emerging mood disorder.45 It is regarded that an early intervention focus should be given to the broad range of psychiatric syndromes that may be more profitable rather than focus only on ultra-high risk syndrome.6 However, its one limitation is that it cannot discriminate the heterogeneity of individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis, but lumps them all together. Therefore, we would like to suggest one more point for consideration through the following case.

CASE

Patient A, a 34-year-old single male, was recruited as a case of genetic high risk for schizophrenia 11 years ago, and underwent yearly follow-up evaluation. In his family pedigree, both of his parents had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, as well as one of his uncles. He had been suffering from bizarre psychotic behaviors and inappropriate rearing of the both parents from childhood. While he had not been quite interested in interpersonal relationship or academic achievement, he did not show any clinical symptoms at the time of baseline assessment. A diagnosis of schizoid personality disorder was given. Until 3 years of followed up, despite of stress from his parents' disease and his mother's death, he was free of psychiatric symptoms and at good functional status. He no more felt the need to participate in the follow-up program and he refused follow-up assessments afterwards. Thus, from 2008 till 2011, he had been lost to follow-up, although later retrospective assessment strongly suggested the presence of sustained distress during this period. In Jul 2012, he wanted psychiatric counseling for depressive mood, anger, and communication problem. However, his symptoms were very mild and he was still functioning well in his life. Although there were some psychiatric symptoms, he did not meet the criteria for ultra-high risk for psychosis. In Dec 2013, after 9 years of follow-up, attenuated psychotic symptoms such as idea of reference, suspiciousness occurred, the severity fulfilling the ultra-high risk for psychosis. He was diagnosed as both genetic risk and deterioration and attenuated psychotic symptoms syndrome of ultra-high risk for psychosis and also as depressive disorder not otherwise specified. We tried intensive cognitive behavioral therapy and supportive psychotherapy but his compliance was poor. In Jul 2014, he showed persecutory delusion with a high level of conviction and his transition to a psychotic disorder was suspected. Disorganized speech and negative symptoms were also observed. We assessed him as a case of transition to schizophrenia and atypical antipsychotic medication was prescribed. In Dec 2015, a11-year follow-up as a GHR individual and 2-year follow-up as a CHR individual and 1.5 year after onset of schizophrenia, his psychotic symptoms were quite alleviated but general functioning has not yet improved sufficiently.

DISCUSSION

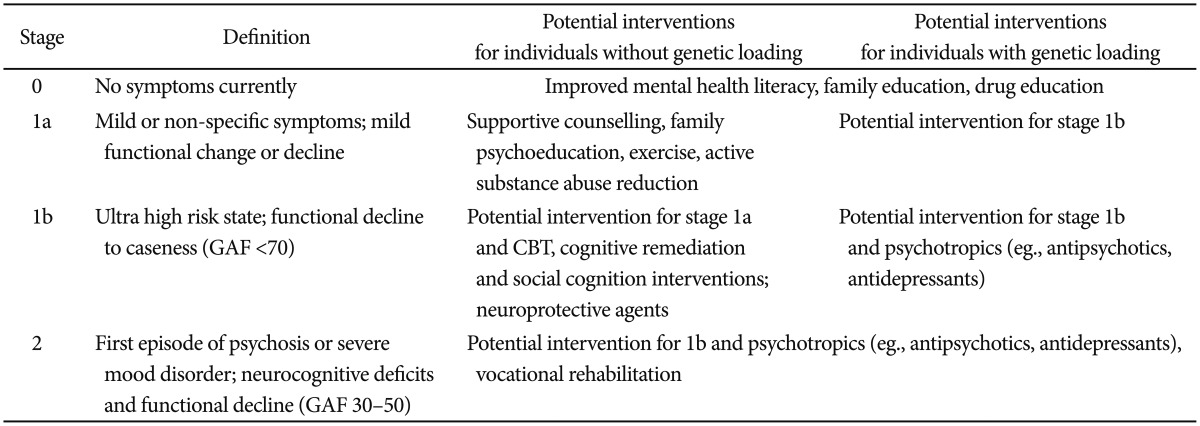

This case suggests that even a healthy offspring of schizophrenia can eventually show clinical symptoms and progress to schizophrenia under the influence of genetic vulnerability and environmental stress even after the peak age of onset of schizophrenia. In the clinical staging model, mild or non-specific symptoms of psychosis or severe mood disorder, mild functional change or decline in teenage population is considered as stage 1a (Table 1). It is recommended that the family psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy should be given to the population in stage 1a. However, classifying the people at genetic high risk as being at the same level of risk with those with similar symptoms but without genetic risk, might not be appropriate in the prediction of their further clinical course. Counting those with stage 1a symptoms and genetic vulnerability as equivalent of stage 1b and providing them with a more active treatment might offer a chance to reduce the possibility of symptoms exaggeration. Likewise, counting those with stage 1b symptoms and genetic vulnerability as equivalent of stage 2 and providing them with a more active treatment including pharmacotherapy might offer a chance to reduce the possibility of their transition to psychosis. It has to be emphasized that treatments, either pharmacological or psychological, must be appropriate for the stage of the disease, since the untimely application of treatment protocols which are inappropriate to the stage of the disease may lead to sub-optimal outcomes, and even to iatrogenic harm.8

Previous studies showed that a family history of psychosis is a significant predictor of the transition to psychosis in CHR individuals.9 Furthermore, the mixed groups containing to two or more subgroups of ‘Genetic Risk and Deterioration State (GRD)’, ‘Attenuated Positive Symptom State (APS)’ and ‘Brief Intermittent Psychotic State (BIPS)’ subgroups showed a higher hazard ratio compared with that of the APS subgroup alone.10 Although, we do not always assume that the mixed group is composed of GRD and APS, this suggests that the CHR individuals with a family history of psychosis may have more vulnerability to psychosis than those without a family history of psychosis. Therefore, individuals with genetic liability of schizophrenia may require a more intensive intervention than recommended by the staging model based on current clinical status.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participant for his time and effort. Written informed consent form was obtained from the participant after the procedures had been fully explained. We specially thank the research coordinators including Min Hee Lee, Hyun Ah Kim. This study was supported by the 2015 Research Fund of the Korean Society for Schizophrenia Research.