Factor Structure and Validation of the Revised Suicide Crisis Inventory in a Korean Population

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Because of the exceptionally high suicide rates in South Korea, new assessment methods are needed to improve suicide prevention. The current study aims to validate the revised Suicide Crisis Inventory-2 (SCI-2), a self-report measure that assesses a cognitiveaffective pre-suicidal state in a Korean sample.

Methods

With data from 1,061 community adults in South Korea, confirmatory factor analyses were first conducted to test the proposed one-factor and five-factor structures of the SCI-2. Also, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to examine possible alternative factor structure of the inventory.

Results

The one-factor model of the SCI-2 resulted in good model fit and similarly, the five-factor model also exhibited strong fit. Comparing the two models, the five-factor was evaluated as the superior model fit. An alternative 4-factor model derived from EFA exhibited a comparable model fit. The Korean version of the SCI-2 had high internal consistency and strong concurrent validity in relation to symptoms of suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety.

Conclusion

The SCI-2 is an appropriate and a valid tool for measuring one’s proximity to imminent suicide risk. However, the exact factor structure of the SCI-2 may be culture-sensitive and warrants further study.

INTRODUCTION

Predicting who, when, and how an individual will attempt suicide is challenging even for suicide researchers and clinicians [1]. This is because suicidal ideation (SI) oscillates [2] and the desire to act on those thoughts can appear rapidly and unpredictably [3,4]. One of the most common methods that has long been used to evaluate suicide risk has been by directly assessing thoughts of death or suicide [5]. Although these assessments can provide valuable clinical information [6], previous studies have highlighted high rates of nondisclosure of SI [7,8], resulting in clinicians missing many individuals in need of care. Indeed, a significant number of suicide decedents denied SI or intent to healthcare providers prior to their deaths [9,10]. As such, reliance on SI in assessing suicide risk does not seem optimal, and instead novel tools that identify individuals at imminent risk for suicide should be implemented [1,11,12].

One such approach is to assess the Suicide Crisis Syndrome (SCS), which is thought to emerge proximate to imminent suicide risk. The syndrome was developed based on empirical predictors of imminent risk for suicidal behaviors and includes cognitive and affective characteristics that potentially precede a suicide attempt. Specifically, the SCS comprises five components and is divided into two criteria: criterion A, frantic hopelessness/entrapment; and criterion B, which includes four symptom domains, affective disturbance, loss of cognitive control, hyperarousal, and social withdrawal [13,14]. A chief difference between the SCS and contemporary suicide risk assessments is that it does not rely on self-reports of SI that are often known to be significantly biased [2,15]. Together, the SCS is posited to be a unidimensional diagnosis of one’s near-term suicidal mental state [16].

Frantic hopelessness/entrapment, identified as one of the central predictors of suicidal behavior [17,18] as well as a core feature of other models of suicide (e.g., the integrated motivational-volitional model) [19], is characterized by feelings of hopelessness, defeat, and the perception that death is the only alternative because life adversities seem inescapable [20]. Feelings of entrapment can be experienced as a result of external (e.g., relationship problems) and internal (e.g., inner thoughts of defeat) circumstances that prompt one’s desire to escape their current state [21]. Frantic hopelessness/entrapment is thought to be the core symptom of the SCS.

Criterion B includes affective disturbances, loss of cognitive control, hyperarousal, and social withdrawal. Affective disturbance incorporates four features: emotional pain [22], rapid spikes of negative emotions [23], extreme anxiety [24,25], and acute anhedonia [26]. Loss of cognitive control includes rumination [13], cognitive rigidity [27], ruminative flooding [25], and failed thoughts suppression [28,29]. Hyperarousal includes components of agitation [24,30], hypervigilance, irritability [31-34], and insomnia [35-37]. Hyperarousal, especially the association between hyperarousal symptoms and suicide attempts, has especially been noted among military service members with posttraumatic stress disorder where they are continuously wary and on edge about external events that may be of threat to them [38]. Finally, social withdrawal reflects individuals’ interactions and feelings of connectedness with the environment surrounding them [39,40]. Each of the aforementioned factors has been linked to suicidal thoughts and/or behaviors.

The SCS is assessed using the Suicide Crisis Inventory-2 (SCI-2), a 61-item self-report assessment, which is the revised version of the former Suicide Crisis Inventory [12]. The psychometric properties of the inventory have been supported across multiple studies showing strong reliability, validity and internal consistency [41,42]. One- and five-factor structures have been identified as strong model fits [41]; hence, it is necessary to examine and confirm the reliability of the identified factor structures and whether they are applicable in different cultures. Clinical utility and predictive validity among high-risk population have also been supported where both inpatient and outpatient populations who fulfilled the complete criteria of the SCS were more likely to attempt suicide in the near future compared to those who met partial criteria [16,43,44]. Validating SCI-2 in Korean would aid implementation of near-term suicide risk assessment even without clear disclosure of SI [11].

The present study sought to 1) translate the SCI-2 into Korean and validate it in a Korean sample, 2) evaluate the factor structure and the psychometric properties of the SCI-2 through confirmation of previously identified structures and exploration of alternative possibilities, 3) examine the internal consistency and reliability of the SCI-2, and 4) inspect its concurrent validity with measures of SI, depression symptoms, and anxiety symptoms. We hypothesized that the Korean version of the SCI-2 would support both the one-factor and five-factor structures as outlined by the original version of the scale. No a priori hypotheses were made regarding alternative structures, given that these analyses were intended to be exploratory. We also predicted that there will be strong correlations between factors as it is measuring cognitive and affective elements that are known to predict suicidal behaviors, and that the SCI-2 would exhibit concurrent validity with measures of depression, anxiety, and SI.

METHODS

Participants and procedures

This study was conducted as part of a larger international collaborative research project examining suicide during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. All study procedures were approved by the Chungbuk National University Institutional Review Board (CBNU-202007-HR-0120). Korean participants who were 19 years or older and were residing in South Korea during the outbreak of the pandemic were recruited to complete an online Qualtrics survey between August 2020 and October 2020. The survey was dispersed to various sites on social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, University websites). Individuals who were interested in participating in the study signed an online consent form before starting the survey. To ensure participant safety, national mental health and suicide prevention resources were provided during the survey. Participants who fully completed the survey were compensated with a gift card worth 3,000 KRW (approximately 3 dollars).

Measures

SCI-2

The SCI-2 [41] is a 61-item self-report measure that assesses the severity of the SCS over the past several days. Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), and evaluate feelings of entrapment, levels of affective disturbance, loss of cognitive control, hyperarousal, and social withdrawal. The SCI-2 had excellent internal consistency (α=0.97) as well as strong concurrent validity in previous research [41].

Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale screener

The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) screener is a validated 6-item self-report measure that evaluates the severity of SI and suicidal acts [45]. With response options yes or no, 5 items regarding SI were used for this study, anchored to both the past month and lifetime; the highest score was used to reflect participants’ lifetime and past-month severity of SI, with higher scores reflecting more severe SI. In addition to the C-SSRS screener, items asking lifetime suicide attempt (i.e., Have you ever attempted suicide/tried to kill yourself?) and suicide attempt in the past month (i.e., Have you attempted suicide/tried to kill yourself in the past month?) were included. Reliability and validity of the scale has been demonstrated in multiple studies and diverse populations [45,46], including a Korean sample [47].

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a 9-item self-administered assessment that evaluates the severity of depression during the past two weeks [48]. The questionnaire is evaluated on a 4-point Likert scale with total scores ranging from 0 to 27: 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half the days), and 3 (nearly every day). The Korean version of the PHQ-9 had good reliability, validity and internal consistency (α=0.95) [49].

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) is a 7-item self-report scale that measures severity of generalized anxiety disorder [50]. Participants reported the frequency of anxiety symptoms they experienced during the past two weeks with the response options 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half the days), and 3 (nearly every day). Total score ranges from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicative of more severe generalized anxiety symptoms. The GAD-7 had good psychometric properties in a Korean population with an internal consistency of α=0.93 [51].

Translation of the SCI-2

Standard procedures were followed in the process of translating the English version of the SCI-2 into Korean [52]. The inventory was first translated into Korean by a doctoral-level psychologist and a graduate student in clinical psychology. A professional translator was then hired to back translate the items into English, its original language. Dr. Igor Galynker, the author of the inventory, reviewed the back translations to see whether items relevantly reflected their original ones. After making necessary modifications, the authors of the current study revised the entirety of the inventory until the Korean version of it was deemed acceptable. Finally, graduate students in clinical psychology participated in the pilot-testing process of the translated questionnaire. Students reported phrases or words that were difficult to understand, which were changed if consensus of word choice was met.

Data analytic strategy

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy [53] and Bartlett’s test of sphericity [54] were used to establish that these data were suitable for factor analyses. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted to test the proposed one- and five-factor structures of the SCI-2. Specifically, in the one-factor model, all items were set to load onto a single factor. In the five-factor model, items were set to load on their respective subscale factors of the original SCI-2: frantic hopelessness/entrapment, affective disturbance, loss of cognitive control, hyperarousal, and social withdrawal. Because items were ordinal (i.e., rated on a 5-point Likert scale), diagonally weighted least squares estimation was used.

The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the 61 items in the English version of the SCI-2 with direct oblimin rotation, was then conducted on a randomly selected half of the full sample (n=530). Items that significantly loaded onto factors with loadings ≥0.45 were retained. Although 0.40 is a frequently employed standard, we decided to retain items ≥0.45 to diminish cross-loadings and remove items that were weakly associated with their respective factors [55,56]. Items with significant loadings on multiple factors (with factor loadings ≥0.35) were removed from the scale to maintain a simpler factor structure with minimal cross-loadings. The number of suitable factors for the Korean version of the SCI-2 was determined through examination of model fit via the chi-square difference test, balanced with examination of significant loadings across models to establish which model resulted in interpretable factors. Next, CFAs of the remaining items were conducted in the other half of the full sample (n=531) to test the best fitting model yielded from the EFA. Items were set to load on their respective factors yielded from the EFA.

Model fit was evaluated using recommended guidelines [57], including the chi-square statistic (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean residual (SRMR). Namely, good model fit was indicated by a non-significant χ2 statistic, CFI ≥0.95, TLI ≥0.95, RMSEA ≤0.08, and SRMR ≤0.08. Comparison of the one- and five-factor models was computed using the chi-square difference test; however, because the four-factor model yielded from EFA had a different number of items and cases, model comparison was not feasible.

Cronbach’s alpha values were evaluated to establish internal consistency of the scale, while correlation analyses were conducted to examine the scale’s concurrent validity. There were no missing data, as only participants who completed the full study were included in the dataset. Analyses were conducted using psych packages in R, specifically the lavaan [58], semTools [59] packages for CFA analyses, MPlus for EFA analyses (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA), and SPSS Version 27.0 for internal consistency/validity analyses (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Preliminary results

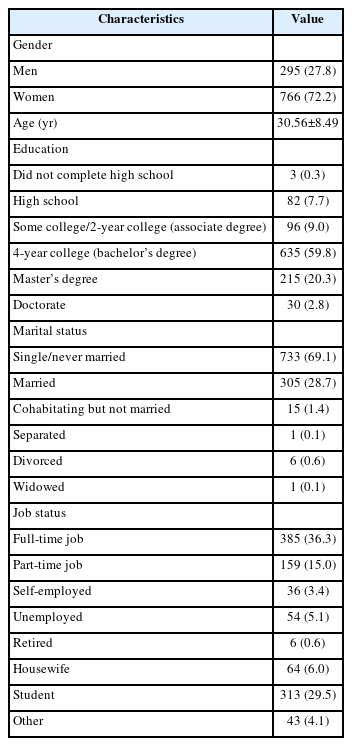

In total, 1,061 participants completed the online Qualtrics survey where 72.2% (n=766) were women and 27.8% (n=295) were men. Ages ranged from 19 to 68 years (30.56±8.49). A majority of the participants were single (69.1%) and had completed their bachelor’s degree (59.8%). Among participants, 29.5% were students, 36.3% had a full-time job, and 5.1% were unemployed. Demographic information of the sample is presented in Table 1. A total of 189 participants (17.8%) had endorsed thoughts of suicide sometime during their life, 405 participants in the past month (38.2%), 67 participants (6.4%) had a history of suicide attempt and among them, 8 participants (11.9%) made an attempt in the past month. Approximately 13.2% were receiving treatment for mental health (e.g., outpatient therapy, group therapy, and medication).

One-factor and five-factor models

CFA

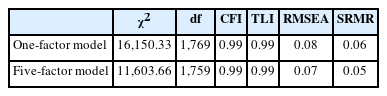

Results of the one-factor CFA of the Korean version of the SCI-2 resulted in good model fit (χ2[1769]=16150.33, p< 0.001, CFI=0.99, TLI=0.99, RMSEA=0.08, SRMR=0.06). Similarly, the five-factor CFA demonstrated strong model fit (χ2[1759]=11603.66, p<0.001, CFI=0.99, TLI=0.99, RMSEA=0.07, SRMR=0.05). Comparison of the one-factor and fivefactor models indicated that the five-factor model demonstrated superior model fit to the one-factor model (Δχ2[10]=4546.67, p<0.001). The results of CFA are presented in Table 2.

Exploration of alternative factor structures

EFA

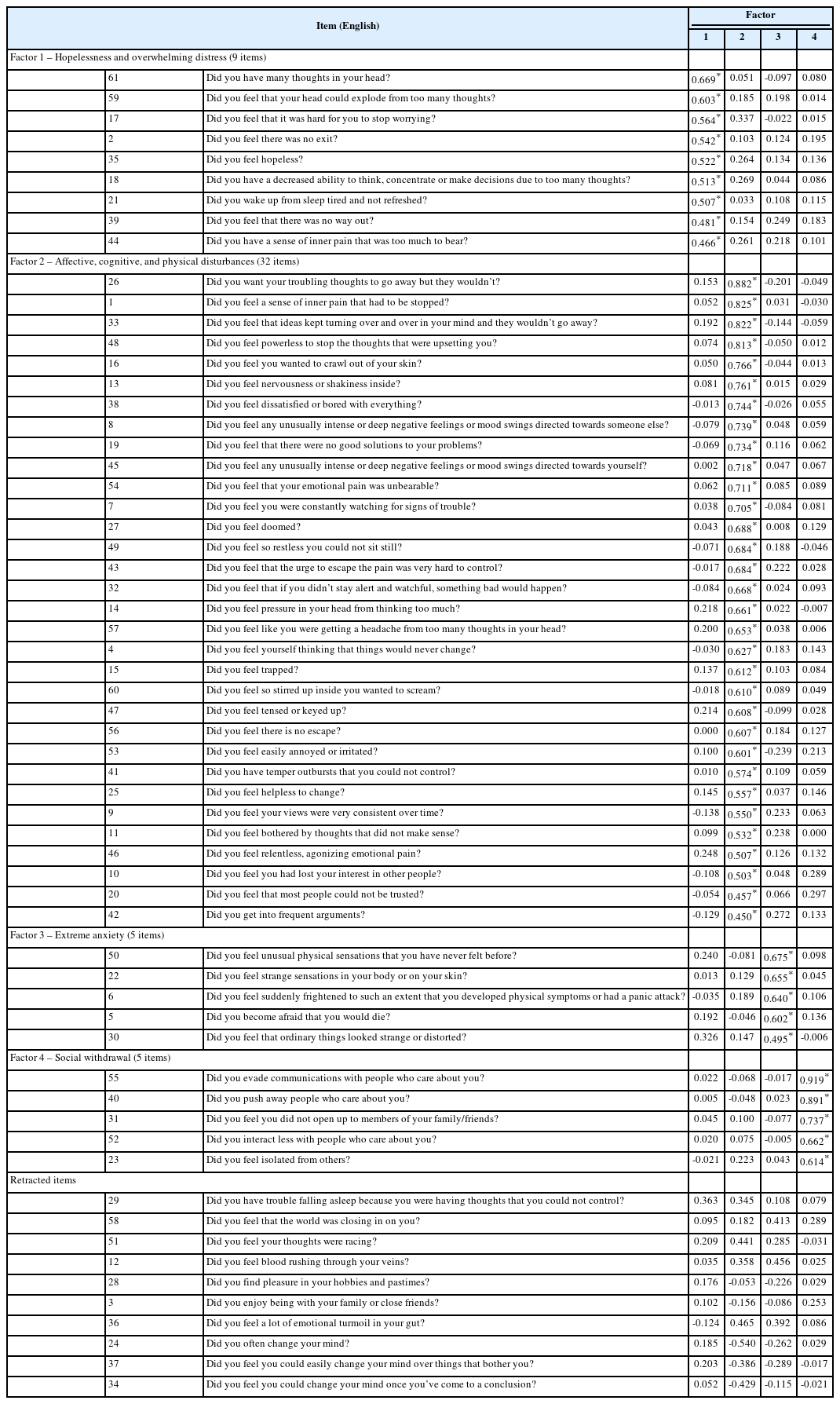

The KMO statistic (0.98) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2[1830]=29944.64, p<0.001) each indicated that there were significant correlations in the data for factor analysis. Results of an EFA suggested a five-factor model of the SCI-2. However, although there were interpretable loadings in the first four factors, the fifth factor consisted exclusively of reversecoded items. This often occurs among reverse-coded items due to possible shared covariances [60] and is often considered to reflect poor model fit [61]. Accordingly, the four-factor model was retained for subsequent analyses. The full factor structure, including each factor’s corresponding items (in English), is presented in Table 3. Three items (items 12, 29, and 36) significantly loaded on multiple factors, whereas two items (items 3 and 28) did not load on any factor; thus, these items were removed from the scale and subsequent analyses. Additionally, three reverse-coded items (items 24, 34, and 37) negatively loaded onto a factor, inconsistent with their theoretical conceptualization; these items were also removed from the resultant scale. All factors were significantly correlated with each other, r=0.62–0.85, ps<0.01, consistent with the conceptualization of the SCS as a strongly related construct.

The first factor, called hopelessness and overwhelming distress, included 9 items assessing features of cognitive disturbances including uncontrollable thoughts, hopelessness, and inescapable feelings as well as insomnia and emotional pain. The second factor, named affective, cognitive, and physical disturbances, included 32 items that loaded various items related to a range of symptoms including entrapment, emotional pain, agitation, anhedonia, irritability, rumination, and failed thoughts suppression. The third factor incorporated 5 items measuring aspects of anxiety and bodily symptoms and was thus called extreme anxiety. Lastly, the fourth factor contained the same 5 items from the original questionnaire and was labeled social withdrawal as it evaluated one’s desires of and responses to social interactions.

CFA

Results of the four-factor CFA, with factors derived from the results of the EFA exhibited good model fit (χ2[1319]=3132.56, p<0.001, CFI=1.00, TLI=1.00, RMSEA=0.05, SRMR=0.04). Standardized factor loadings for each model are presented in Table 3. All latent factors in the four-factor model were significantly related to each other (r=0.70–0.92, ps< 0.001).

Reliability and validity of the SCI-2

Internal consistency

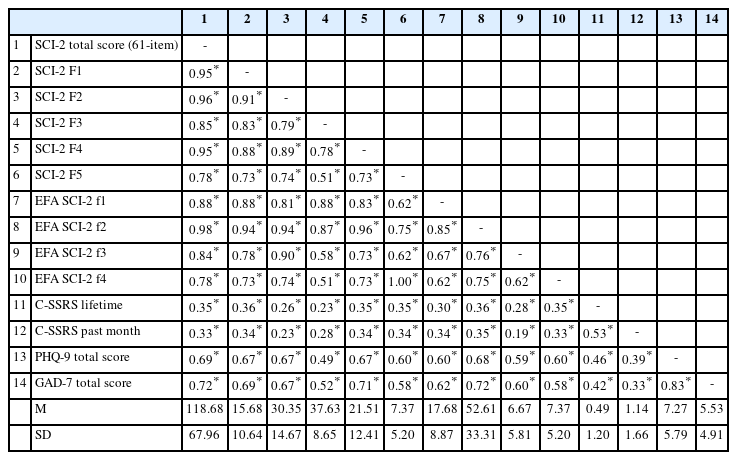

Internal consistencies of the one-factor, five-factor, and four-factor models were evaluated with Cronbach’s alpha and are presented in Table 4. The full 61-item scale for the one-factor model had excellent reliability with an alpha value of 0.98. For the five-factor model, each of the factors presented high reliability with α=0.95 for entrapment, α=0.93 for affective disturbance, α=0.86 for loss of cognitive control, α=0.93 for hyperarousal, and α=0.90 for social withdrawal.

The full 53-item Korean version of the scale also presented excellent reliability with an alpha value of 0.98. Each of the factors also had high reliability with α=0.93 for hopelessness and overwhelming distress, α=0.98 for affective, cognitive, and physical disturbances, α=0.89 for extreme anxiety and α=0.90 for social withdrawal.

Concurrent validity

To assess the concurrent validity of the questionnaire to examine whether the full 61-item Korean version of the SCI-2 similarly measures the construct of suicidality, we evaluated correlations between the current scale with lifetime and past month suicidality employing the C-SSRS. There was a significant, yet moderate, correlation with coefficients r=0.35, p< 0.01 and r=0.33, p<0.01, respectively. PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales were also significantly correlated with the SCI-2 total score with correlations of r=0.69, p<0.01 and r=0.72, p<0.01, accordingly. Negligible correlations were discerned between extreme anxiety with lifetime (r=0.28, p<0.01) and past month (r=0.18, p<0.01) SI. Detailed results are presented in Table 5.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to examine the factor structure and the validity of the SCI-2 in a sample of South Korean participants. As posited in our first hypothesis, CFA results of the one-factor and five-factor models exhibited strong model fits which indicate that SCI-2 can be used in its current 61-item version in Korea as in the United States. To examine alternative factor structures, we conducted an EFA in which results yielded a four-factor model with 53 items and showed similarities with the results of the SCS network analysis [42] where the second factor incorporated components of helplessness and loss of cognitive control. Finally, internal consistency, reliability, and validity of the inventory were examined as appropriate.

According to our EFA results, the first factor mainly embodied aspects of hopelessness (e.g., Did you feel hopeless?) and overwhelming thoughts that are difficult to control (e.g., Did you feel that your head could explode from too many thoughts?) with one emotional pain item (Did you have a sense of inner pain that was too much to bear?) and one insomnia item (Did you wake up from sleep tired and not refreshed?). Together, we titled it hopelessness and overwhelming distress. Hopelessness is a psychological construct that has been identified as one of the major red flags for suicide risk [62-65]. In a 10-year longitudinal study, Beck et al. [63] found that intense hopelessness significantly accounted for future suicide. In addition, in various theories of suicide, such as the Three-Step Theory (3ST) [66] and the interpersonal theory of suicide [39,40,67], hopelessness is regarded as one of the key contributors to suicidal thoughts and behaviors. In addition, having uncontrollable, overwhelming thoughts (also known as ruminative flooding) is another major risk factor for suicide [18]. As regards to the original SCI-2, this first factor was comprised of hopelessness items from the entrapment factor and ruminative flooding items from loss of cognitive control factor. On the other hand, items related to helplessness (e.g., Did you feel helpless to change?) from the entrapment factor loaded under factor 2 along with emotional, cognitive, and physical disturbances. A core difference of frantic hopelessness/entrapment from hopelessness and overwhelming distress is that the former does not incorporate symptoms of ruminative thoughts and emphasizes an intense sense of doom [12,68]. Consistently, a network analysis of the SCS indicated that entrapment and ruminative flooding are strongly connected to other SCS symptoms [42], suggesting that they are central or facilitating factors among other crisis symptoms. As such, a combined state of hopelessness and overwhelming distress may be a subsyndrome of suicide crisis in a Korean sample. Similar to the network analysis of the SCS [42], uncontrollable hopelessness manifested in factor 1 may be a core suicide crisis symptom cluster across the culture.

The second factor had the most item loadings encompassing diverse symptoms of the helplessness part of entrapment, emotional pain, rapid spikes of negative emotions, acute anhedonia, irritability, agitation, hypervigilance, and rumination. It was challenging to develop a name of its own as it incorporated a mixture of affective and cognitive disturbances, coupled with hyperarousal manifestations. A possible explanation for this is that certain symptoms co-occur and interact with others during states of suicidal crisis. By integrating these features, we decided to label the factor as affective, cognitive, and physical disturbances. In fact, the second factor included most of the items from the affective disturbance, loss of cognitive control, and hyperarousal factors of the original SCI-2. We believe that cultural differences play role in the assemble of these affective characteristics. As De Vaus et al. [69] indicated, Eastern culture and Western culture differ in how people interpret and react to negative emotions. Unlike Westerners, Easterners embrace a holistic style and process information integrating the whole context. In Korea particularly, a cultural syndrome of “hwa-byung” exists, in which people experience a mixture of emotional, cognitive, and physical symptoms [70-72]. As such, the factor structure of the English version of the SCI-2 loads items by the different emotional states while the Korean version coalesces many of the affective disturbance characteristics together. In addition, with regards to cognitive disturbances, we noticed a subtle difference among the items that were divided into factor 1 and factor 2. Among the items relevant to ruminative flooding, those in factor 1 asks about the repercussions of ruminating (e.g., Did you have a decreased ability to think, concentrate or make decisions due to too many thoughts?), whereas items in factor 2 inquires one’s physical conditions (e.g., Did you feel pressure in your head from thinking too much?).

The third factor, extreme anxiety, incorporated symptoms of anxiety accompanying panic-like symptoms and unusual or strange sensations. These items were originally a subscale that belonged to the affective disturbance factor in the SCI-2 English version; however, they loaded as a separate factor in our analysis. The content in the factor is related to frantic worry accompanied by physical symptoms or sensory distortion (e.g., Did you feel that ordinary things looked strange or distorted?). It is notable that only extreme anxiety subscale resulted in a distinct symptom cluster from the other three subscales of affective disturbance of the SCS diagnostic criteria, which were mostly loaded on factor 2. One potential explanation for this outcome is that our data was based on a community sample whereas the SCI-2 English version was validated in clinical samples. Further, this factor was originally developed based on research that panic-like symptoms and sensory distortions predict suicide attempt among psychiatric patients [43,73]. Further examination of the utility of this factor is warranted.

The final factor, titled social withdrawal, is the only factor that loaded identical items as the original questionnaire evaluating respondent’s relationship with others (e.g., Did you feel isolated from others?). As claimed in the interpersonal theory of suicide, lacking sense of belongingness is a detrimental risk factor for suicidal behavior [39]. The two constructs in the theory, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensome, both elaborate on the social triggers that engender suicidal desires [67]. Examples include not receiving appropriate reciprocal care from families and friends as well as the incorrect interpretation of the need to sacrifice to prevent being a burden to others. Overall, the factor analysis suggests that four distinct factors are inherent in the Korean version of the SCI-2.

Reliability and concurrent validity of the inventory were examined through correlations and Cronbach’s alpha values, respectively. Interestingly, the correlation between the SCI-2 and the C-SSRS, both assessing levels of suicidality, was relatively moderate. One possible explanation for this observation is that the questions from the C-SSRS that were selected for this study assess SI while the SCI-2 is theorized to measure one’s risk for imminent suicidal behavior. A bulk of former studies have claimed that not everyone who harbors SI necessarily attempts suicide [74-76] and the recent validation study of the SCI-2 suggested that this measure is a better predictor of suicidal behaviors [41]. Additionally, the timeframe that the two assessments base their questions on are also different: the SCI-2 inquires about one’s state for the past several days, whereas the C-SSRS asks about one’s ideation over the past month and across one’s lifetime. The results of the current study are promising in that novel tools are being developed to assess near-term suicide risk. Such instruments could be more clinically informative and effective in ameliorating rates of deaths by suicide.

Our CFA results indicate that the model fit of the one-factor, original five-factor, and four factor structures are all relevant with excellent fit scores. Conceptually, the original subfactors of emotional, cognitive, physical, and social disturbances of the SCI-2 are well defined [41]. Empirically, however, clinical manifestations of those disturbances could differ across nations, society, or cultural contexts. Considering that suicide is an outcome of complex and heterogeneous factors, the single factor solution may provide a stable construct across countries, while different factor models may help enhance our understanding of culture-specific clinical manifestations of the suicide crisis. As this study is the first validation study of the SCI-2 in an Eastern population, further examination and replication studies are needed to generalize these findings.

Limitations are inherent in the current study. First, our sample was not representative of a diverse group since demographic characteristics ratios were not proportionate. For example, data from older participants (e.g., over 40) was limited. Since data collection was entirely conducted online, it may have been cumbersome for participants who are not familiar with social media to complete it. In this context, these results may not be generalizable to those who are unfamiliar with social media and technology. Also, our results are based on data from a community sample and therefore are not generalizable to clinical samples. Second, considering that our data was collected during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic when people experienced drastic changes in their daily lives, it is probable that levels of depression, anxiety, and suicidality were reported relatively higher than they would have been without the pandemic extant throughout the study [77]. Third, due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, the current study was unable to examine the predictive validity of the SCI-2. Thus, further study with a longitudinal study design would advance current findings. Finally, the study was short in providing sensitivity, specificity, and cutoff point by the SCS diagnosis as it was a cross-sectional study. Future studies should attempt to examine these aspects for it will elevate improved near-term suicide risk assessment.

Moving onward, we suggest that future studies attempt to validate the Korean version of the SCI-2 in a range of community and clinical samples in order to examine the generalizability of the inventory. In addition, it would be beneficial if researchers could identify possible subconstructs that is inherent in factor 2, affective, cognitive, and physical disturbances, as it consists of the most items. Upon inspecting the items that are loaded under this factor, it may be viable, for instance, to divide affective disturbances (e.g., Did you feel relentless, agonizing emotional pain?) from cognitive disturbances (e.g., Did you want your troubling thoughts to go away but they wouldn’t?) and physical disturbances (e.g., Did you feel tensed or keyed up?). As such, further investigating and refining the inventory will be valuable in supporting the clinical utility of the SCI-2.

In conclusion, the proposed one-factor and five-factor models of the SCI-2 present strong model fits. Our four-factor model also helps delineate potential critical symptoms that must be flagged when assessing risk for suicide in Korea. This alternative factor structure constitutes a total of 53 items that are organized under hopelessness and overwhelming distress (factor 1), affective, cognitive, and physical disturbances (factor 2), extreme anxiety (factor 3), and social withdrawal (factor 4). The factor structure of the inventory may be culture-sensitive and thus requires further study. Although the results are exploratory in nature, our efforts in redefining traditional suicide risk assessments (e.g., detecting presence of SI or history of suicide attempts) seem promising. It is critical to identify symptoms, or possibly profiles, that are immanent among suicidal individuals in a more objective manner as not everyone is transparent about their suicidal desires. Especially, given the low rates of mental health service utilization in Korea, it would be ideal to develop a scale that is applicable for both patients and non-patients. Developing tools to discern individuals with imminent suicide risk will significantly contribute to the suicide literature. Furthermore, it will be clinically beneficial such that psychologists will be able to acknowledge individuals who are at high-risk and thus implement necessary preventive measures in advance to impede one from attempting suicide.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ji Yoon Park, Sungeun You. Data curation: Ji Yoon Park, Jenelle A. Richards, Sungwoo Lee. Formal analysis: Ji Yoon Park, Megan L. Rogers. Investigation: Sarah Bloch-Elkouby, Igor Galynker. Methodology: Ji Yoon Park, Megan L. Rogers, Sungeun You. Supervision: Igor Galynker, Sungeun You. Funding acquisition: Sungeun You. Writing—original draft: Ji Yoon Park, Megan L. Rogers. Writing—review & editing: all authors.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF2020S1A5A2A03044181).