Improvement of Screening Accuracy of Mini-Mental State Examination for Mild Cognitive Impairment and Non-Alzheimer's Disease Dementia by Supplementation of Verbal Fluency Performance

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate whether the supplementation of Verbal Fluency: Animal category test (VF) performance can improve the screening ability of Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for mild cognitive impairment (MCI), dementia and their major subtypes.

Methods

Six hundred fifty-five cognitively normal (CN), 366 MCI [282 amnestic MCI (aMCI); 84 non-amnestic MCI (naMCI)] and 494 dementia [346 Alzheimer's disease (AD); and 148 non-Alzheimer's disease dementia (NAD)] individuals living in the community were included (all aged 50 years and older) in the study.

Results

The VF-supplemented MMSE (MMSE+VF) score had a significantly better screening ability for MCI, dementia and overall cognitive impairment (MCI plus dementia) than the MMSE raw score alone. MMSE+VF showed a significantly better ability than MMSE for both MCI subtypes, i.e., aMCI and naMCI. In the case of dementia subtypes, MMSE+VF was better than the MMSE alone for NAD screening, but not for AD screening.

Conclusion

The results support the usefulness of VF-supplementation to improve the screening performance of MMSE for MCI and NAD.

INTRODUCTION

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)1 is a widely used brief screening tool for the detection of cognitive impairment. In spite of its briefness and practical usefulness, it has a couple of important limitations for the early detection of cognitively impaired states. First, MMSE has poor sensitivity in detecting mild cognitive impairment (MCI),2,3 an at-risk state for the development of dementia,4,5 although early detection of the pre-dementia state is increasingly important, with high possibilities for the development of disease modifying treatments for Alzheimer's disease (AD) and related dementias. Second, MMSE consists of test items primarily covering orientation, attention, memory and language, and is less sensitive to frontal executive dysfunction.2,6 While memory decline is the earliest and most important cognitive deficit in amnestic MCI (aMCI) and AD, frontal executive dysfunction is frequently more prominent than memory or other cognitive deficits in non-amnestic MCI (naMCI) and non-Alzheimer's disease dementia (NAD), especially frontotemporal dementia (FTD)7 and vascular dementia (VD).8 Therefore, the assessment of frontal executive dysfunction could make a meaningful contribution to the screening of overall MCI and dementia, or naMCI and NAD.

Verbal Fluency: Animal category test (VF) provides an assessment of semantic fluency by asking subjects to name as many animals as possible within 1 minute.9 Semantic fluency has been shown to be reduced in subjects with MCI compared to those who are cognitively normal (CN).10 Furthermore, semantic fluency involves not only the ability to search semantic memory using categorical rules, but also to look for the executive function required to track prior responses and block intrusions from other semantic categories.11 These imply that VF-supplementation has been proposed to improve the MCI and dementia screening ability of MMSE. Nevertheless, the effect of supplementing VF to MMSE score on the accuracy of MCI and dementia screening was poorly investigated.

In this study, we aimed to investigate whether the supplementation of VF performance can improve the screening ability of MMSE for MCI, dementia and their major subtypes.

METHODS

Subjects

Study subjects were recruited from a pool of individuals registered in a program for the early detection and management of dementia at four centers located in Seoul, Korea (two public health centers, one senior citizens welfare center and one dementia clinic) from January 2000 to May 2011. In this study, 655 CN, 366 MCI (282 aMCI; 84 naMCI) and 494 dementia (346 AD; 148 NAD) individuals living in the community were included (all aged 50 years and older).

A diagnosis of dementia was made according to the criteria of the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.12 AD was diagnosed according to the probable or possible AD criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA).13 VD was diagnosed according to the probable or possible VD criteria of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l'Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS-AIREN).14 Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) or Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD) was diagnosed according to the DLB consensus criteria,15 and FTD was diagnosed according to the FTD consensus criteria.16 MCI was diagnosed according to the current consensus criteria.17 All MCI individuals had an overall clinical dementia rating scale (CDR)18 of 0.5. All NC subjects received a CDR score of 0. The exclusion criteria for all subjects included any present serious medical, psychiatric and neurologic disorders which could affect the mental function; the presence of severe behavioral or communication problems which would make a clinical examination difficult; an absence of a reliable informant; and the inability of reading Korean [i.e., inability of reading 10 words in the Word List Memory from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's disease (CERAD) neuropsychological battery19,20]. All Individuals with minor physical abnormalities (e.g., diabetes with no serious complications, essential hypertension, mild hearing loss or others) were included. The Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital, Korea approved the study, and subjects or their legal representatives gave written informed consent.

Clinical and neuropsychological assessments

All subjects were examined by psychiatrists with advanced training in dementia research according to the CERAD protocol.19,20 The CERAD clinical assessment battery included CDR,18 Blessed Dementia Scale-Activities of Daily Living (BDS-ADL), general medical examination, neurologic examination, laboratory tests, and brain MRI or computed tomography. The standard administration of the CERAD battery was previously described in detail.19,20 Reliable informants were necessarily interviewed to acquire the accurate information regarding the cognitive, emotional and functional changes as well as the medical history of the subjects.

MMSE, VF and other neuropsychological tests (15-item Boston Naming Test, Word List Memory, Word List Recall, Word List Recognition, Constructional Praxis, and Constructional Recall) included in the CERAD neuropsychological battery were applied by experienced clinical psychologists or nurses. The VF-supplemented MMSE (MMSE+VF) score was derived from simply summing the scores of the two tests.

A panel consisting of four psychiatrists with expertise in dementia research made the clinical decisions, including diagnosis and CDR, after reviewing all the available raw data.

Statistical analysis

Between-group comparisons for continuous data, including demographic and clinical data, were performed by two-tailed t tests. Categorical data were analyzed by the χ2 test. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to compare the screening accuracy for MCI, dementia and their subtypes between MMSE and MMSE+VF. The area under the curve (AUC) of the ROC curve was compared by using the method of Hanley and McNeil.21

The level of statistical significance was set as two-tailed p<0.05. ROC curve analyses were performed by using MedCalc for Windows, version 12.1 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). All other analyses, except the ROC curve analysis, were performed by using SPSS software, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects are summarized in Table 1.

ROC analysis

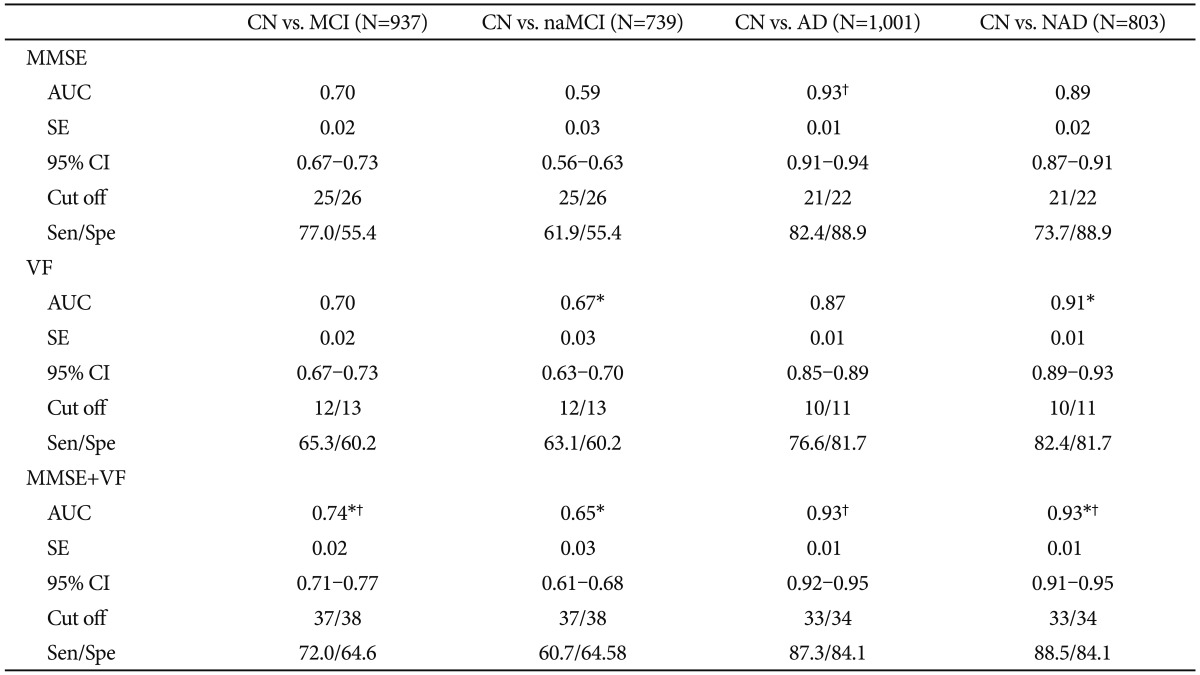

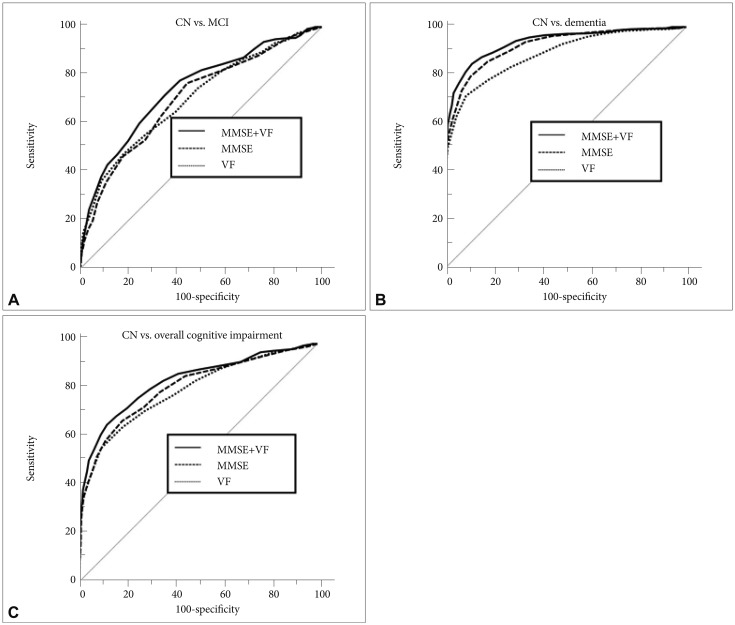

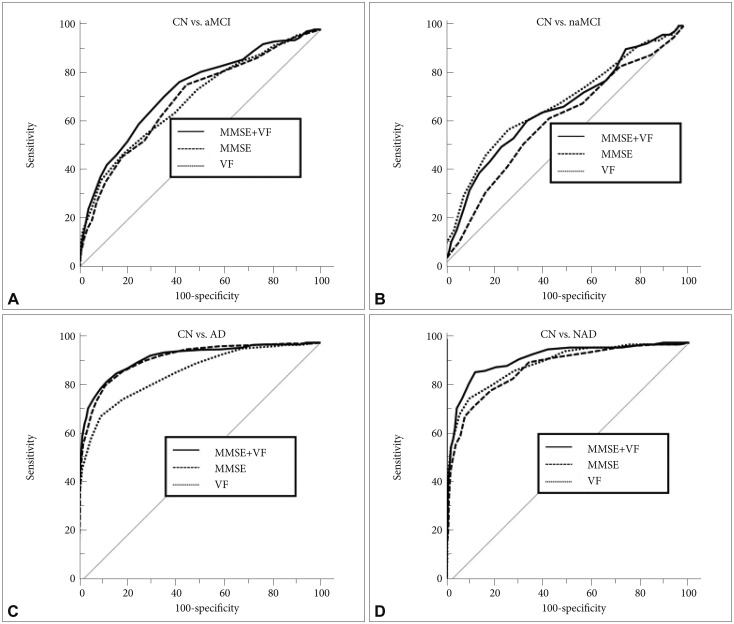

The ROC curve was constructed for each score, as shown in Figures 1 and 2, and the AUC for each ROC curve was calculated. AUC, sensitivity, specificity, cutoff points of MMSE, VF and MMSE+VF scores are shown in Table 2 and 3. The results of the ROC curve comparisons between the MMSE raw score and MMSE+VF score are as follows:

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Verbal fluency (VF) and VF-supplemented MMSE (MMSE+VF) in cognitive impairment screening for (A) cognitively normal (CN) versus mild cognitive impairment (MCI), (B) CN versus dementia and (C) CN versus overall cognitive impairment (MCI plus dementia).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Verbal Fluency (VF) and VF-supplemented MMSE (MMSE+VF) in cognitive impairment screening for (A) cognitively normal (CN) versus amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI), (B) CN versus non-amnestic MCI (naMCI), (C) CN versus Alzheimer's disease (AD) and (D) CN versus non-Alzheimer's disease dementia (NAD).

Area under the curves (AUC) and cutoff scores of MMSE, VF, and MMSE+VF in CN, dementia and overall cognitive impairment (MCI+dementia) groups

Screening of MCI, dementia and overall cognitive impairment

MCI screening accuracy of MMSE+VF was significantly better than that of MMSE (z=3.486, p=0.0005) (Table 2, Figure 1A). MMSE+VF showed a significantly superior dementia screening accuracy to MMSE (z=2.881, p=0.0040) (Table 2, Figure 1B). MMSE+VF also showed a significantly superior overall cognitive impairment screening accuracy to MMSE (z=4.046, p=0.0001) (Table 2, Figure 1C).

Screening the subtypes of MCI and dementia

MMSE+VF showed a significantly better screening accuracy for both aMCI and naMCI compared to the MMSE alone (z=2.992, p=0.0028 for aMCI; z=2.387, p=0.0170 for naMCI) (Table 3, Figure 2A and B). Among the 84 subjects with naMCI, 9 subjects with a single domain naMCI scored worse on only the VF test. In order to minimize the concern, we performed additional analyses on all subjects, excluding the 9 subjects (n=1,506). In this operational condition, we found that MMSE+VF had a significantly better screening ability for MCI (z=3.024, p=0.0025) and overall cognitive impairment (z=3.685, p=0.0002) than MMSE. Regarding the dementia subtypes, MMSE+VF was significantly better than MMSE for NAD screening (z=4.186, p<0.0001) (Table 3, Figure 2D), but not for AD screening (z=0.810, p=0.4182) (Table 3, Figure 2C).

DISCUSSION

We found that MMSE+VF had a significantly better screening ability for MCI, dementia and overall cognitive impairment compared to the MMSE alone. For additional subtype analyses for MCI and dementia, we also found that it showed a significantly better ability than MMSE for both MCI subtypes and NAD screening, but not for AD screening.

MMSE also has poor sensitivity in detecting MCI, and is less sensitive to frontal executive dysfunction. Standish, Molloy, Cunje and Lewis22 found that a subtest of fluency (type not specified) was best able to discriminate between CN and MCI subjects after controlling for age and education. Saxton et al.23 suggested that semantic fluency (fruit category) showed a significant baseline decline in 1.5-5 years prior to the onset of AD. Furthermore, sematic fluency involves various executive functions which support or enable the semantic retrieval processes, such as systematic searching and avoiding perseverations and non-category intrusions.24,25 These imply that the supplementation of VF has been proposed to improve the MCI and dementia screening accuracy of MMSE.

In the MCI screening, we performed an ROC curve analysis that showed the AUC of 0.718 for MMSE+VF in spite of the VF-supplementation, which improves the screening ability of MMSE. This finding may be explained by two possibilities. First, this modest level of AUC is influenced by poor sensitivity in detecting MCI by MMSE itself rather than by the VF-supplementation effect. Second, the MCI group is comprised of subjects with very heterogeneous cognitive impairments rather than homogeneously prominent executive deficits.

There is several evidence that executive deficits are an important feature of the cognitive decline as well as episodic memory deficits in AD, and that these deficits typically occur early in the disease, and may be the first non-memory deficits to occur.26,27 However, in our study, we discovered the VF-supplementation effect only for NAD screening, not for AD screening. This is probably associated with the fact that the frontal executive function is relatively more impaired in NAD, particularly FTD28,29 and VD8 compared to AD. Furthermore, the lowered VF-supplementation effect on AD screening in this study is likely to be a reflection of the heterogeneous nature of AD that may include subjects with subtle executive deficits, which may be undetected by VF-supplementation performance.

Several scales have been proposed to overcome the shortcomings of MMSE in MCI and NAD screening by inserting or modified VF, such as the Concise Cognitive Test (CONCOG),30 the 7-Minutes Screen (7MS)31 and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).32 Srinivasan30 suggested that CONCOG has negligible ceiling effects compared with the MMSE. Meulen et al.33 demonstrated that the sensitivity of the 7MS for NAD was 89.4% with a specificity of 93.5%. Dong et al.34 indicated that MoCA is superior to the MMSE in the screening of patients with MCI who are at a higher risk for incident dementia. Lee et al.35 suggested that MoCA had an excellent sensitivity of 89% and good specificity of 84% for MCI screening. Though these scales have demonstrated better screening accuracy for MCI or NAD compared with the MMSE, these scales are not widely used in Korean clinical settings due to their unfamiliar westernized items. Therefore, VF-supplementation was selected to improve the screening ability of MMSE for MCI and NAD in our study.

The strengths of this study lead us to believe that our findings will be replicated in other settings and populations. First, our study population was rather large and had strict diagnoses of CN, MCI, dementia and their subtypes. These were conducted through a clinical evaluation using the strict diagnostic criteria by a panel consisting of four psychiatrists [two panel members (DYL and KWK) were certified as CDR raters by the Memory and Aging Project of the AD Research Center at the Washington University School of Medicine] with expertise in this area. This may have increased the reliability and generalizability of our data. Furthermore, MMSE+VF has an important cost-effect perspective related with the superior MCI and NAD screening accuracy but with a little burden on clinicians. Moreover, it could be broadly applied in some specialized clinical settings (e.g., stroke clinic) with benefits due to its superior NAD screening accuracy.

In conclusion, our findings strongly support the usefulness of VF-supplementation to improve the screening performance of MMSE for MCI and NAD.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Healthcare technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (Grant No. A092145) and a grant from KIST Open Research Program (Grant No. 2013-1520).