Effects of Envy on Depression: The Mediating Roles of Psychological Resilience and Social Support

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Envy, as a stable personality trait, can affect individuals’ mental health. Specifically, previous studies have found that envy can lead to depression; however, the mechanism by which envy affects depression is still unclear. Therefore, based on the resilience framework, we used structural equation modeling to explore the mediating roles that social support and psychological resilience play between envy and depression.

Methods

Chinese college students (n=680) were recruited to complete four scales: the Dispositional Envy Scale (DES), the Symptom Checklist 90-Depression Subscale (SCL-90-DS), the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), and the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS).

Results

The results confirmed that both social support and psychological resilience are significant mediators between envy and depression. Furthermore, social support plays a significant mediating role between envy and psychological resilience, and psychological resilience plays a significant mediating role between social support and depression. Specifically, the results indicated that envy not only directly increases the likelihood of developing depression, but also indirectly increases the likelihood of developing depression by affecting psychological resilience through negatively influencing social support.

Conclusion

This study provides a theoretical basis for enhancing psychological resilience and social support in order to ameliorate adverse effects of envy on depression.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years there has been an upsurge in research into depression. Studies have shown that the occurrence and development of depression is affected by many factors, such as genetic factors [1], social and family factors [2], and even personality traits [3]. Envy is one such stable personality trait [4-8]. Individuals with high envy will be more likely to experience inferiority and feelings of ill will [4,8,9-11], thereby affecting their mental health. Meanwhile, previous studies have shown a significant positive correlation between envy and depression [12-15]. However, the mechanism by which envy affects depression is still unclear. Therefore, it is very meaningful to explore this mechanism in order to expand the understanding of the mechanism of depression formation from the perspective of envy.

Interestingly, envy has been shown to be negatively correlated with social support [16]. Social support is an external supporting resource that can also inhibit depression [17-19]. In addition, contrary to envy, which is associated with negative characteristics [8,20], psychological resilience is a protective mechanism associated with positive characteristics [21]. Moreover, previous studies have pointed out that psychological resilience can inhibit the occurrence of depression [22,23]. Therefore, the present study aims to explore the mediating roles of social support and psychological resilience between envy and depression based on the resilience framework theory. The research not only extends the resilience framework theory, but also provides a new practical perspective for the prevention and treatment of the impact of envy on depression.

The relationship between envy and depression

Depression is an individual’s negative view of the self, the world, and the future, as well as uncontrollable and frequent negative thoughts [24], characterized by pessimism, self-denial, compliance, and self-accusation [25,26]. Research shows that personality traits are one of the influencing factors of depression [3]. Envy is one such personality trait [4-8]; people with high envy levels are more sensitive to information in social comparisons, thus leading to feelings of individual inferiority, resentment, hostility, and so on [4,8,11]. Social comparison theory states that people generally choose to compare themselves with others who are close to their own abilities and opinions [27]; however people generally perceive themselves to be better than they objectively are [28]. Therefore people tend to make upward social comparisons, that is, compare themselves to those who are actually more able, have more possessions, and so forth [29]. Individuals with high levels of envy will find these differences more salient and face more negative experiences as a result [8,11]. These include feelings of inferiority and dejection, which may lead to depression [12]. Moreover, some empirical studies have indicated a positive correlation between envy and depression [13-15]. Based on the literature, this study also hypothesizes that envy can positively predict depression.

The mediating effect of psychological resilience and social support

Psychological resilience can be defined as a tendency to overcome and actively adjust to adversities and stress [30]. It includes tenacity, self-efficacy, tolerance of negative affect, and other internal protection factors [21,31]. According to the resilience framework, when people face stressors and challenges, the interaction between their external environment and psychological resilience will affect how well they adapt to adversity [32]. If people do not adapt well, they may experience depression [33]. Therefore, psychological resilience may be the explanatory mechanism of envy and depression. Moreover, some studies have shown that negative personality traits can negatively affect self-efficacy [34,35], one of the characteristics of psychological resilience [31]. Envy is a negative personality trait [4], thus envy may reduce self-efficacy. As such, we hypothesized that envy may negatively affect psychological resilience. In addition, numerous studies have reported a negative correlation between psychological resilience and depression [17,36,37]. Therefore, people with high levels of envy may have lower levels of psychological resilience, which may in turn increase depression. Based on the above evidence, we further hypothesized that psychological resilience plays a mediating role in envy and depression.

Social support refers to the spiritual and material support, including love, care, and respect, that individuals obtain from social relations such as family, colleagues, groups, organizations, and communities [38]. This support can alleviate people’s psychological stress response, relieve their nervous state, and improve their social adaptability [39]. In addition, based on the resilience framework [32], when people face stressors and challenges, external support resources from family, society, and peers interact with internal psychological resilience factors. When people face negative experiences, they perceive less external social support resources which lowers the level of psychological resilience, lead to maladjustment [32], and may ultimately lead to depression [33]. Moreover, previous research has discussed the relationship between envy and social support. Such as Xiang et al. [16], who reported a negative correlation between envy and social support. The mechanism may be that envy can lead to cheating [40] and aggressive behaviors [41], which may damage that individual’s interpersonal relationships and make them less likely to perceive and accept social support [42]. In addition, many studies have shown that there is a negative correlation between social support and depression [43-48]. Thus people with high levels of envy may perceive less social support, which may increase depression. Therefore, social support may also be an explanatory mechanism for envy and depression. Based on the above analyses, we hypothesized that social support plays a mediating role in the influence of envy on depression.

Furthermore, according to the resilience framework, when people face stressors and challenges [32], the lower the external support resources, the lower the individual’s psychological resilience will be which will lead to the individual’s negative adaptation to adversity [49,50]. Furthermore, people with high levels of envy may perceive less social support compared to their peers, leading to lower levels of psychological resilience, which may increase depression. For these reasons, we further hypothesized that envy may also negatively affect psychological resilience through its negative influence social support, thereby indirectly increasing depression.

The present study

The present study aims, based on the resilience framework, to explore the mediating mechanisms of social support and psychological resilience in the relationship between envy and depression. Based on the literature described above, we proposed four hypotheses: 1) there is a significant positive correlation between envy and depression. 2) There is a significant negative correlation between envy and psychological resilience. 3) Social support and psychological resilience both play significant roles in mediating envy and depression. 4) Envy may also negatively affect psychological resilience through its negative influence social support, thereby indirectly increasing depression.

METHODS

Participants and procedures

In the study, 680 participants were recruited by random sampling method and cluster sampling method, including 186 men and 494 women. The average age were 19.16±2.39 years, and the age range was 17 to 26 years. All the participants were recruited from South China Normal University, Jinan University, South China University of Technology, and Hunan Normal University. None of the participants had any physical or mental health problems. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Academic Committee of the School of Psychology of Hunan Normal University. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Academic Committee of the School of Psychology of Hunan Normal University (Approval number: 076). In addition, it should be noted that as our questionnaire collection work is carried out in several batches, about 20 researchers have participated in this questionnaire collection work successively.

A series of questionnaires were completed in the form of group test, including four questionnaires needed in this study, the Dispositional Envy Scale (DES), the Symptom Checklist 90-Depression Subscale (SCL-90-DS), the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) and the perceived social support scale (PSSS), as well as brief demographics. The questionnaires used were all in Chinese. The whole process took approximately 40 minutes. Participants all signed the written informed consent forms before participating in the study and were paid upon completion of the whole questionnaires. In addition, we have two exclusion criteria. First, if all questions had the same answer, we think the participant did not answer them seriously, so we can exclude this questionnaires. Second, if more than 2/3 of the questions were not filled out, we considered excluding it. None of the respondents met the second criteria. In addition, numerous studies have shown the effectiveness of this procedures [51-54].

Measures

Dispositional Envy Scale (DES)

The Dispositional Envy Scale (DES) was proposed by Smith et al. [8] to evaluate envy. In this study, we used the Chinese version, which has good reliability and validity (Cronbach’s α= 0.79) [55]. The scale consists of 8 items (e.g., “I feel envy every day.” and “The bitter truth is that I generally feel inferior to others.”), and each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree). Higher scores mean a stronger tendency to experience envy. In this study, the scale was internally consistent and its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.77.

Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS)

The Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) contains 12 items which were divided into three subscales: family support, friend support, and other support [56]. Examples of items are: “I can get emotional help and support from my family when I need it” (family support); “My friends can really help me” (friend support); “Some people (leaders, relatives, colleagues) will appear beside me when I encounter problems” (other support). Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating higher levels of social support (1=strongly disagree, 7=strongly agree). We used the adaptation of Kong et al. [57] to evaluate respondents’ level of social support because it has shown high reliability and validity in Chinese samples. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this scale was 0.90.

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)

There are 10 items in the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), each scored on a 6-point Likert-type Scale (1= almost agree, 6=almost disagree); higher scores indicate higher level of psychological resilience. Examples of items are: “I can deal with whatever comes” and “I can achieve goals despite obstacles”. Campbell-sills and Stein [21] compiled the scale and Kong et al. [58] proved the reliability of the scale in Chinese samples (Cronbach’s α=0.85). In this study, this scale exhibited adequate reliability (α=0.90).

Symptom Checklist 90-Depression Subscale (SCL-90-DS)

The Symptom Checklist 90-Depression Subscale (SCL-90-DS) has 90 items and ten dimensions and is used to evaluate the depression tendency of individuals [59]. Items are scored using a 5-point Likert-type scale (0=no, 4=serious); higher scores indicate higher levels of depression. In this study, the adapted version by Tang and Cheng [60] was used, which has been proved to have high reliability and validity in Chinese populations. In this study, the reliability of the depression subscale was 0.89.

Data analysis

First, we used Amos 22.0 to evaluate the measurement model we built and to test whether our indicators were good predictors of latent variables. We separated the three subscales of social support, divided psychological resilience and depression into three parts, and divided envy into two parts as indicators of factors that use an item-to-construct balance approach [61]. Once the measurement model was fitted, we established a structural model and selected chi-square statistic, comparative fitting index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) as indicators to test the goodness of fit of the model [62]. At the same time, akaike information criterion (AIC) was used as an indicator of the most suitable model; smaller values mean better fit [63]. What’s more, we used the expected cross validation index (ECVI) as an indicator to assess the replication potential of the model; smaller values indicate greater potential replication [64]. In addition, we used Bootstrap estimation procedures to test the mediating effects of social support and psychological resilience between envy and depression. Finally, we tested for gender differences.

RESULTS

Measurement model

The latent variables in the measurement model include envy, social support, psychological resilience, and depression. The results showed that the data was very suitable for the measurement model [χ2 (38, 680)=77.994, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.039; SRMR=0.028; CFI=0.990]. The factor loadings of all potential variables were significantly correlated (p<0.001), which means that the observed variables represented the latent variables well. In addition, as shown in Table 1, all variables were significantly correlated. Table 1 also contains the mean and standard deviation, as well as the correlations between envy, social support, psychological resilience, and depression.

Structure model

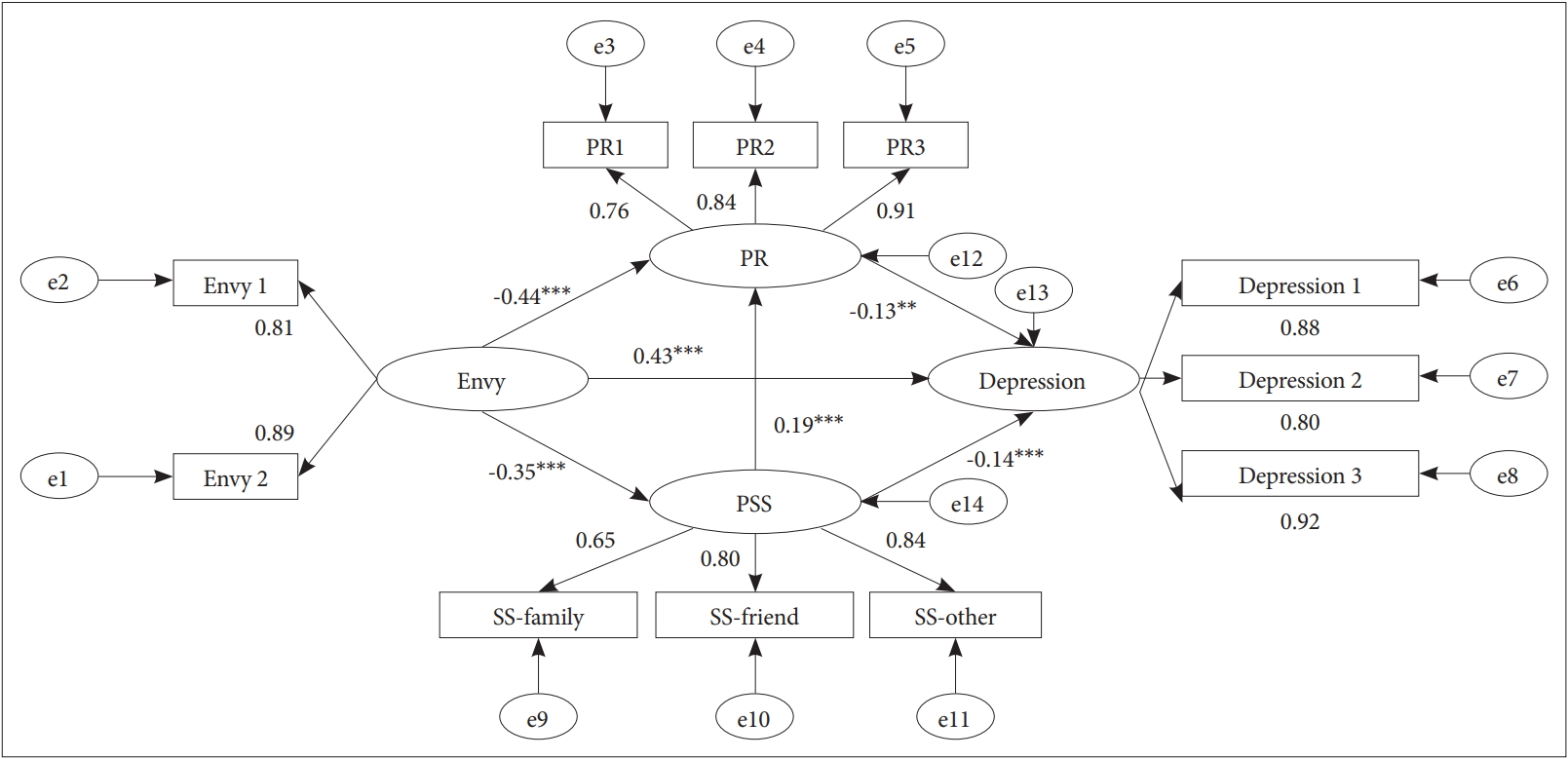

In order to verify our hypothesis, we built Model 1. In this model envy directly predicts depression and also indirectly influences depression through social support and psychological resilience. The results showed that the indicators were well matched (Table 2) [χ2 (38, 680)=77.994, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.039; SRMR=0.028; CFI=0.990]. Based on these, we used Model 1 as the final model (Figure 1).

The mediating model factor loadings were standardized. Envy 1 and Envy 2 are two dimensions of the Envy; PR1 and PR2 are two dimensions of the Psychological Resilience (PR); SS-Family, SS-Friend, SS-Other are three subscales of the Perceived Social Support (PSS); Depression1, Depression 2 and Depression 3 are three dimensions of the depression subscales in the 10 dimensions of the multidimensional Symptom Checklist 90 Scale (SCL-90). **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

The significance test of mediating variables

We used Bootstrap estimation procedures to explore the stability of the mediation variables [65]. We adopted the method of random sampling to extract 2000 Bootstrap samples from the original data (n=680). The results showed that the mediating variables play an important role in the 95% confidence interval. As shown in Table 3, envy has a significant effect on depression, both through social support [95% confidence intervals (0.017–0.095)] and psychological resilience [95% confidence intervals (0.015–0.115)]. In addition, envy has a significant effect on psychological resilience through social support [95% confidence intervals (-0.060–-0.016)] and social support has a significant effect on depression through psychological resilience [95% confidence intervals (-0.040–-0.005)].

Gender differences

We tested the gender differences between the four latent variables: envy, social support, psychological resilience, and depression. Independent samples t-tests showed that there was no significant difference between men and women on envy [t (680)=-0.557, p=0.577] or depression [t (680)=-0.327, p=0.744]. However psychological resilience [t (680)=2.050, p=0.041] and social support had significant gender differences [t (680)=-2.454, p=0.014]; psychological resilience was higher in men than women, while the level of social support was higher in women than men. On this basis, we further studied the stability of our structural model.

We used multi-group analysis to ascertain whether there were significant differences in the path coefficients in the transgender model. Referring to the study of Bertera [66], we established two models and maintained the stability of basic parameters (factor loadings, error variance, and structural covariance). One allows free estimation of cross-gender paths (unconstrained structural paths), while the other limits path coefficients between two genders (constrained structural paths). The results confirmed significant differences between the two models [Δχ2 (17, n=680)=57.742, p=0.001]. At the same time, comparing the other parameters in the two models showed that both models have a good fit (Table 4). Therefore, multi-group deformation models with limited parameters are generally acceptable. In addition, we further calculated the critical ratio of standard deviation (CRD) to explore the gender differences in specific paths. According to the decision rule, the absolute value of CRD is greater than 1.96, which indicates that there is a significant gender difference between the two paths (p<0.05). The results showed significant gender differences in the structural paths from envy to psychological resilience (CRDEnvy→PR=2.112). There were also significant gender differences in the structural paths from social support to psychological resilience (CRDPSS→PR=3.370). However, there were no significant gender differences from envy to psychological resilience (CRDEnvy→PR=0.485), from psychological resilience to depression (CRDEnvy→PSS=1.686), from envy to social support, or from social support to depression (CRDPSS→Depression=-0.489).

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed, based on the resilience framework, to explore the mediating roles of social support and psychological resilience between envy and depression. The results confirmed that envy was positively correlated with depression. At the same time, the results showed that there was a significant negative correlation between envy and psychological resilience. Moreover, social support and psychological resilience played significant mediating roles between envy and depression. In addition, the results also showed that envy indirectly positive affect people depression trend by negatively affecting psychological resilience through negatively influencing social support. Thus, all four hypotheses were confirmed.

The relationship between envy and depression

According to the correlation analysis, there was a significant positive correlation between envy and depression,which verifies hypothesis 1. People with high levels of envy are more concerned about self-deficiency and other people’s possessions and are more likely to experience negative experiences such as inferiority and dejection as a result [4-8,20]. These feelings may subsequently lead to depression [12].

The relationship between envy and psychological resilience

In addition, there was also a negative correlation between envy and psychological resilience, which was confirmed by the regression coefficient in the structural equation model. In other words, higher levels of envy indicated lower levels of psychological resilience, which verifies hypothesis 2. Firstly, envy as a negative personality trait [4-8] may reduce people’s self-efficacy, which was one important positive component of psychological resilience [31]; thus there was a negative correlation between the two variables.

Secondly, we can explain this result from the perspective of self-esteem. Previous studies have shown a negative correlation between envy and self-esteem [67,68]; people generate envy because of an upward social comparison and this threatens their self-esteem. In addition, prior studies have shown that self-esteem and psychological resilience are positively correlated [69]. Therefore, in the process of upward social comparison, when people feel envy, their self-esteem will be threatened which will negatively impact on their psychological resilience.

The mediating effect of psychological resilience and social support

In addition, based on Model 1, we found that social support and psychological resilience have significant mediating effects between envy and depression, which verified hypothesis 3. Meanwhile, this result also verified the resilience framework. When people face negative experiences, their external support environment interacts with their internal psychological resilience to determine their ability to adapt to the negative experience [32]. Firstly, we shall explain the mediating role of social support between envy and depression. Social support is a supportive resource or supportive behavior, and people who have a good social support system can better maintain a positive emotional experience [39]. Therefore, people with high envy may perceive less supportive resources or supportive behavior, which in turn increases the tendency to experience depression. Secondly, we explained the mediating role of psychological resilience between envy and depression. Our research showed that envy was negatively correlated with psychological resilience. In addition, the higher the level of psychological resilience, the more positive emotions and strategies of coping with stress the individual has [70,71], thus inhibiting the tendency to experience depression. Therefore, people with high envy levels are less likely to adopt positive coping styles, increasing their likelihood of suffering from depression.

Interestingly, based on these two mediation relationships, we also found two other significant mediation relationships in Model 1: 1) envy → social support → psychological resilience; 2) social support → psychological resilience → depression. The results showed firstly that envy decreased psychological resilience through decreasing social support, and secondly that lower levels of social support increased depression tendency through decreasing psychological resilience. Firstly, we explained the mediating role of social support between envy and psychological resilience. Previous studies have shown that the core characteristic of envy is social pain [72] and it is difficult for people with higher levels of envy to feel social support [16,73]. In addition, prior studies have shown that social support is positively correlated with psychological resilience [49,50]. Therefore, high envy people feel as though they receive less social support, which in turn inhibits their level of psychological resilience. Secondly, we explain the mediating role of psychological resilience between social support and depression, which confirms findings from prior studies [17]. This finding may be attributed to the fact that low social support will lead to less supportive resources and behaviors [39], so that people recover from stress more slowly, in turn decreasing their level of psychological resilience, thus enhancing depression [74]. Based on the above analysis, we combined the results of two significant mediations to obtain a comprehensive path: envy → social support → psychological resilience → depression, which confirmed both hypothesis 4 and the resilience framework [32]. That is to say, the higher the individual’s level of envy, the lower their level of social support which can decrease their psychological resilience by lowering their perceived supportive resources and behaviors, thereby indirectly enhancing their depression.

Gender differences

In addition, tests of gender differences showed that the psychological resilience level of men was slightly higher than that of women, while the social support level of women was higher than that of men, which was consistent with the results of previous research. Previous studies have shown that men show higher levels of psychological resilience than women [75,76]. This may be due to the fact that men were more accepting of themselves and those positive tendencies can translate into psychological resilience in their daily life. Likewise, many studies have shown that women have higher levels of social support than men, which may be due to the fact that women have larger and more intimate social networks [16,77,78].

Moreover, gender differences are also reflected in the structural paths: 1) envy → psychological resilience shows that compared with men, women with a high level of envy and a lower level of psychological resilience. The reason for those may be that women have higher levels of envy [16] and are less likely to recover from adversity and stress, so their level of psychological resilience is lower than that of men [75,76]. 2) social support → psychological resilience shows that compared with men, women have higher level of social support and psychological resilience. Based on gender role theory, women tend to be more compassionate and exhibit more supportive behaviors [79], so when confronted with adversities and stress, women tend to adopt positive coping styles, so their level of psychological resilience is higher.

Limitations and future directions

There are some limitations on this study. Firstly, the sample of our study is Chinese college students. Therefore, the findings of this study may not be extended to other groups. Secondly, the gender distribution of the participants was imbalanced. Although we have conducted a cross gender model analysis, future research should pay attention to ensuring gender balance. What’s more, our research uses a self-reporting method, but it has some shortcomings. This method is relatively subjective and prone to personal bias. In the future, experimental methods can be used to explore the relationship between envy and depression and its explanation mechanism.

Remarkably, previous studies have argued that envy can be divided into benign/malicious envy [10]. According to the nature of envy’s motivation, individuals with benign envy will motivate them to improve their position, thereby narrow the difference between themselves and the envied [10,80,81]. While individuals with malicious envy have a downward motivation, which makes it possible to destroy the advantages of the envied [10,80,82,83]. In addition, there are differences between the two types of envy in emotional feelings and specific behavioral tendencies [10,80]. Individuals with malicious envy are tend to perceive hostility, unfairness, and have a stronger tendency to disparage others [5,81,84,85]. While individuals with benign envy show willing to be close to envied person and tend to have positive thoughts about them [10,80]. Therefore, it is necessary for future studies to further explore the relationship between benign/malicious envy and depression and its mechanism. To further expands the understanding of the formation mechanism of depression from the perspective of benign/malicious envy.

Social implications

The findings of this study have some social implications. Firstly, the current study points out a personality variable, disposition envy, which affects depression, so as to expand the explanation mechanism of depression. Secondly, the current study reveal for the first time that we can intervene the influence of envy on depression from the perspectives of social support and psychological resilience, and then expand the resilience framework theory. Meanwhile, it also provides a new practical perspective of the prevention and correction of depression.

In conclusion, the present study is the first to prove the mediating mechanisms of social support and psychological resilience between envy and depression, based on the resilience framework. The results showed that envy affects depression in multiple ways. Firstly, envy directly affects individuals’ social support and psychological resilience which then impacts their depression. Secondly, envy indirectly affects psychological resilience by affecting social support, which in turn thus indirectly affects depression. Therefore, our study not only provides theoretical support for inhibiting individuals’ depression by promoting their social support and psychological resilience, but also has important significance for extending the resilience framework theory.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the project by Hunan Province Philosophy and Social Science Project (18YBA324, Project Name: The Personality Basis of Social Aggression and the Regulation Mechanism of Benign/Malicious Envy).

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Study design: Yanhui Xiang. Date analysis: Xia Dong. Paper writing: Xia Dong. Paper revising: all authors.