|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 9(3); 2012 > Article |

Abstract

Objective

As the number of North Korean adolescent refugees drastically increased in South Korea, there is a growing interest in them. Our study was conducted to evaluate the mental health of the North Korean adolescent refugees residing in South Korea.

Methods

The subjects of this study were 102 North Korean adolescent refugees in Hangyeore middle and high School, the public educational institution for the North Korean adolescent refugees residing in South Korea, and 766 general adolescents in the same region. The Korean version of Child Behavior Check List (K-CBCL) standardized in South Korea was employed as the mental health evaluation tool.

Results

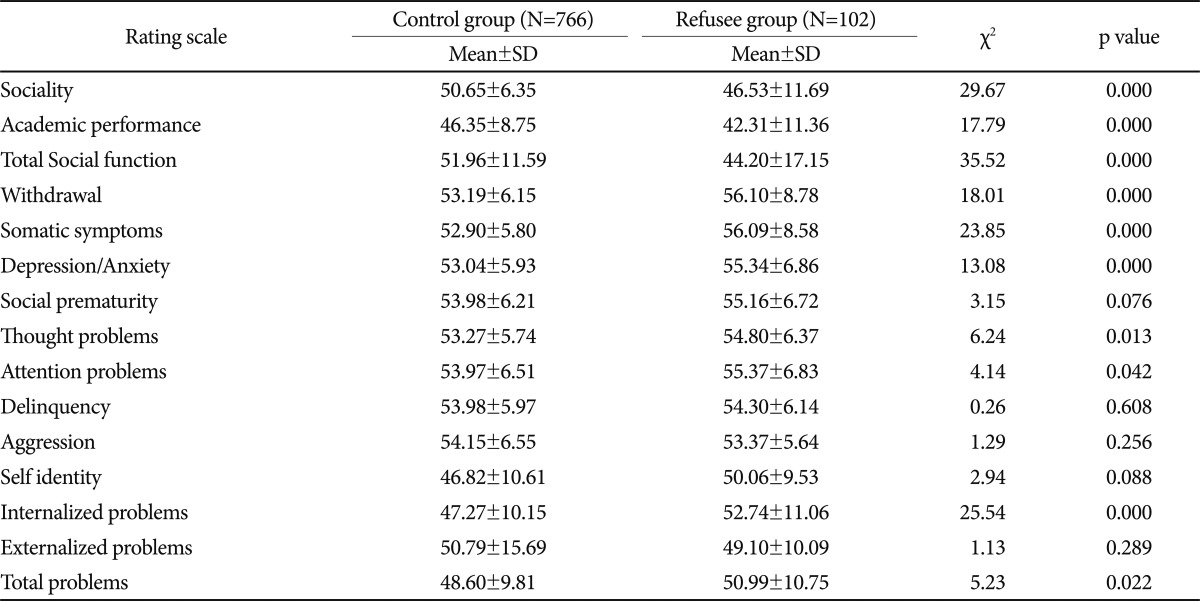

The adolescent refugees group showed a significantly different score with that of the normal control group in the K-CBCL subscales for sociality (t=29.67, p=0.000), academic performance (t=17.79, p=0.000), total social function (t=35.52, p=0.000), social withdrawal (t=18.01, p=0.000), somatic symptoms (t=28.85, p=0.000), depression/anxiety (t=13.08, p=0.000), thought problems (t=6.24, p=0.013), attention problems (t=4.14, p=0.042), internalized problems (t=26.54, p=0.000) and total problems (t=5.23, p=0.022).

Conclusion

The mental health of the North Korean adolescent refugees was severe particularly in internalized problems when compared with that of the general adolescents in South Korea. This result indicates the need for interest in not only the behavior of the North Korean adolescent refugees but also their emotional problem.

Rough estimates by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) suggest that by the end of 2006, there were approximately 9.9 million refugees and 744,000 asylum-seekers in the world of which children, young people, and adolescents constituted nearly one-quarter.1 As the number of North Korean adolescent refugees drastically increased in South Korea, there is a growing interest in them. There have been many changes in the quantity and quality of the North Korean refugees entering North Korea since middle of 1990's. There has been a dramatic increase in number as more than 1,000 North Korean refugees have entered into South Korea every year since 2002, and the total number of North Korean refugees became over 19,000 in June, 2010. Most of the North Korean refugees were defecting soldiers before, but more common North Korean people entered into South Korea after 1990's.2 Almost all the North Korean refugees entering into South Korea were at the age of twenties before 1990's and there were few adolescents and old ones. Later, the ratio of women, children and adolescents has been increased as more refugee families fled North Korea.2 North Korean adolescent refugees refer to the adolescents among the "persons who have their residence, lineal ascendants and descendants, spouses, work places, etc. in North Korea, and who have not acquired any foreign nationality after escaping from North Korea" in the article 2, paragraph 1 of the Act on the Protection and Settlement Support of Residents Escaping from North Korea.2 Nearly one-quarter of the refugees worldwide are children and adolescents.3 The number of North Korean adolescent refugees has been greatly increased: the number of children and adolescents under the age 19 who entered into South Korea is 3,013 as of August, 2010, accounting for about 16% of the total North Korean refugees.2 Up to now, the governmental policy for the support of the North Korean refugees has been focused on the health of adults. However, as the number of the North Korean adolescent refugees is increasing, the policy to support them needs to be intensified.2 Furthermore, adolescence is the period when not only the social adaptation stress but also the difficulty in identity should be overcome. In general, children and adolescents are vulnerable to not only physical damage but also stress more than adults. Since their average life expectancy is long, the complication of stress may be prolonged and severe.4

Stress and psychiatric problems as well as socioeconomic problems have been known to be an important issue to the refugees and immigrants. A few domestic studies have been reported on the stress and psychological problems in the North Korean adolescent refugees,5 the past researches in other countries on mental health of refugees showed us diverse results.6,7 About 40% of refugees showed psychiatric disorders, there were posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety disorder, conduct disorder, substance abuse, etc.8 In addition, in some researches, it was reported that young refugees showed somatic complaints, sleep problems, conduct problems, social withdrawal, attention problems, generalized fear, overdependence, restlessness and, irritability, as well as difficulties in peer relationships, etc.9,10 There was a report that in case of young refugees, the risk of psychosis was increasing11 and there was also a report that learning disabilities and developmental disorder were occurred.12 The foreign reports on refugees of children and adolescents were reported mainly in Europe. Until now, there were foreign reports on adolescent refugees from Chile, the Middle East, Yugoslavia, and Bosnia, etc.3 Hjern et al.13 performed a clinical evaluation on 50 children fled from Chile to seek refuge. It was reported that among these, 72% of children suffered from the persecution-related experiences and also showed the sleep disturbance. In a research report targeting 341 adolescent refugees from the Middle East, Montgomery14 reported that 77% of them showed anxiety, sleep disturbance and depressive symptoms. Recently, Goldin et al.15 performed the clinical measures and clinical evaluation like CBCL, targeting 48 refugees of children and adolescents (7-20 age) from Bosnia who settled down in Sweden in 1994 to 1995. As a result, it was reported that in case of 6 children among 18 adolescents in the age of 13-20, emotional and conduct problems demanding clinical attention were observed and among 18 adolescent, symptom of depression was represented as 28%, anxiety-regression as 10%, mental and physical symptom as 10%, hyperactivity as 18%, compulsion as 10%, etc. respectively. In South Korea, Jeon et al.16 reported the result of personality characteristics evaluation with 62 North Korean adult refugees using the traumatic experience and personality assessment inventory (PAI). However, there has been no study on the evaluation of the psychiatric characteristics of the North Korean children and adolescents until now. On the contrary, there was also a report representing that adolescent refugees showed the better psychiatric state, compared to the general public comparison group.17-19 Rousseau et al.19 performed the cohort study three times with the intervals of 2 years since 1994, respectively, using the method of Youth Self Report, targeting 67 Cambodian adolescent refugees residing in Canada. It was reported that as a result, a meaningful difference in the internalizing score was represented in both girls and boys as time passes while a meaningful difference in the externalizing score was not represented.

In our study, the psychiatric characteristics of 102 students in the middle and high school for the North Korean adolescent refugees located in Gyeonggi-do and 766 general students in the control group were compared using the K-CBCL standardized in South Korea.

The subjects of this study were 102 North Korean adolescent refugees in Hangyeore middle school, located in Anseong city, Gyeonggi-do, for the refugee group, and 766 middle school students in Anseong city for the control group. An epidemiological questionnaire and a child behavior checklist were used for the study with the subjects. Each subject and his or her caregivers were provided adequate counseling on the study and the associated investigations. Informed consent was obtained prior to study entry. The study was also approved by the hospital ethics committee.

The epidemiological questionnaire contained basic questions about sex, age, grade, duration of stay in South Korea, and living with parents or relatives.

Oh et al.20,21 translated and standardized the child behavior checklist developed by Achenbach into the Korean version. The criteria developed in 1991 are for the children and adolescent between the ages of 4 and 18. The problematic syndrome scale contains three internalized problems scales (withdrawal, somatic symptom, and depression/anxiety) and two externalized problems scales (delinquency and aggressiveness) as well as social immaturity, thought problem and attention problem. The individual questions were operationally defined by three-point Likert scale composed of three scores including 'Not True (0),' 'Somewhat (1) or Sometimes True,' and 'Very True or Often True (2).' Twelve scales are presented including the sex problem scale and total problem behavior scale. The sociality scale is composed of four scales including the social activity scale, sociality scale, school performance scale and total sociality scale. The withdrawal scale evaluates social shrinking, withdrawal and passive attitude. The somatic complaint scale evaluates the degree of somatic symptoms without medical symptoms. The anxiety/depression scale evaluates emotional depression, too much anxiety and degree of depressiveness. The social immaturity scale evaluates developmental problems such as acts too young for his/her age and the socially immature and unsociable aspects. The thought problem scale evaluates unrealistic and grotesque thoughts and the related behavior. The attention problem scale evaluates attention problems such as lack of attention, restless action and hyperactivity and the related behavioral problems. The delinquent behavior scale evaluates delinquent behavior such as company with bad friends, lying and runaway from home. The aggressive behavior scale evaluates aggressiveness, fight and rebellious acts. The sex problem scale evaluates the problem behavior such as too much touching of genital organs and too much thought on sex. In the study by Oh et al.3 to investigate the effective division points for the individual scales, 70T was considered to be an appropriate division point for the eight problem behavior scales but 63T (90%) was recommended as the most effective division point to evaluate problem behavior if 70T is determined as the division point for the internalized, externalized and total problems behavior scales.

The data were processed using SPSS 12.0 Korean version. If needed for statistical analysis, a cross-tabulation analysis was performed with the epidemiological questionnaire evaluation results. An ANCOVA corrected according to the age and sex of the subjects was performed for the K-CBCL. The case with p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

The sample consisted 102 refugees adolescents (34 boys and 68 girls; age 13-22 years; mean±SD 16.39±2.36) and 766 control adolescents (247 boys and 519 girls; age 11-17 years; mean±SD 13.07±1.63), The mean duration of stay in South Korea was 16.77±12.68 months (3-76 months), the mean numbers of living with parents or relatives was 1.00±0.93 years (0-4)(Table 1).

The adolescent refugees group showed a significantly different score with that of the normal control group in the K-CBCL subscales for sociality (t=29.67, p=0.000), academic performance (t=17.79, p=0.000), total social function (t=35.52, p=0.000), social withdrawal (t=18.01, p=0.000), somatic symptoms (t=28.85, p=0.000), depression/anxiety (t=13.08, p= 0.000), thought problems (t=6.24, p=0.013), attention problems (t=4.14, p=0.042) ), internalized problems (t=26.54, p= 0.000) and total problems (t=5.23, p=0.022)(Table 2).

Although South Korean adolescents may have a lot of different types of environmental stressors that North Korean adolescents do not experience, stress from academic demands, the difference of poverty and wealth, and peer pressure as bullying etc., North Korean adolescent refugees have severe traumatic experiences such as escape in a dangerous situation and stay in an extremely deteriorated refugee camp, sometime observing death, being directly tortured or raped, and witnessing their family members to be cruelly treated.22 Moreover, the North Korean adolescent refugees frequently had the experience of losing someone or something familiar with them such as loss of their family, and various characteristics that make the adaptation to a new settlement difficult.5 They received a psychological shock during their life as refugees by the breakup of family or other experiences, suffered from cold and hunger, and were not given normal education while staying long in boring refugee camps. Even in the new settlement, they have to live with the adults showing anxiety and the antisocial adult group.4 According to the study on the evaluation of the psychological state of the immigrant adolescents from individual countries in the U.S., the adolescent refugees from Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia showed a lower level of self-esteem and a higher level of depression when compared with the adolescent refugees from Latin America and Europe except Cuba and Mexico.23 Our study is assumed that the North Korean adolescent refugees may have more affective problems than the European adolescent refugees who attend a school as the previous studies.23,7 Lee24 reported that refugee families have more mental health problems than normal families, and the children in refugee families have more physical and psychological problems than the children in general families because of the domestic violence, marital conflict and family conflict that occur frequently. As the psychological severance between the parents and children continues in this way, the children may show hyper-responsible internalized or depression and choose an alternative family such as a gang.5 In this research, too, a meaningful difference was not represented in the average value of externalizing problems while a meaningful difference was represented in the average value of internalizing problems between both groups. The result like this does not conform to the result of research by Rousseau et al.19 and Jeon,5 but conforms to the result of researches by Goldin et al.15 In addition, in this research result, it is very interesting result that there was not represented a meaningful difference between both groups in externalizing problems such as delinquency, aggression, etc. This result conforms to the result of reports presented by Goldin et al.15 that the symptoms like aggressiveness or acting-out were not represented in Parent CBCL. In past researches, Goldin et al.15 stated that externalizing problems like delinquency, etc. were reported less in children compared to teachers or parents, so this may be considered to be the reason of such result. Although this survey is also based on the result of questionnaire prepared by students, the researcher tried to reduce the wrong informant bias with performing the individual psychiatric counseling, subject to consent of each student with targeting the students who reported the problems when performing the survey through questionnaire. The result of this research may be said to show that the adolescents escaped from North Korea are experiencing more internalized problems rather than externalized problems while living in South Korea, compared to the comparison group. In this research, too, they showed more score in measures of depression/anxiety and this result conforms to the result of research made by Hodes et al.8 in the past. In addition, in this research, they showed high score in measures of learning difficulties and social dysfunction, etc. and this result conforms to the result of researches made by Mollica et al.9 and Williams et al.12 in the past. In this research result, a meaningful difference was not represented in externalized problems including conduct problems between North Korean refugee group and comparison group, and this result is different from the result of researches by Hodes et al.8 and Mollica et al.9 in the past.

The North Korean adolescent refugees seem to have relatively less cultural stress because their new settlement, South Korea, is their homeland sharing the same history and language with North Korea and the social atmosphere is relatively friendly.5 However, there is a large gap in the way of thinking and culture between North and South Korea because two generations have already passed after the division, holding different ideological systems. Particularly, the North Korean social system is unprecedentedly unique, and thus the difference between the North and South Korea may throw the North Korean adolescent refugees whose self-consciousness is being formed into confusion. Hence, the cultural and social background of the North Korean adolescent refugees should be understood and the various factors that give stress on them should be taken into consideration.5 Age is an important factor to the stress on the North Korean refugees. The study conducted by Jeon25 with the adults over the age of 21 showed that the mental health was better as the age was higher. Even though it was known that adolescents better adapt themselves to stress than adults, it should be discussed more whether the North Korean adolescent refugees actually adapt themselves better to stress than the South Korean adolescents. K-CBCL was standardized the child behavior checklist depend on sex and age by the Korean version.21 But we performed an ANCOVA corrected according to the age and sex of the K-CBCL for minimizing the bias of sex and age between control group and refuse group. In our study, the mental health of the North Korean adolescent refugees was severe particularly in internalized problems when compared with that of the general adolescents in South Korea. Additionally, discussion should be made on the factor of sex. Birman and Tyler26 studied the Jewish refugee in the former Soviet Union who immigrated to the U.S. and reported the women adapted themselves better to the American culture whereas the men adapted themselves better to the Russian culture over time. Chung27 conducted a study with the North Korean refugees and reported that the North Korean men were more conservative and more oriented to the North Korean culture than the women. The duration of stay in South Korea is also an important factor, Lee et al.28 reported that the North Korean refugees felt unfamiliar with the South Korean society in the first one or two years and got familiar from about the second year, feeling helpless at the same time. Jeon7 also reported in a study with the adult North Korean refugees that the level of adaptation was generally elevated as their duration of stay in South Korea increased. However, there was also a report that the learning ability and mental health became worse as the duration of stay increased even though the language ability was improved. 5 Most of the subjects in our study had the duration of stay in South Korea less than two years and thus they were not able to be compared with the subjects who stayed in South Korea longer than two years.

In the domestic study by Baik et al.,29 the externalized problems and the internalized psychological adaptation problems were investigated with 200 North Korean adolescent refugees living in South Korea. The factors correlated with the internalized problems of the North Korean adolescent refugees were anxiety over health, old age, more traumatic experience, guilty conscience, a low level of communication, adolescents who are not in a regular school, distant relationship with South Korean friends, many members in the family, low level of family adaptation and a high level of adaptation to the South Korean culture. However, the limitation of this study was conducted with only the North Korean adolescent refugees, not including control adolescents or adult North Korean refugees. Moreover, the range of age of the subjects was from 11 to 29, including not only the adolescents but also young adults. But our study included only the students of middle school who were attending school. Although Hangyeore Middle and High School for the subjects evaluated in our study is the only public school supported by the government, the students in this school do not represent all the North Korean adolescent refugees living in South Korea. Jeong et al.30 reported that only 38% of the North Korean adolescent refugees attend a school. It is assumed that the North Korean adolescent refugees who do not attend a school may receive more stress than the adolescent refugees who attend a school.

Although the various limitations of our study, we was first conducted to compared the mental health problems of the North Korean adolescent refugees and the control adolescents residing in South Korea by the K-CBCL standardized in South Korea. Further studies should be conducted in the future to clarify the psychiatric characteristics of the North Korean adolescent refugees by augmenting the various limitations of this study.

Acknowledgments

The present research was conducted by the research fund of Dankook University in 2010.

References

1. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2006 UNHCR Statistical Yearbook. 2007,Geneva: UNHCR.

2. Ministry of Unification. 2010 White Paper on Unification. 2010,Seoul: Ministry of Unification.

3. Bronstein I, Montgomery P. Psychological distress in refugee children: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2011;14:44-56. PMID: 21181268.

4. Kang HR. A Study of Psychosocial Adjustment of North Korean Refugee Adolescents in South Korea: Focused on Depression and Anxiety. 2007,Seoul: Myungji University Press.

5. Jeon WT. For Man's Unification. 2000,Seoul: Oreum Press.

6. Lustig SL, Kia-Keating M, Knight WG, Geltman P, Ellis H, Kinzie JD, et al. Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004;43:24-36. PMID: 14691358.

7. Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet 2005;365:1309-1314. PMID: 15823380.

8. Hodes M. Psychologically distressed refugee children in the United Kingdom. Child Psychol Psychiatry Rev 2000;5:57-68.

9. Mollica RF, Poole C, Son L, Murray CC, Tor S. Effects of war trauma on Cambodian refugee adolescents' functional health and mental health status. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:1098-1106. PMID: 9256589.

10. Tousignant M, Habimana E, Biron C, Malo C, Sidoli-LeBlanc E, Bendris N. The Quebec Adolescent Refugee Project: psychopathology and family variables in a sample from 35 nations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:1426-1432. PMID: 10560230.

11. Tolmac J, Hodes M. Ethnic variation among adolescent psychiatric inpatients with psychotic disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2004;184:428-431. PMID: 15123507.

12. Williams CL, Westermeyer J. Psychiatric problems among adolescent Southeast Asian refugees. A descriptive study. J Nerv Ment Dis 1983;171:79-85. PMID: 6822822.

13. Hjern A, Angel B, Höjer B. Persecution and behavior: a report of refugee children from Chile. Child Abuse Negl 1991;15:239-248. PMID: 2043975.

14. Montgomery E. Trauma, exile and mental health in young refugees. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2011;440:1-46. PMID: 21824118.

15. Goldin S, Hägglöf B, Levin L, Persson LA. Mental health of Bosnian refugee children: a comparison of clinician appraisal with parent, child and teacher reports. Nord J Psychiatry 2008;62:204-216. PMID: 18622884.

16. Jeon WT, Yu SE, Cho YA, Eom JS. Traumatic experiences and mental health of North Korean refugees in South Korea. Psychiatry Investig 2008;5:213-220.

17. Macksoud MS, Aber JL. The war experiences and psychosocial development of children in Lebanon. Child Dev 1996;67:70-88. PMID: 8605835.

18. Betancourt TS, Khan KT. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: protective processes and pathways to resilience. Int Rev Psychiatry 2008;20:317-328. PMID: 18569183.

19. Rousseau C, Drapeau A, Rahimi S. The complexity of trauma response: a 4-year follow-up of adolescent Cambodian refugees. Child Abuse Negl 2003;27:1277-1290. PMID: 14637302.

20. Oh KJ, Lee H. Development of Korean Child Behavior Checklist: a preliminary study. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 1990;29:452-462.

21. Oh KJ, Lee H, Hong KE, Ha EH. Korean Child Behavior Checklist. 1997,Seoul: Jungang Press.

22. Fantino AM, Colak A. Refugee children in Canada: searching for identity. Child Welfare 2001;80:587-596. PMID: 11678416.

23. Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Legacies: the Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. 2001,Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

24. Lee KY. Report on the Development of the Social Adaptation Enhancement Program in Hanawon for the North Korean Adolescent Refugee Trainees. 2000,Seoul: Ministry of Unification.

25. Jeon WT. A study on the adaptation and self-consciousness of the North Korean refugees depending on the major social background. Korean Unification Stud 1997;1:109-167.

26. Birman D, Tyler FB. Acculturation and alienation of Soviet Jewish refugees in the United States. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr 1994;120:101-115. PMID: 8174934.

27. Chung JK. Gender role characteristics and values of North Koreans: data from the North Korean refugees. Korean J Psychol Gen 2002;21:163-177.

28. Lee WY, Lee KS, Seo JJ, Cheon HJ, Choi CH. A Study of Comprehensive Policy of the Problems of North Korean Refugees. 2000,Seoul: Korean Institute for National Unification.

29. Baek HJ, Kil EB, Yoon IJ, Lee YL. A Study on the Countermeasure for North Korean Adolescent Refugees I. - Focusing on the Adaptation to the South Korean Society. 2006,Seoul: National Youth Policy Institute.

30. Chung JK, Chung BH, Yang KM. Adaptation of North Korean Adolescent Refugees to South Korean Schools. 2005,Seoul: Hanyang University Press.