Deficits in Facial Emotion Recognition in Schizophrenia: A Replication Study with Korean Subjects

Article information

Abstract

Objective

We investigated the deficit in the recognition of facial emotions in a sample of medicated, stable Korean patients with schizophrenia using Korean facial emotion pictures and examined whether the possible impairments would corroborate previous findings.

Methods

Fifty-five patients with schizophrenia and 62 healthy control subjects completed the Facial Affect Identification Test with a new set of 44 colored photographs of Korean faces including the six universal emotions as well as neutral faces.

Results

Korean patients with schizophrenia showed impairments in the recognition of sad, fearful, and angry faces [F(1,114)=6.26, p=0.014; F(1,114)=6.18, p=0.014; F(1,114)=9.28, p=0.003, respectively], but their accuracy was no different from that of controls in the recognition of happy emotions. Higher total and three subscale scores of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) correlated with worse performance on both angry and neutral faces. Correct responses on happy stimuli were negatively correlated with negative symptom scores of the PANSS. Patients with schizophrenia also exhibited different patterns of misidentification relative to normal controls.

Conclusion

These findings were consistent with previous studies carried out with different ethnic groups, suggesting cross-cultural similarities in facial recognition impairment in schizophrenia.

INTRODUCTION

Impaired recognition of facial affect in schizophrenia has been documented extensively.1,2 Specifically, rather than a general deficit that encompasses all emotions, schizophrenia may be associated with a more specific deficit in the processing of a subset of negative emotions.3 For example, individuals with schizophrenia showed normal performance in the recognition of happy faces, but they were significantly impaired in the recognition of anger, sadness, and fear.4-6 Relationships between this deficit and clinical variables have been reported, including schizophrenia subtypes7 and symptoms,7-10 and cognitive8,11 and social functioning.12

Although schizophrenia appears quite to be similar across a range of cultures, cross-cultural variability has been noted.13 There have been a few cross-cultural studies of facial emotion recognition comparing schizophrenia patients and normal controls.3,14-16 Brekke et al.14 reported that Caucasians with schizophrenia performed better on a facial emotion perception task than did African-American and Latino patients. Similarly, Habel et al.15 used stimuli consisting of Caucasian faces and found that face discrimination performance was impaired across patient groups (Americans, Germans, and Indians), but was most impaired among those of Indian origin. Matsumoto16 also showed that healthy Japanese subjects performed worse in the identification of Caucasian facial emotions than healthy American subjects did in the identification of Japanese facial emotions. More recently, Pinkham et al.,17 using both Caucasian and African-American faces as stimuli, demonstrated the other-race effect, namely that participants with schizophrenia were more likely to recognize same-race faces than other-race faces. However, the majority of the studies have focused on Caucasian samples using only Caucasian faces as stimuli, and culture or ethnic-specific data on facial emotion recognition, especially in schizophrenia, are still scarce.

Although several studies in Korea have also investigated the ability to recognize facial emotion in schizophrenia, using either non-Korean or less well-validated facial stimuli, these researchers did not fully demonstrate the same-race effect.18,19 Moreover, Biehl et al.20 reported that different Asian ethnic groups showed differences in the recognition of facial expression, suggesting that grouping the countries according to a Western/Non-Western dichotomy was not justified.

The most widely used facial stimuli for evaluating emotion recognition performance were developed by Ekman and Friesen.21 Because their facial pictures did not include Asian faces, causing some restriction in ethnicity, Matsumoto and Ekman22 developed a set of facial emotion stimuli consisting of an equal number of Caucasian and Japanese faces. In Korea, our group has developed and standardized a new set of 44 colored photographs of Korean faces, called the Facial Affect Identification Test (FAIT), which includes the six universal emotions as well as neutral faces.23 The mean concurrent validity for each emotion ranged from 76% to 99%, except for the emotions of disgust and panic.

In the present study, we investigated deficits in the recognition of facial emotions in a sample of medicated, stable Korean patients with schizophrenia using Korean facial emotion pictures and examined whether the possible impairments would corroborate previous findings. Specifically, neutral faces were included to see if patients with schizophrenia misidentified neutral cues as unpleasant or threatening relative to normal controls.

METHODS

Subjects

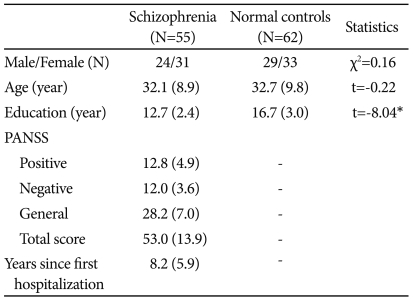

Fifty-five patients with schizophrenia (24 men, 31 women) were recruited from Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital and Kyungpook National University Hospital, and 62 healthy control subjects (29 men, 33 women) were recruited from community settings. After receiving a complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyungpook National University Hospital.

Patients were clinically stable in- or out-patients without prominent positive symptoms at the time of the study. The diagnosis of schizophrenia was established by experienced psychiatrists according to the DSM-IV. Detailed chart reviews were conducted to rule out patients with mental retardation, with a history of substance use disorder, and with any neurologic and medical disorders known to influencing cognitive functioning.

Regarding antipsychotic medications, 49 patients were taking stable regimens of atypical antipsychotics (amisulpride, aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone), and six were taking stable regimens of typical antipsychotics (haloperidol or fluphenazine) at therapeutic dosages. Healthy participants were recruited from staff members in the two hospitals mentioned above. Subjects were screened for psychotic, mood, and substance use disorders as well as for a history of head injury with significant loss of consciousness (greater than 5 min) or neurological disorder.

Demographic data for both groups and symptom characteristics of the schizophrenic patients are shown in Table 1. The two groups did not differ significantly in terms of sex and age, but years of education were significantly lower for patients with schizophrenia than for normal controls. Assessment of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) at the time of testing revealed low levels of positive and negative psychotic symptoms and general psychopathology in patients as shown in (Table 1).

Facial Affect Identification Test

FAIT is a computerized test that uses ChaeLee Korean facial expressions of emotions including happiness, sadness, fear, anger, disgust, surprise, and neutral as stimuli. Methods of its development and validation were reported elsewhere.23 Briefly, three professional actors and three actresses participated in the development. They were asked to pose each of the following facial expressions: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, disgust, and surprise. To validate the identifiability of the intended emotion, hundreds of photographs were presented to five healthy raters, and 44 of these were finally chosen on the basis of the consistency of judgments. Following that, the validity of photographs was tested by 100 individuals.

In the current study, subjects were given an explanation regarding each emotion and had two practice sessions before the FAIT began. Then, subjects were asked to choose one of six emotions or a neutral expression while viewing the facial images. A total of 44 facial images displaying happy, sad, fearful, angry, surprised, disgusted, or neutral expressions were then presented: seven faces expressed surprise and disgust, and six faces expressed the other emotions and neutral expressions. Hence, the maximum score was either six or seven according to the number of facial images presented for each emotion. The order of stimuli was randomized. The choices were displayed on the screen along with the stimuli, and subjects responded by pressing the touch screen.

Data analysis

The chi-square test (gender) and the t-test (age, education) were used to compare demographic characteristics between the schizophrenia and normal control groups. For the analysis of between-group differences on the FAIT, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used for overall correct responses, with education as a covariate, and multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used for each emotion, with education as a covariate. Analysis of the total mean response time as well as the mean response time to an individual emotion was carried out in the same manner. Pearson's correlations were performed to detect the relationship between psychiatric symptoms and performance on the FAIT in the schizophrenia group. Fisher's exact test was also used to compare error patterns between the two groups.

Data were analyzed using PASW Statistics, version 18 (SPSS, Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA). The significance level was established at 0.05.

RESULTS

Emotion recognition

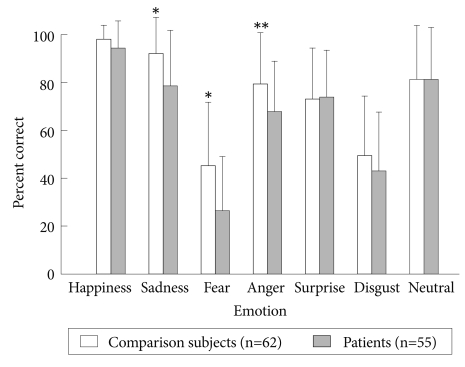

The ANCOVA, with education as a covariate, revealed that patients with schizophrenia (29.2±4.9) correctly identified the overall emotion of facial stimuli less often than did controls (32.5±3.7) [F(1,114)=6.33, p=0.013]. The MANCOVA revealed that schizophrenic patients preformed worse than controls in the recognition of sadness, fear, and anger [F(1,114)=6.26, p=0.014; F(1,114)=6.18, p=0.014; F(1,114)=9.28, p=0.003, respectively](Figure 1).

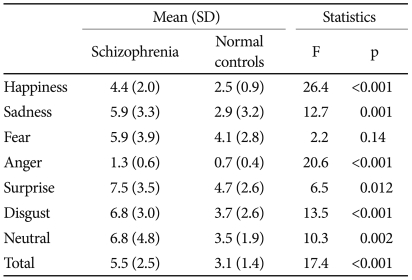

Response time

Schizophrenic patients showed significantly longer overall mean response times to facial stimuli than did controls (5.50±2.5 sec for schizophrenic patients; 3.10±1.4 sec for controls) [F(1,114)=17.38, p<0.001]. Relative to healthy participants, schizophrenic patients showed a delayed response to all emotional and neutral faces, except fearful faces (Table 2). Note that the response time of participants as a whole varied across emotions from 1.01±0.6 for anger to 6.01±3.3 for surprise.

Relationship between the emotion recognition performance and clinical variables

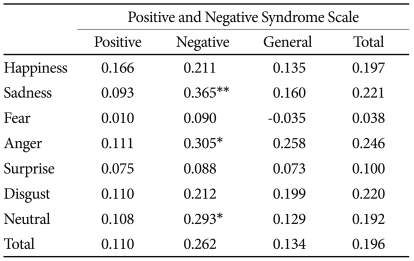

The correlations between correct response on the FAIT and symptom severity were significant for the total score as well as the three subscale scores of the PANSS. Within emotions, higher total and three subscale scores of the PANSS correlated with worse performance on both angry and neutral faces. The correct responses on the happy stimuli were negatively correlated with negative symptoms on the PANSS. However, only the correlation between angry faces and the PANSS was significant when the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied [α-adjusted p level=0.0018 (0.05/28)](Table 3).

Relationships between psychiatric symptoms and correct response of facial recognition test within schizophrenia group (N=55)

No significant correlations between the mean overall response time on the FAIT and the total as well as three subscale scores of the PANSS were found. However, the correlation between the overall response time and negative symptoms reached significance (r=0.262, p=0.053). Within emotions, higher negative subscale scores on the PANSS were correlated with longer response times for sad, angry, and neutral faces. However, the correlations were not significant when the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied [α-adjusted p level=0.0018 (0.05/28)](Table 4).

Relationships between psychiatric symptoms and response time of facial recognition test within schizophrenia group (N=55)

Duration of illness was not correlated with total correct response (r=-0.038, p=0.545) or with response time (r=0.136, p=0.323).

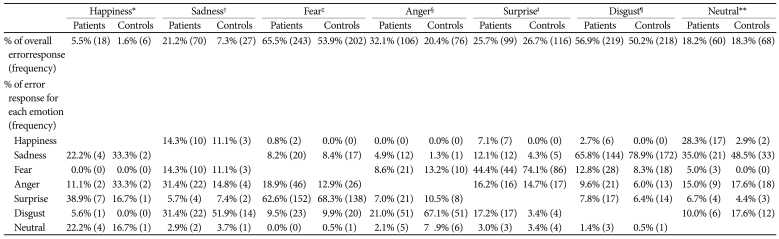

Pattern of error rates

We found that schizophrenic patients and healthy subjects differed in the distribution of errors for angry (p=0.014), surprised (p<0.001), disgusted (p=0.012), and neutral expressions (p<0.001; all by Fisher's exact test). In general, whereas error responses in healthy participants were related to one prominent emotion, those in schizophrenic patients were relatively divergent. Schizophrenic patients were less likely to attribute disgust to angry expressions (21% for schizophrenic patients compared with 67% for healthy subjects), fearful to surprised expressions (46% versus 74% respectively) and sadness to disgusted expressions (66% versus 79% respectively) compared with normal controls. Interestingly, schizophrenic patients were more likely to attribute happiness to neutral expressions (28% versus 3% respectively) than were controls. In both groups, sad faces were most commonly misrecognized as disgusted, followed by misrecognizing angry expressions. Fearful faces were most commonly misrecognized as surprised, followed by misrecognizing angry expressions. Angry faces were most commonly misrecognized as disgusted, followed by misrecognizing fearful expressions. Surprised faces were most commonly misrecognized as fearful, followed by misrecognizing angry expressions. Disgusted faces were most commonly misrecognized as sad, followed by misrecognizing fearful expressions. Neutral faces were most commonly misrecognized as sad expressions (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Impaired recognition of facial affect in schizophrenia has been investigated extensively. However, few studies have used color photographs of Korean faces with moderate sample size to investigate these impairments among Korean patients with schizophrenia. In this study, Korean patients with schizophrenia showed impairments in the recognition of sad, fearful, and angry faces, but they were as accurate as controls in the recognition of happy emotions. Patients with schizophrenia also exhibited different patterns of misidentification relative to normal controls. These findings were consistent with previous studies carried out with different ethnic groups, suggesting cross-cultural similarities in the impairment of facial recognition in schizophrenia.

Schizophrenic patients in this study were found to be less accurate in the recognition of sad, fearful, and angry facial expressions. Note that these results were obtained regardless of the inherent difficulties of the given emotion. For example, the correct response rate for sad expressions was 93%, whereas that for fearful expressions was just below 50% even in normal controls. These rates corroborated our initial validation study23 and Japanese data.16,22-24 On the other hand, schizophrenic patients did not differ from controls in recognizing happy (positive emotion) as well as surprise and disgusted expressions (negative emotions). Although it has been debated,25,26 our findings support the emotion-specific-impairment view in schizophrenia, which postulates a greater deficit for negative emotions and, furthermore, more specific deficits in the processing of a subset of negative emotions.4-6

As to our result showing a trend toward an association between response time and negative symptoms, delayed response times in schizophrenia can be accounted for by many confounding factors such as negative symptoms, persistent illness, medication induced movement disorders, and impaired general cognitive functioning.27 However, these findings might also reflect these patients' difficulties in recognizing facial emotions. In particular, the mean response time for the recognition of the fearful faces was not significantly different between the two groups not because schizophrenic patients responded as rapidly as normal controls, but because normal controls exhibited delayed responses as did schizophrenia patients due to higher difficulty of recognizing the fearful faces.

With regard to the correlations between recognition and symptoms, worse performance on the facial emotion recognition test was associated with more severe symptoms, exhibiting a stronger relationship with negative symptom scores. A large body of previous literature, mostly using the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, has indicated that negative symptoms affect the performance of facial emotion recognition in schizophrenic patients.3,6,8,9 Some studies reported a correlation between emotion recognition and positive symptoms.7,8 These mixed findings may partly depend on the clinical status of patients with schizophrenia. Although one study observed that patients with acute schizophrenia were more impaired in emotion recognition compared with normal subjects and with patients with schizophrenia in remission, most studies have been conducted with chronic and/or clinically stable patients.28 In the present study, emotional faces (i.e., happy, angry) as well as neutral faces were correlated with symptoms, which has implications for understanding symptoms in schizophrenia. Specifically, patients with schizophrenia frequently misidentify other's facial emotion in acute stage of their illness.9,29 Interestingly, difficulties in identifying happy emotions were related to the severity of negative symptoms. This evidence may support an inability to experience pleasure in activities, or anhedonia, in schizophrenia.30 Analysis of the patterns of error revealed consistent patterns in the misidentification of different emotional valences regardless of participant group. These observations were consistent with the study by Phillips et al.,31 who reported surprise as the most common misidentification of fear, anger as the most common misidentification of disgust, and disgust as the most common misidentification of anger. Further findings were also confirmed by Johnston et al.'s meticulous research reporting confusions between neutral and sad expressions.25 In general, the two groups differed in the patterns of error such that patients with schizophrenia showed more random distributions of errors than did normal controls. In this study, significant between-group differences in the pattern of erroneous misattributions were found not only for neutral faces, but also for expressions of anger, surprise, and disgust. These findings suggests that misattribution of facial emotion may not be limited to neutral expressions.

In this study, schizophrenic patients misidentified neutral cues as emotional, showing a negative as well as positive bias. Kohler et al.9 reported that patients with schizophrenia showed negative bias to neutral faces relative to controls, whereas Leppänen et al.3 found that patients exhibited more false happy (positive) as well as angry (negative) responses to neutral faces than did controls. A possible explanation for the happy (positive) response bias among schizophrenic patients may lie in the characteristics of study participants, who suffered chronically and were prone to show irrelevant responses. However, because of the lack of previous data on the analysis of the patterns of error rates and the use of a small and varied number of facial stimuli for each emotion in this study, these findings should be interpreted cautiously.

This study has some limitations. Impaired emotion recognition in this study was limited to a group of patients with schizophrenia who were clinically stable yet chronic. The effect of medication was not controlled in this study. Previous findings regarding this issue have been inconsistent.7 Although we controlled for the level of education, cognitive functions were not well controlled using more discrete variables. One similar study indicated that the facial emotion recognition was related not to general intelligence such as intelligence quotient, but to specific cognitive functions such as perseverative error.32 Our emotion-recognition task has some shortcomings, including a relatively small number of images for each emotion and the low correction rate for disgust and surprise (47% and 43% respectively). Also, the mean response time for each emotion varied regardless of participant group, which raised the issue of whether the expressional quantity of each condition was similar. Thus, cautious interpretation of the response time as absolute values is warranted.

In conclusion, using Korean emotional faces, we found that Korean patients with schizophrenia showed impairments in emotion recognition, specifically for sad, fearful, and angry faces. They also exhibited differences in the pattern of error rates. Previous studies with other ethnic groups as well as this study suggest cross-cultural similarities in the deficit in facial recognition in schizophrenia.