Controversies Surrounding Classification of Personality Disorder

Article information

Abstract

Nowadays, it is apparent that personality disorder is a common condition. Some of the concepts of personality disorder that are currently in use are flawed and need to be revised. The aim of this article is to discuss the controversy created by the uncertainties in the current classification system and to suggest ways forward. In particular, the clinician needs to be aware of the importance of assessing personality abnormality in terms of a severity dimension, and of the ways in which such an abnormality can impact on treatments for other conditions. These changes in the notion of personality disorder are needed as, for the first time, a good evidence base is being established for potential treatments and these will be maximized if we have a classification fit for therapeutic purpose.

Introduction

Personality disorders are quite common, as epidemiological studies suggest that their prevalence varies from 5-13% of the population in the community,1 but rises to around 30% of primary care attendees2 to 40-50% of those in secondary care,3 and between 70-90% of those in tertiary psychiatric services and prisons.4,5 In the last 50 years, there has been increasing recognition that personality disorder can be described and rated reliably, despite the many imperfections in its classification. Nowadays, there is general agreement among personality disorder researchers that a fundamental change is needed in its classification. The aim of this article is to introduce advanced notions of personality disorder. For this purpose, we describe the controversy created by the uncertainties in the classification of personality disorder.

Current Classification of Personality Disorder

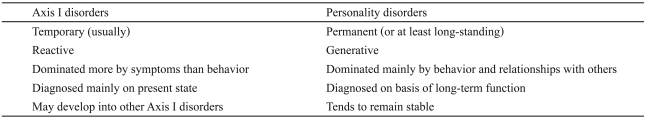

Most Korean psychiatric professionals are familiar with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) classification system.6 Although the International Classification of Disease (ICD)7 is the world classification, and therefore takes precedence over other classifications, most of the changes made in the classification of personality disorder in the last 30 years have been a direct consequence of the introduction of the third revision of DSM (DSM-III) in 1980.8 Although the individual diagnostic criteria of personality disorder are very similar in ICD-10 and DSM-IV, there is one fundamental difference between them, which is that the DSM recorded personality disorder as a separate axis of classification (Axis II) from mental state disorders (Axis I). This was quite sound at the time, because personality was considered to be in a completely different domain from that of mental state disorders. The reasons for making the separation are summarized on Table 1. One of the other reasons for separating personality and mental disorders into separate axes is that the problem of comorbidity becomes much less of a diagnostic problem once this separation is made. Subsequently, it may be appropriate to define a group of 'co-axial syndromes' in which certain Axis I disorders are found in association with Axis II disorders.9

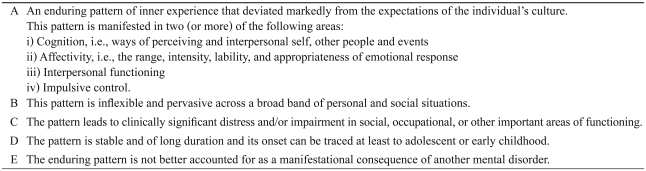

The current guidelines for the diagnosis of the personality disorder group category in ICD-10 and DSM-IV are shown in Table 2. In both classifications, the first stage is to decide whether an individual has personality disorder before deciding on his/her classification type. Both classifications are similar in that they have no mechanism for rating the severity of the personality disturbance, which makes it difficult for the clinician to plan and provide treatment.

Comorbidity of Personality Disorder with Axis I Disorders

It is becoming increasingly recognized that Axis I disorders do not encompass all syndromes with poor prognoses. The co-occurrence of Axis I disorders and Axis II personality disorder has consistently shown the worst prognosis, often approximating to the sum of the Axis-associated risks and sometimes reaching several times the risk of the Axis I disorder alone.10 Social impairment is common in patients with mental illness; however, social dysfunction that persists over time is more likely to be a consequence of personality disorder than mental illness. If clinicians were able to diagnose comorbid personality problems comprehensively, they would be able to feel confident about planning their care and predicting the outcomes of the patients with the Axis I disorders they frequently treat.

The studies undertaken to date, although having similar limitations to epidemiological researches, broadly support the conclusion that the outcome in Axis I disorders is poorer when a personality pathology is present.11 When adolescent personality disorders coexist with Axis I disorders, the long-term prognosis tends to be much worse than that for Axis I disorders only.10 Other research which longitudinally examined the interaction of personality pathology and major mental illness also supports the poor outcomes in co-morbid personality disordered patients.12 Cross-sectional data has also suggested that personality disorder is associated with greater dysfunction in those with mental illnesses.13 Researchers argued that personality disorders should be recognized as risk factors in their own right for long-term dysfunction and distress.10 Previous studies do not make it clear how personality disorder acts as a diathesis under these conditions. This negative effect of personality dysfunction on the outcome of Axis I disorders may be potentially multifaceted, including such aspects as the lack of treatment directed at the personality pathology or the clinician's perception of these patients as a difficult group to manage.14

Controversies Surrounding the Classification of Personality Disorder

Controversy 1. Is personality disorder best classified as categories or dimensions?

The DSM classification has been used to define the behavioral elements of personality disorder since DSM-III.8 Although this categorical approach is appropriate for depression and schizophrenia, it is not suitable for personality disorder, due to its heterogeneous description.15 When all of the operational criteria of personality disorder were assessed carefully, it was found that their distribution was quite unlike that of DSM.16 The other major problem with classifying personality disorder into categories is that most people with this condition qualify for more than one category. In order for the classification systems themselves to be well integrated and coordinated with basic science research on general personality structure, it is necessary for them to be closely coordinated with the classification of personality disorder in people with normal personality traits.17 The alternative of a dimensional system views personality as a continuum and, in this system, personality disorder shows the same pattern of distribution as a normal personality. The dimensional system existed before the introduction of DSM-III and has since been revised and reformulated many times,18-21 but is only now beginning to show realistic potential for widespread adoption in clinical psychiatry. Thus, it is realistic to examine both the dimensional and categorical approaches to personality disorders in the current situation,17,20,22 and the grading of severity is valuable in practice and also helps to accommodate the large number of patients who are diagnosed with unspecified personality disorders.

Controversy 2. Which personality variables should be assessed in the assessment of personality disorder?

There continues to be some debate as to which personality variables should be assessed to make a diagnosis of personality disorder in the normal/abnormal personality continuum.19,21,23-26 It would seem to be appropriate in this approach to choose those personality variables more likely to be personal and concerned with functioning, in order to assist in understanding the patient's disabilities and obtain strong clues about them. The difficulties encountered in the diagnosis and study of personality disorder include inconsistencies in assessment across both instruments and raters. The cross-instrument reliability between self-report and interview assessments in personality disorders is remarkably poor (kappa=0.27)27 and this poor agreement may explain why the research results cannot be replicated, despite the fact that the groups carry the same diagnostic label. The instrument of choice in assessing personality disorder is the structured interview schedules, mainly because their reliability and differing types of validity are superior to those of questionnaires. There are more than 10 personality interview schedules currently in use and more are being developed.22,28-30 The earliest is the Personality Assessment Schedule (PAS) developed in 1976 and since revised.31 PAS identifies 24 dimensions of personality traits/characteristics that were commonly found in personality disorder and determines to what extent they can be grouped together in terms of both their nature and severity. The value of written records describing the patient's attitudes and habitual behavior has rarely been fully appreciated. Additional information derived from the records is almost certainly critical, and this method of assessment is more helpful than other methodologies.32 A document-derived version drawn from the PAS (the Schedule for Personality Assessment from Notes and Documents: SPAN-DOC)15 has been developed with a similar underlying structure. The personality traits investigated in SPAN-DOC are classified into 26 dimensions and rated on a nine-point scale, which produces the following categories: sociopathic, explosive, passive-dependent, anankastic, schizoind, sensitive-aggressive, histrionic, asthenic, anxious, paranoid, hypochondriacal, dysthymic, and avoidant. In Table 3, there is a comparison between the 18 scale items of the Dimensional Assessment of the Personality Pathology-Basic Questionnaire (DAPP-BQ)33 derived from the 282 self-report items and the 26 traits rated by SPAN-DOC. Despite the fact that they were derived from different sources, there is a high degree of commonality between the two systems that supports the notion that they are measuring the same basic constructs.

Controversy 3. Is diagnosis of personality disorder stable?

Though the definitive feature of personality disorder in the DSM classification is that it is 'pervasive', it now looks as through this definition is incorrect. There is abundant evidence that personality traits are unstable,34-38 and there is also evidence for greater stability of social dysfunction in long-term studies.36,39 Whereas in the past this lack of stability was regarded as a contaminating effect of mental state or a poor assessing instrument, the growing evidence that it seems to be universal has prompted a change of view. Thus, only personality function, rather than disorder, can be accurately assessed at any point in time. In a longitudinal study, all four personality disorders (borderline, schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive) showed similar improvements after 2 years, with the highest rate of remission being 61% in schizotypal personality disorder and the lowest 50% in avoidant personality disorder.37,40 However, in studies using a self-rated instrument for dependent personality, dependent personality features showed high stability.41 There is also evidence from epidemiological studies that cluster A pathology persists into older age.42

Fortunately, a consistent finding from studies on the treatment of personality disorder is that, both in the short and longer term, those patients who present themselves for the treatment of their personality disorders show a steady improvement.34,36,37,43-45 This improvement is generally greater for those with borderline personality disorder than for those with other disorders.

Controversy 4. Can personality disorder be graded by severity?

It has become increasingly clear that some form of severity assessment is necessary to decide on the priorities to use for the management of personality disorder. The notion of severe personality disorder is central to much of the work in the area of forensic psychiatry. What is clear from empirical research studies is that those with more severe personality disorder do not have stronger manifestations of one single disorder as often postulated,46 but instead their personality disturbance extends across all domains of personality.46-48 Although severity is not normally taken into account when classifying mental illness, it is important in personality disorders, as normal personality and personality disorder are both on the same continuum. Unfortunately, there is no measure of severity for personality disorder in the DSM or ICD classification, and the absence of these measures is of significant concern. Indeed, treatment is justified when it is likely to ameliorate distressing or disabling syndromes, even when the patients fail to meet the full diagnostic criteria of psychiatric disorders and, consequently, the measure of severity is highly relevant to the planning and provision of treatment. A reliable way of assessing personality disorder is to use 3 levels of severity (Table 4). By using this measure of severity, it is possible to use the cluster system to get a measure of severity and this measure is also relevant in assessing those with the most severe personality disorders in forensic psychiatry.

Research on Personality Disorder in Korea

Personality disorder is now being accepted as an important condition in mainstream psychiatry throughout the world. Recently, this disorder has become more prominent in the international research literature.15 In Korea, however, there have been few studies on personality disorder.

We searched for articles on personality disorder in the official journals of the national psychiatric associations covering general psychiatry in the Republic of Korea, United Kingdom, and United States of America, for the quantitative analysis of research on this subject. The selected journals are the Psychiatry Investigation (PI) for the Korean Neuropsychiatric Association, the British Journal of Psychiatry (BJP) for the Royal College of Psychiatrists, and the American Journal of Psychiatry (AJP) for the American Psychiatric Association. In addition, we searched for articles on personality disorder originating from Korea published in internationally cited (SCI) psychiatric journals. Articles were searched for using the ISI Web of Science electronic databases and the official websites for each journal in the past 3 years (January 2007 to December 2009), and the search keyword term was PERSONALITY DISORDER. Two of the journals (BJP, AJP) were monthly publications, while the other journal (PI) was published biannually until 2008 and quarterly from 2009. The results revealed that no article concerning personality disorder was to be found in a search of 48 articles in the 8 issues of PI (except for 3 articles on traits/character/temperaments), whereas the BJP and AJP had published similar amounts of articles on this subject. The BJP published 29 empirical research articles on personality disorder in 409 original research articles during this time (7.1%). The AJP published 25 articles on personality disorders in 350 original research articles during this time (7.1%). In addition, there was only 1 article concerning personality disorder originating from Korea published in the cited international journals during this period (except for 7 articles on traits/character/temperaments). This lack of data on personality disorder could be due to the lack of research sources and little funding available in Korea. These findings might also reflect the fact that many researchers view it as unimportant.

Evidence for Treatment of Personality Disorder

One of the difficulties with personality disorder has been its treatment-resistant feature and enduring problematic behavior. Most patients with personality disorder do not desire treatment and are therefore considered as treatment resisting (Type R), whereas less than one in three patients with a personality disorder are treatment seeking (Type S).49 Usually, sufferers from personality disorder show a lack of awareness of the consequences of their behavior and frequently remain indifferent or blame others for the distress caused by their actions and interactions. Nidotherapy, in which the environment is changed, rather than the patient, may be suitable for the Type S majority.50-52

The reason that personality disorder is taken more seriously these days is that some effective treatments for the condition now exist.53 Although most patients with personality disorder do not desire treatment, a growing body of literature supports the view that patients who seek treatment for personality disorders show a steady improvement, both in the short and long term.36,39 Table 5 summarizes the treatments that have been tested adequately according to the tenets of evidence based medicine. No specific preferences are given in Table 3, but the evidence is summarized.

Conclusions

Personality disorders represent one of the major unresolved areas of psychiatry in Korea. Their important contribution to functional impairment has been largely ignored and their impact on the outcome of Axis I disorders has remained undetected in this country. Nowadays, we have better knowledge of their nature and course and are beginning to find ways to alter their core features. New treatments are now beginning to emerge which show evidence of efficacy and it is not unreasonable to hope that, in the near future, personality disorder will be better recognized and defined, able to be exposed without misunderstanding, and managed appropriately and well.

Acknowledgments

Professor Peter Tyrer is the Chair of the WPA section on Personality Disorders. This work was supported by a Korea Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2009-013-E00019) and the Research and Scholarship Foundation in 2009.