1. Endler NS, Parker JDA. Assessment of multidimensional coping: task, Emotion, and avoidance strategies. Psychol Assess 1994;6:50-60.

2. Billings AG, Moos RH. The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. J Behav Med 1981;4:139-157. PMID:

7321033.

3. Campbell-Sills L, Cohan SL, Stein MB. Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behav Res Ther 2006;44:585-599. PMID:

15998508.

4. McWilliams LA, Cox BJ, Enns MW. Use of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations in a clinically depressed sample: factor structure, personality correlates, and prediction of distress. J Clin Psychol 2003;59:423-437. PMID:

12652635.

5. Lam D, Schuck N, Smith N, Farmer A, Checkley S. Response style, interpersonal difficulties and social functioning in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2003;75:279-283. PMID:

12880940.

6. Li Z, Zhang J. Coping skills, mental disorders, and suicide among rural youths in China. J Nerv Ment Dis 2012;200:885-890. PMID:

22986278.

7. Billings AG, Moos RH. Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with unipolar depression. J Pers Soc Psychol 1984;46:877-891. PMID:

6737198.

8. Christensen MV, Kessing LV. Clinical use of coping in affective disorder, a critical review of the literature. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2005;1:20PMID:

16212656.

9. Havermans R, Nicolson NA, Devries MW. Daily hassles, uplifts, and time use in individuals with bipolar disorder in remission. J Nerv Ment Dis 2007;195:745-751. PMID:

17984774.

10. MacAulay R, Cohen AS. Affecting coping: does neurocognition predict approach and avoidant coping strategies within schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res 2013;209:136-141. PMID:

23680466.

11. Nagase Y, Uchiyama M, Kaneita Y, Li L, Kaji T, Takahashi S, et al. Coping strategies and their correlates with depression in the Japanese general population. Psychiatry Res 2009;168:57-66. PMID:

19450884.

12. Vinberg M, Froekjaer VG, Kessing LV. Coping styles in healthy individuals at risk of affective disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2010;198:39-44. PMID:

20061868.

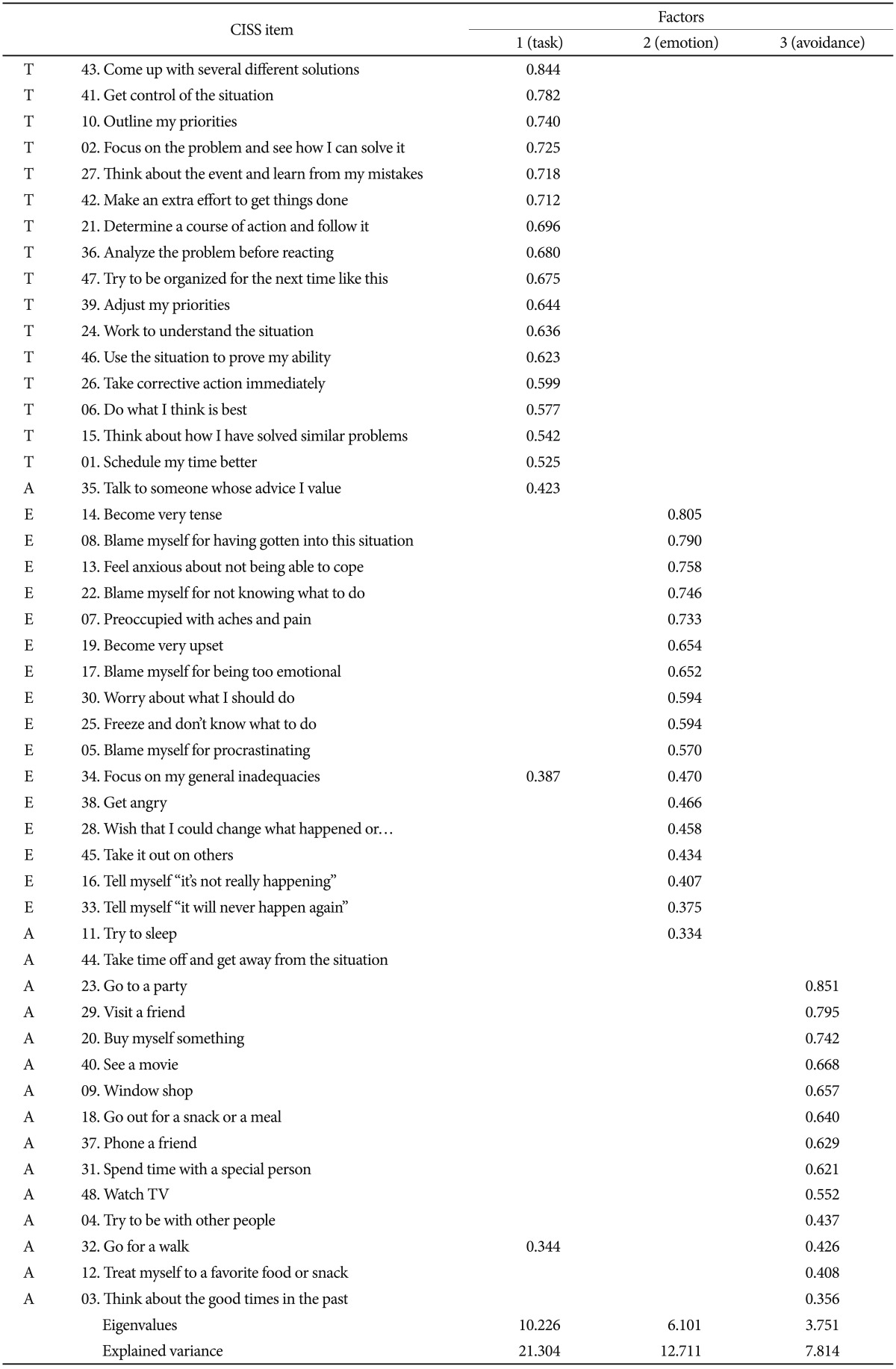

13. Endler NS, Parker JD. Multidimensional assessment of coping: a critical-evaluation. J Pers Soc Psychol 1990;58:844-854. PMID:

2348372.

14. Endler NS, Parker JD. Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS): Manual. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 1990.

15. Calsbeek H, Rijken M, Bekkers MJTM, Henegouwen GPVB, Dekker J. Coping in adolescents and young adults with chronic digestive disorders: impact on school and leisure activities. Psychol Health 2006;21:447-462.

16. Boysan M. Validity of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations-short form (CISS-21) in a non-clinical Turkish sample. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci 2012;25:101-107.

17. Sakata M, Takagishi Y, Kitamura T. Factor structure of the Japanese version of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations: reclassification of coping styles and predictive power for depressive mood. J Psychol Psychother 2013;3:111

18. Furukawa T, Suzuki-Moor A, Saito Y, Hamanaka T. [Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS): a contribution to the cross-cultural studies of coping]. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 1993;95:602-620. PMID:

8234537.

19. Rafnsson FD, Smari J, Windle M, Mears SA, Endler NS. Factor structure and psychometric characteristics of the Icelandic version of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS). Pers Individ Diff 2006;40:1247-1258.

20. Ramli M, Mohd AF, Khalid Y, Rosnani S. Validation of the Bahasa Malaysia version of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situation. Malays J Psychiatry 2008;17:7-16.

21. Boysan M. Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the coping inventory for stressful situations. Arch Neuropsychiatry 2012;49:196-202.

22. Park YC, Kim KI, Noh S. Validity assessment of the CISS (coping Inventory for stressful situation) in Korean highschool students. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 2000;39:55-64.

23. Jo HI. Reliability and validity of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situation (CISS) in African American adolescents. Korean J Couns Psychother 2000;12:205-214.

24. Endler NS, Parker JD. Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS): Manual Multi-Health Systems. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 1999.

25. Johnson DL. A Compendium of Psychosocial Measures: Assessment of People with Serious Mental Illnesses in the Community. New York: Springer; 2010.

26. Jensen AR. The G Factor: the Science of Mental Ability. London: Praeger, Westport, Conn; 1998.

27. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. London: Pearson/A&B, Boston [Mass.]; 2007.

28. Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval 2005;10:1-9.

29. Cosway R, Endler NS, Sadler AJ, Deary IJ. The coping inventory for stressful situations: factorial structure and associations with personality traits and psychological health. J Appl Biobehav Res 2000;5:121-143.

30. Uehara T, Sakado K, Sakado M, Sato T, Someya T. Relationship between stress coping and personality in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychother Psychosom 1999;68:26-30. PMID:

9873239.