Relationship between Depression and Laryngopharyngeal Reflux

Article information

Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between depression, somatization, anxiety, personality, and laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR). We prospectively analyzed 231 patients with symptoms with LPR using the laryngopharyngeal reflux symptom index and the reflux finding score. Seventy nine (34.2%) patients were diagnosed with LPR. A significant correlation was detected between the presence of LPR and total scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (5.6±5.3 vs. 4.0±4.6, p=0.017) and the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (4.3±4.9 vs. 3.0±4.5, p=0.041). LPR was significantly more frequent in those with depression than in those without (45.6% vs. 27.0%, p=0.004). A multivariate analysis confirmed a significant association between the presence of LPR and depression (odds ratio, 1.068; 95% confidence interval, 1.011–1.128; p=0.019). Our preliminary results suggest that patients with LPR may need to be carefully evaluated for depression.

INTRODUCTION

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is retrograde movement of gastric contents into the larynx and pharynx leading to a variety of upper aerodigestive tract symptoms. It is estimated that 4–10% of patients presenting to otolaryngologists have LPR.12 Furthermore, 50–60% of chronic laryngitis cases and difficult-to-treat sore throats may be related to LPR.3

Many of the symptoms related to LPR are nonspecific, such as voice change, chronic throat clearing, chronic cough, globus pharyngeus, and dysphagia. Most patients complaining of these symptoms do not show specific abnormalities on a laryngeal examination.4 The most commonly reported physical findings of LPR on fiberoptic endoscopy are edema and erythema of the larynx.56 At least two studies have found laryngeal abnormalities in a healthy asymptomatic population.7 The lack of definite abnormal findings accounting for these symptoms and variability of the condition suggest the possibility of an association with psychological factors.891011 These psychological factors may have an important role in the predisposition, initiation, progression, and aggravation of LPR symptoms.91011

The present study investigated the associations between depression, somatization, and anxiety and the presence of LPR in a routine clinical practice to better understand the relationships between depression, somatization, anxiety, and LPR.

METHODS

Subjects

Patients with chronic laryngeal signs and symptoms suspected to be reflux-related and who visited the Department of Otolaryngology-HNS, the Catholic University of Korea between April, 2014 and June, 2015 were assessed for study eligibility. Principal inclusion criteria included age ≥20 years, a clinical diagnosis of LPR, which was evaluated by medical history, a careful laryngoscopic examination, and a self-administered questionnaire. The institutional review board of Bucheon St. Mary's Hospital approved all protocols and the study design, and all patients gave written informed consent.

Laryngoscopy was performed by an otolaryngologist (YHJ) and interpreted by two independent otolaryngologists (YHJ and YSS). Reflux finding scores (RFS) were summed to determine the score for each of the following findings: subglottic edema (0/2), vocal fold edema (0/1/2/3/4), ventricular obliteration (0/2/4), diffuse laryngeal edema (0/1/2/3/4), erythema/hyperemia (0/2/4), posterior commissure hypertrophy (0/1/2/3/4), thick mucus (0/2), and granuloma (0/2). The reflux symptom index (RSI) is a self-administered nine-item questionnaire designed to assess various symptoms related to LPR (Table 1). Each item is rated on a scale from 0 (no problem) to 5 (severe problem), with a maximum total score of 45, indicating the most severe symptoms. LPR was defined as a RFS >7 and a RSI score >13.1213

Rating scales

This study used the following measures to investigate the associations between the presence of depression or somatization and symptom severity in patients with LPR. The Korean version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression, the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) for somatization, the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) for anxiety, and the 44-item Big Five Inventory (BFI) for personality traits.141516 The criteria for depression (PHQ-9 ≥5), anxiety (GAD-7 ≥5), and somatization (PHQ-15 ≥10) were defined as suggested by previous studies.141516 The BFI personality traits are extraversion (talkative, assertive, and energetic); agreeableness (good-natured, cooperative, altruistic, and empathic); conscientiousness (orderly, responsible, and dependable); neuroticism (neurotic, easily upset, and not self-confident); and openness (open to experience, intellectual, imaginative, and independent-minded). The BFI consists of 44 items; higher scores represent higher levels of each personality trait.17

Statistics

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, multiple logistic regression analysis, multiple linear regression analysis, and correlation analysis were used, as appropriate, to detect significant associations among the distribution of categorical values. P-values<0.05 were considered significant. Numeric data are expressed as means±standard deviations.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

A total of 231 patients participated in the study [158 (68.4%) women; mean age, 54.6 years; range, 20–78 years], and 131 (56.7%) had a RSI score >13, and 136 (58.9%) had a RFS >7. Seventy-nine patients had significant RFS and RSI score, resulting in LPR prevalence of 34.2%. No difference in LPR incidence was detected between men and women (p=0.076). Mean scores on the PHQ-9, PHQ-15, and GAD-7 were 4.6±4.9 [61.0% normal to minimal depression (n=141); 46.2% mild to severe depression (n=90)], 6.2±4.5 [19.5% normal to minimal somatic symptoms (n=45); 80.5% low to severe somatic symptoms (n=186)], and 3.4±4.7 [25.1% normal to minimal anxiety (n=58); 74.9% mild to severe anxiety (n=173)], respectively.

Relationships between LRP and depression, somatization, anxiety, and personality

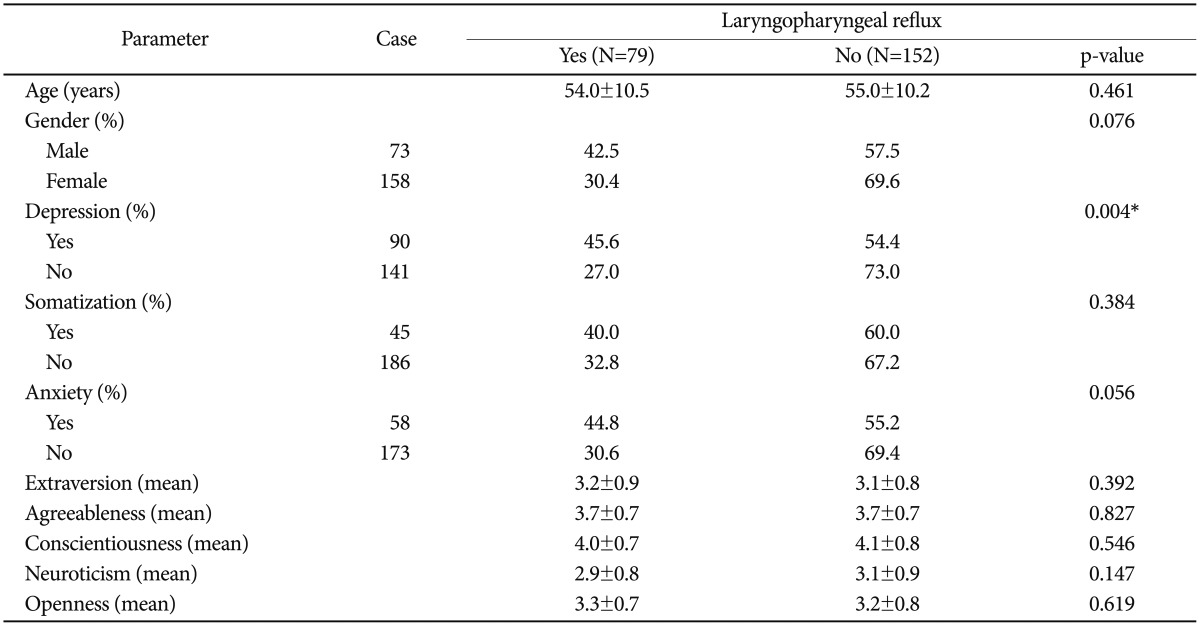

Significant correlations were detected between the presence of LPR and total scores on the PHQ-9 (p=0.017) and GAD-7 (p=0.041). Mean total scores on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 in cases with LPR were 5.6±5.3 and 4.3±4.9, respectively, whereas those without LPR had mean total scores on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 of 4.0±4.6 and 3.0±4.5, respectively. A marginally significant correlation was observed between the presence of LPR and total PHQ-15 score (p=0.051). The presence of LPR was significantly different between those with and without depression, as defined by total PHQ-9 score (p=0.004). However, no differences in the presence of LPR were observed between those with and without somatization, anxiety, or personality traits (Table 1). A multivariate Cox regression analysis confirmed a significant association between the presence of LPR and the PHQ-9 (odds ratio, 1.068; 95% confidence interval, 1.011–1.128; p=0.019).

DISCUSSION

LPR-related symptoms are commonly presented to otolaryngologists. Some authors have reported that 10% of patients presenting have LPR.18 Kamani et al.19 estimated that the prevalence of LPR symptoms in the UK population was 34.4%. Globus sensation, throat clearing, cough, and other nonspecific symptoms are different presentations that may be related to LPR. The most commonly reported physical findings of LPR on fiberoptic endoscopy are edema and erythema of the larynx.620 At least two studies have found that laryngeal abnormalities are detectable in the healthy asymptomatic population.2122 The inconsistent findings related to presentation of LPR and uncertainty of the etiological background of these presentations suggests a possible association between these presentations and psychological problems.23

Many studies have evaluated the psychological influence in patients with non-specific upper aerodigestive tract symptoms, particularly globus. Globus has been thought to be a definite hysterical symptom, as it is strongly associated with depressive illness responds well to antidepressant therapy.10 Park et al.24 reported that patients with globus tended to have somatization regardless of LPR but patients without reflux reveal significantly higher scores on all other symptom dimensions of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised. Globus symptoms in men indicate a much more profound psychological problem than those in women with the same complaint.11 Barofsky et al.25 also observed a group of patients who complain of swallowing difficulties but who have normal pharyngeal function following radiological and psychological evaluations but have clinically significant psychological characteristics. However, studies investigating the relationship between LPR and psychological factors are rare. A recent cohort study found that one-third of patients with LPR suffer from anxiety and significantly reduced social activities compared with those in controls.26 However, in other studies, patients with LPR did not demonstrate any psychological distress.2728 Mesallam et al.28 reported that the psychological background of patients with LPR does not affect the patients' self-perception of their reflux-related problem. Chronic laryngeal signs and symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) are often referred to as LPR or reflux laryngitis. LPR is an extraesophageal variant of GERD, because the main symptomatic region involves the laryngopharynx. The relationship between psychological distress and GERD is complex and poorly defined. GERD may contribute to psychological distress, and in fact, psychological distress may contribute more significantly to poor quality of life than do symptoms. In a meta-analysis by El-Serag, persistent GERD symptoms despite medical treatment were associated with decreased psychological and physical well-being.29 van der Velden et al.30 found that subjects with residual GERD symptoms had an odds ratio of 2.8 and 3.2 for anxiety and depression, respectively.

We provide evidence suggesting that a significant portion of patients with LPR may struggle with symptoms of depression during the clinical course of their disorder. In the present study, the mild to severe depression rate was 46.2% (90 of 231). In addition, 41 (51.9%) of our 79 patients with LPR had depression, whereas only 49 (32.2%) of the 152 patients without LPR had depression. This finding suggests that patients with LPR may suffer from a broad range of clinical manifestations of depression. These are the first data supporting a substantial influence of depression on LPR. These results may help clinicians understand the role of depression as a potential moderator in the clinical manifestation of LPR.

The limitations of this study include the following. First, the study cohort was small, leading to large standard deviations. Second, we did not consider other psychiatric comorbidities. Third, no formal diagnosis of depression was made by structured interview. Future studies employing prospective, randomized methods to examine the psychological problems in patients with LPR are warranted.

In conclusion, the present study preliminarily demonstrates that clinicians may need to carefully evaluate depression to properly management patients with LPR. Subsequent adequately-powered studies with a better design will be crucial to validate and support our preliminary findings.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment: This study was supported by a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI12C0003).