Comparative Study of the Efficacy and Side Effects of Brand-Name and Generic Clozapine for Long-Term Maintenance Treatment Among Korean Patients With Schizophrenia: A Retrospective Naturalistic Mirror-Image Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Clozapine is considered the most reliable drug for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. In 2014, a generic formulation of clozapine (Clzapine) was introduced in Korea. This study was performed to provide clinical information regarding the use of clozapine and to compare efficacy and tolerability when converting from the brand-name formulation (Clozaril) to the generic formulation during longterm maintenance treatment among Korean patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

This mirror-image study retrospectively investigated the electronic medical records of patients who had switched from Clozaril to Clzapine with a ≥1-year duration for each formulation. Clinical data were collected, including information regarding clozapine use, psychiatric hospitalization, co-medications, and blood test findings. Data before and after the switch were compared using paired t-tests.

Results

Among 332 patients, the mean 1-year dosages were 233.32±149.35 mg/day for Clozaril and 217.36±136.66 mg/day for Clzapine. The mean clozapine concentration-to-dose ratios were similar before and after the switch (Clozaril, 1.33±0.68; Clzapine, 1.26±0.80). Switching from Clozaril to Clzapine resulted in no significant differences in the hospitalization rate, hospitalization duration, or laboratory findings (liver function parameters, serum cholesterol level, and serum glucose level). Equivalent doses of co-prescribed antidepressants were decreased, but concomitant medications otherwise showed no significant differences.

Conclusion

Clinical efficacy and tolerability appear comparable when switching to Clzapine during clozapine maintenance treatment. This study offers descriptive real-world clinical insights into clozapine maintenance treatment in Korea, thereby providing patients with more treatment options and contributing to the development of maintenance guidelines tailored to the Korean population.

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a complex neuropsychiatric disorder involving positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms. The prevalence of schizophrenia is approximately 1%, and 30%–60% of patients do not respond well to antipsychotic medications [1]. For these patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, clozapine is considered a standard treatment [2].

Clozapine was first commercially introduced in Switzerland and Austria in 1972 . In 1975, it was banned after 16 serious cases of agranulocytosis developed in Finland [3,4]. However, evidence of its outstanding treatment efficacy led to resumption of clinical studies [5-7]. One of these, the renowned study by Kane et al. [8], demonstrated the effectiveness of clozapine among patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. In 1989, clozapine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It has since remained the standard treatment option for treatment-resistant schizophrenia [9-12]. In 1995, clozapine was also approved in South Korea.

Proactive blood monitoring through the clozapine Patient Monitoring Service is conducted for early detection of hematologic adverse events, with the goal of mitigating agranulocytosis risk. However, in addition to agranulocytosis, clozapine is associated with several other important clinical side effects. Serious side effects include seizures and inflammatory conditions such as myocarditis and pneumonia [13,14]. Additionally, clozapine treatment is associated with an increased risk of metabolic syndrome, and studies have demonstrated a risk of hepatotoxicity [15-17]. Sedation, weight gain, constipation, and excessive salivation may also decrease patient compliance [9]. Nevertheless, clozapine has unique advantages that make it a favorable option for the treatment of schizophrenia. Clozapine shows excellent efficacy in alleviating both positive and negative symptoms, as well as improving social adaptation and occupational functioning [6,18,19]. Clozapine can reduce symptoms of tardive dyskinesia [20] and help prevent suicide [21].

More than 30 years have passed since the introduction of the original clozapine compound, and several generic formulations have been developed in various countries during the past few years. Considering the higher cost of brand-name clozapine compared with generics, the availability of generic clozapine is expected to reduce healthcare expenses and provide wider treatment opportunities [22,23]. In South Korea, the generic clozapine was introduced in January 2014 [24]. There are several concerns regarding generic drugs, including doubts about biological equivalence, efficacy, and tolerability [25-27]. Thus far, research generally supports the bioequivalence, effectiveness, and safety of generic clozapine among patients whose condition has been stabilized with brand-name clozapine [28-30]. However, a few case reports have suggested that the replacement of brand-name clozapine with generic clozapine may be associated with relapse or symptom exacerbation among patients with schizophrenia [31-33]. In South Korea, Woo et al. [25] compared the pharmacokinetic profiles of brand-name clozapine and generic clozapine, confirming their bioequivalence. The authors performed a randomized crossover study involving a controlled protocol, a clozapine regimen of 100 mg/day, a small sample size (n=28), and a limited study period of several days. Considering the rather serious side effects of clozapine and the high variability in drug responses and tolerability among individuals, there is a need to obtain real-world clinical data from larger sample sizes and long-term treatment courses.

In this naturalistic mirror-image study, we retrospectively investigated the treatment outcomes of generic (Clzapine, Dongwha Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea) and brand-name clozapine (Clozaril, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) using electronic medical records. The participants comprised 332 patients who were initially undergoing ≥1 year of maintenance treatment with brand-name clozapine; they subsequently switched to generic clozapine and maintained this treatment for another ≥1 year. The present study was performed to investigate the use of brand-name and generic clozapine in real-world clinical practice and to compare the efficacy and tolerability of these drugs. This study was conducted in Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH), a tertiary hospital with the highest number of clozapine prescriptions in South Korea.

METHODS

Study design

This was a retrospective, naturalistic, and observational mirror-image study based on electronic medical records at SNUH. Participant screening and data extraction were conducted using the clinical data warehouse of SNUH (SUPREME 2.0; Seoul National University Hospital Patients Research Environment). The collected data for each patient included the record of prescriptions, including clozapine; anonymized demographic information; laboratory findings; and hospitalization record. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of SNUH (IRB No. 2003-240- 1115). The IRB waived the requirement for informed consent prior to data extraction.

Study participants

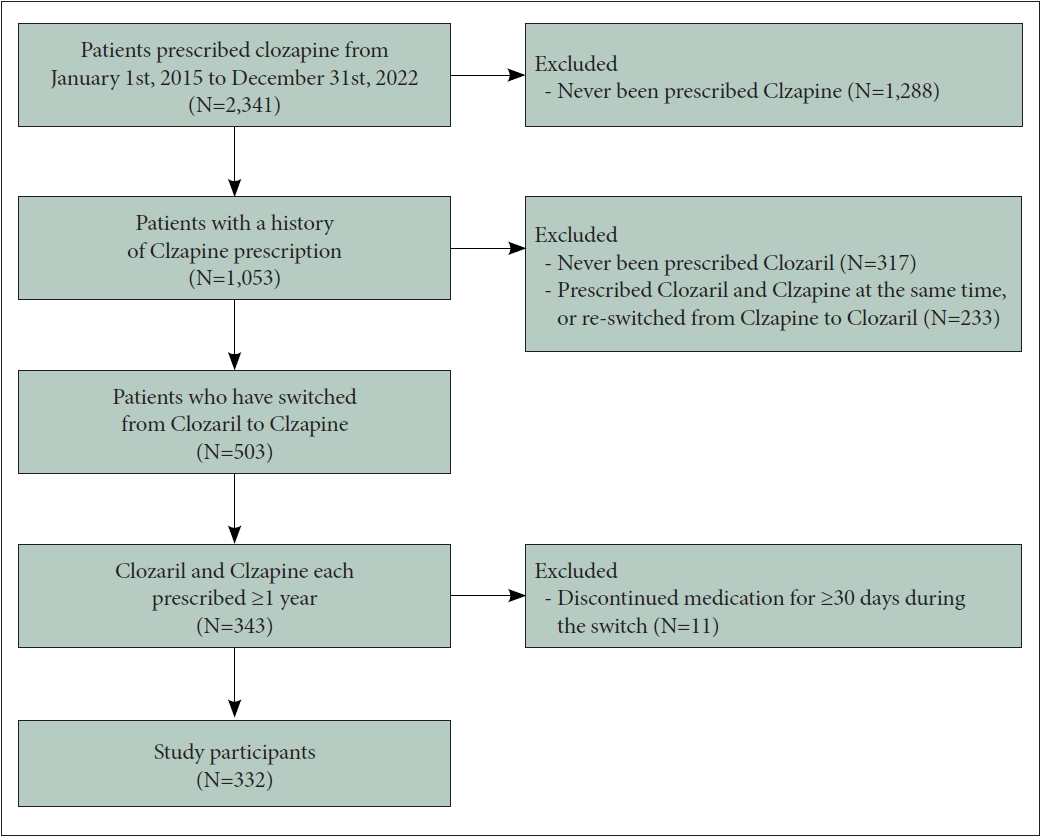

The participants comprised patients who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia in SNUH and had a history of switching from Clozaril to Clzapine during their clozapine maintenance treatment, with ≥1 year of treatment for each formulation. First, considering that Clzapine was initially introduced in SNUH in 2015, patients prescribed clozapine from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2022 were selected. In total, 2,341 patients were screened, among whom 1,053 had a prescription record of Clzapine. Among them, 736 patients had been prescribed both Clzapine and Clozaril. Patients who were co-prescribed both drugs simultaneously or re-switched from Clzapine to Clozaril were excluded (n=233), and 503 patients with a history of switching from Clozaril to Clzapine remained. Based on their prescription records, only patients who received and maintained both Clozaril and Clzapine for >1 year were selected (n=343). Patients were considered to have discontinued the medication if there was an interruption in the prescription lasting ≥30 days; such patients were excluded from the study. Patients were also excluded from the study if the interval between switching from Clozaril to Clzapine was ≥30 days (n=11). The final study population comprised 332 patients who, during the maintenance period of clozapine therapy, had used Clozaril for ≥1 year and subsequently switched to Clzapine, maintaining it for another ≥1 year (Figure 1).

Data assessment and time points of data collection

We investigated the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, such as sex and age. The mean duration of Clozaril and Clzapine maintenance was also examined. For each formulation, the endpoint clozapine dosage within the treatment period was identified. Because the total treatment duration for each formulation varied among patients, the reference period of 1 year before and after the switch point (from Clozaril to Clzapine) was used for the comparison. For Clozaril, the last prescription immediately before the switch point was used, and for Clzapine, the last prescription within 1 year from the switch point was used. For patients who underwent measurement of the clozapine plasma concentration during this period, the concentration-to-dose ratio (C/D ratio) of clozapine was calculated via division of the steady-state clozapine plasma concentration by the daily dosage. However, the trough level could not be assessed.

We also examined and compared the 1-year treatment outcomes of Clozaril and Clzapine maintenance treatment. Parameters included concomitant psychotropic medications (co-prescribed antipsychotics other than clozapine, mood stabilizers, and antidepressants), psychiatric hospitalization, and laboratory findings related to adverse reactions. Among patients taking concomitant medications, we investigated the types, number, and doses at the endpoint prescription for each formulation. Equivalent doses were calculated for antipsychotics (olanzapine-equivalent dose) [34,35] and antidepressants (fluoxetine-equivalent dose) [36].

To examine the long-term outcomes of Clozaril and Clzapine, the number and duration of psychiatric hospitalizations within the 1-year reference period for each formulation were compared. Additionally, the serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), cholesterol, and glucose were examined to assess serologic parameters related to the side effects of clozapine. However, there was inconsistency in the timing and frequency of measurements among patients: some underwent repeated blood tests, some underwent only one test, some underwent only glucose measurements, and some underwent none of the above-mentioned blood tests. Consequently, each laboratory finding had a different sample size. For Clozaril, the most recent value before the switch point was used, and for Clzapine, the value measured closest to the endpoint of the 1-year treatment period was used (Figure 2).

Schematic description of time points for laboratory tests during treatment with brand-name clozapine (Clozaril) and generic clozapine (Clzapine). Representative example of blood sample selection for the analysis before and after switching from Clozaril to Clzapine. Durations of Clozaril and Clzapine prescription are each depicted as yellow and orange boxes. Red dots indicate dates on which blood samples were collected. Red arrows indicate blood samples selected and included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Paired t-tests were used to compare demographic and clinical variables between periods of Clozaril and Clzapine treatment within the same patients. Descriptive statistics are presented as means±standard deviations. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A significance threshold of p<0.05 was used for two-tailed tests.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The 332 patients in this study comprised 168 (50.6%) male and 164 (49.4%) female. Their mean age at the time of switching from Clozaril to Clzapine was 43.17±13.04 years. At that time point, 197 (59.3%) patients were taking at least one concurrent antipsychotic, 165 (49.7%) patients were taking concurrent antidepressants, and 83 (25.0%) patients were taking concurrent mood stabilizers. The mean duration of Clozaril treatment was 1,788.98±523.84 days, and the mean duration of Clzapine treatment was 792.67±142.74 days (Table 1).

Clozapine maintenance treatment

The endpoint dosage of clozapine within the reference period was used for analysis because it was assumed most likely to represent the 1-year maintenance dose of clozapine. Overall, the mean clozapine dosage was 225.34±143.26 mg/day (range, 12.5–900 mg/day). Almost half of the patients were using clozapine at a dosage range of 200–450 mg/day (47.4%), and a substantial proportion of them were using the standard dosage or less: very low (<150 mg/day), 32.7%; low (150–300 mg/day), 34.5%; and standard (300–600 mg/day), 31.3%.37 The mean dosage of Clozaril during the maintenance period was 233.32±149.35 mg/day, whereas the mean dosage of Clzapine during the treatment period was significantly lower at 217.36±136.66 mg/day (t=3.975, p<0.001) (Table 2). Despite the statistically significant difference, the dose distribution of each formulation was similar (Figure 3).

Clozapine dose and C/D ratio for brand-name clozapine (Clozaril) and generic clozapine (Clzapine) treatment periods

Clozapine dose distribution change from brand-name clozapine (Clozaril) to generic clozapine (Clzapine). Split violin plot showing the distribution of endpoint clozapine dosage during each reference period. Dotted lines indicate mean values for Clozaril and Clzapine, respectively. N, number of patients (total=332).

Among all patients, 64 underwent measurement of the serum clozapine concentration during both the Clozaril and Clzapine periods. The C/D ratio was calculated and compared between these patient groups; no statistically significant difference was found between the Clozaril and Clzapine treatment periods (1.33±0.68 ng/mL per mg/day vs. 1.26±0.80 ng/mL per mg/day, t= 0.756, p=0.452) (Table 2).

Psychiatric hospitalization as a treatment outcome

Among all patients, the number and duration of psychiatric hospitalizations were compared within 1 year before and after the switch from Clozaril to Clzapine. Admissions to daycare centers were excluded; only admissions to open and closed wards were included in the comparative analysis (Table 3). The mean numbers of admissions within 1 year before and after the switch from Clozaril to Clzapine were 0.08±0.37 and 0.11± 0.35, respectively; these numbers did not significantly differ (t=-1.079, p=0.281). Similarly, the mean durations of hospitalization were 2.46±11.62 days during the Clozaril treatment period and 3.35±11.92 days during the Clzapine treatment period; these numbers did not significantly differ (t=-0.946, p=0.329).

Concurrent psychotropic medication with clozapine

Concomitant psychotropic medications at the endpoint of each reference period for Clozaril and Clzapine were compared (Table 3). The mean number of antipsychotics concurrently prescribed with Clozaril was 0.77±0.77; the olanzapineequivalent dose was 8.29±10.68 mg/day. The mean number of antipsychotics concurrently prescribed with Clzapine was 0.78±0.81; the olanzapine-equivalent dose was 8.54±11.90 mg/day. These data did not exhibit a significant difference (t=-0.431, p=0.667; t=-0.630, p=0.529). The number of concurrently prescribed antidepressants did not significantly differ between the two formulations (Clozaril vs. Clzapine: 0.65±0.73 vs. 0.62±0.71, t=1.132, p=0.259). However, the fluoxetine-equivalent antidepressant dosage was significantly lower for Clzapine (24.95±39.81 mg/day) than for Clozaril (26.79±40.72 mg/day) (t=2.140, p=0.033). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the mean number of concurrently prescribed mood stabilizers between the Clozaril and Clzapine treatment periods (0.28±0.52 vs. 0.30±0.55, t=-1.000, p=0.318). The concomitant medications, along with their names and number of patients, are listed in Supplementary Table 1 (in the online-only Data Supplement).

Laboratory test findings associated with clozapine-related side effects

To investigate blood parameters associated with clozapine-related adverse reactions, we compared the serum levels of AST, ALT, cholesterol, and glucose measured during the Clozaril and Clzapine treatment periods. The analysis included only patients who had undergone blood tests during treatment with both formulations, and the value measured closest to the endpoint of the reference period for each formulation was used for analysis (Figure 2). Different sample sizes were applied for each blood test, as indicated in Table 4.

Comparison of laboratory findings during brand-name clozapine (Clozaril) and generic clozapine (Clzapine) treatment periods

Table 4 shows a comparison of blood test results during the Clzapine and Clozaril treatment periods. With respect to liver function, 132 patients underwent measurement of AST and ALT during both treatment periods. Among these patients, there were no significant differences in the concentrations of AST (Clozaril vs. Clzapine: 25.67±21.64 IU/L vs. 24.54±19.00 IU/L, t=0.72, p=0.473) or ALT (28.98±27.67 IU/L vs. 29.14±29.65 IU/L, t=-0.108, p=0.914) between the Clozaril and Clzapine treatment periods. Among the 94 patients who underwent cholesterol measurement during treatment with both formulations, there was no significant difference between the Clozaril and the Clzapine treatment periods (179.99±41.91 mg/dL vs. 178.09±40.23 mg/dL, t=0.488, p=0.626). Among 131 patients, there was no significant difference in blood glucose concentration between the Clozaril and Clzapine treatment periods (117.6±37.5 mg/dL vs. 121.79±37.17 mg/dL, t=-1.379, p=0.170). Additionally, no cases of agranulocytosis were identified during the 2-year study period.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the clinical characteristics of clozapine by switching from brand-name clozapine, Clozaril, to generic clozapine, Clzapine, among 332 psychiatric patients who maintained each medication for ≥1 year. The mean endpoint dosages were 233 mg/day for Clozaril and 217.4 mg/day for Clzapine. The C/D ratio did not significantly differ between Clozaril and Clzapine (1.33 ng/mL per mg/day vs. 1.26 ng/mL per mg/day, t=0.756, p=0.452). Similarly, the number and duration of psychiatric hospitalizations were not significantly different between Clozaril and Clzapine treatment periods. The numbers of concurrent antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers, as well as the olanzapine-equivalent antipsychotic dosages, were also similar; however, the fluoxetine-equivalent antidepressant dosage was slightly lower for Clzapine (26.79 mg/day vs. 24.95 mg/day, t=2.140, p=0.033). Serologic outcomes including the serum AST, ALT, cholesterol, and glucose levels did not significantly differ between the two formulations. Overall, the 1-year treatment outcomes and the serologic changes associated with brand-name Clozaril and generic Clzapine were comparable. Additionally, the results demonstrate the current status of real-world clozapine use as a long-term maintenance treatment in a Korean tertiary hospital.

The current package insert for clozapine states that the target dosage for initial titration is 300–450 mg/day. However, there is no established consensus guideline regarding the maintenance dosage, and the suggested daily dosage ranges from 100 to 900 mg/day [38,39]. The general suggestion is that the maintenance dosage should be lower than the initial target dose for stabilization [11,38-40]. In this study, the mean maintenance dose of clozapine, represented as the 1-year endpoint dosage, ranged from 200 to 250 mg. According to conventional understanding, this appears to be a low dose range [37,39,40]. However, based on the previous finding that Asian patients exhibit lower clozapine clearance than Western patients [41], a study by de Leon et al. [42] showed that Asian patients require lower doses of clozapine. In a recent retrospective study of clozapine titration among Korean inpatients, the mean dosage 8 weeks after starting clozapine was 212.83 mg/day [43]. Additionally, the mean dosages were 216 mg/day in a Chinese report [44] and 186 mg/day according to the Japanese Clozaril Patient Monitoring Service database [45]. Results from an opinion survey in India [46] also demonstrated a low maintenance dosage (75–100 mg/day, 25%; 150 mg/day, 23%; 150–300 mg/day, 24%; n=117). Despite the considerable interindividual variability in clozapine metabolism and response, it appears that Asian patients with schizophrenia are using clozapine at a lower dose range for maintenance treatment.

The optimal dosage of clozapine varies according to the individual patient’s clozapine clearance, which can be assessed using the C/D ratio. Monitoring of the serum clozapine level and C/D ratio is important for predicting the patient’s response and risk of adverse events. Poor clozapine metabolizers with a high C/D ratio can reach a therapeutic clozapine level with the lowest clozapine dosage, and they may have a higher risk of dose-dependent side effects of clozapine. Recent reviews suggest that compared with Western patients, Asian patients generally show a higher C/D ratio [42,47], possibly twice as high [48], along with a higher incidence of poor drug metabolism [41]; these findings highlight the importance of a population-based approach to clozapine treatment. Despite this importance, well-controlled large-scale studies regarding the C/D ratio among Asian populations, particularly Korean populations, are limited. In a systematic review involving 876 Chinese and Korean patients, the mean C/D ratio was 1.57 ng/mL per mg/day [41]. Among 597 Korean patients with schizophrenia in a recent study, the mean C/D ratio was 1.23 ng/mL per mg/day, with a significant difference between men and women (1.11 ng/mL per mg/day vs. 1.75 ng/mL per mg/day, respectively) [43]. Despite the lack of assessment of the trough condition in the present study, the steady-state C/D ratio was evaluated among 64 patients. The mean C/D ratios were 1.33 ng/mL per mg/day for brand-name clozapine and 1.26 ng/mL per mg/day for generic clozapine; these values did not significantly differ. This result is similar to findings in a previous Korean study [43]. Further studies should include assessments of other confounding factors such as sex, smoking status, co-medications, and trough condition [42,48].

A paired t-test comparing the brand-name and generic clozapine treatment periods showed that the clozapine dosage was slightly lower after switching from brand-name Clozaril (233.32±149.35 mg/day) to generic Clzapine (217.36±136.66 mg/day, t=3.975, p<0.001). A significant time-dependent effect presumably contributed to this result. Gradual dose reduction of antipsychotics after the stabilization phase is often considered during schizophrenia maintenance treatment to minimize the risk of side effects associated with long-term use [49]. Despite the reduced clozapine dosage after switching from Clozaril to Clzapine, the C/D ratio did not significantly differ. The lack of a significant difference in C/D ratio between Clozaril and Clzapine indicates that bioequivalence of the two drugs was maintained during long-term treatment. This result is consistent with a randomized crossover study by Woo et al. [25], which demonstrated the pharmacokinetic bioequivalence of Clozaril and Clzapine. It was a short-term controlled trial of a rather small sample size (n=28) with a strictly fixed clozapine dosage (100 mg/day). However, the present study involved a real-world clinical setting with a large sample size and long-term study period. In addition, the number and duration of psychiatric hospitalizations were assessed as part of the treatment outcome evaluation. Among 332 patients, the mean number of hospitalizations was approximately 0.1 per year. During the 2-year reference period, 84.9% (n=282/332) of the patients maintained outpatient treatment and did not require hospitalization. The 1-year mean number and duration of hospitalizations did not significantly differ between the brand-name and generic clozapine treatment periods. Although individuals with no prescription history in SNUH for 30 consecutive days were excluded from the study, it must be taken into account that admission to medical center other than SNUH could not be identified.

We also found that 64.2% (n=213) of all patients undergoing clozapine maintenance treatment were concurrently taking other antipsychotic medications, 27.4% (n=91) were concurrently taking mood stabilizers, and 54.2% (n=180) were concurrently taking antidepressants. Additionally, 35.8% (n= 119) of patients used no other antipsychotics in combination, and 13.9% (n=46) of patients were undergoing clozapine monotherapy without antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, or antidepressants. These results indicate that most of the patients were undergoing polypharmacy. In previous studies concerning polypharmacy with clozapine in various countries, 10% to 80% of patients undergoing treatment with clozapine were undergoing polypharmacy with other antipsychotics [50-54]. Combination therapy involving antipsychotics with clozapine has been suggested to significantly reduce positive symptoms, improve cognitive functioning, and mitigate the long-term burden of side effects [55,56]. However, polypharmacy is also associated with increased costs and a higher risk of side effects [57]. Therefore, careful evaluation on an individual-patient basis is necessary to ensure that appropriate combination therapy is administered.

The numbers of concurrent antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers did not significantly differ after switching from brand-name clozapine to generic clozapine. Additionally, the olanzapine-equivalent dose of concurrent antipsychotics did not significantly differ, but the fluoxetine-equivalent dose of antidepressants slightly decreased. A time-dependent effect should be considered when interpreting this result. Antidepressant augmentation in the antipsychotic treatment of patients with schizophrenia is a common clinical practice to treat comorbid symptoms such as depression, anxiety, negative symptoms, or obsessive-compulsive symptoms [58]. Patients’ symptoms may stabilize over time, resulting in a decreased need for augmentation with antidepressants.

The endpoint laboratory findings, including the serum AST, ALT, cholesterol, and glucose concentrations, remained comparable before and after switching from brand-name to generic clozapine. Agranulocytosis was not observed throughout the 2-year treatment period. The limited sample size must be considered; only ~40% of the patients had recorded AST, ALT, and glucose concentrations available for comparative analysis, and only 30% of the patients had a recorded serum cholesterol concentration. Considering the long-term adverse events, annual fasting blood glucose and lipid measurements are recommended after 6 months of clozapine administration [59-61]. Further investigation with a longer study period is warranted.

Notably, although 332 patients were included in our comparative analysis, a large number of patients (1,053—constituting 45% of the total 2,341 patients undergoing clozapine treatment) had received generic clozapine at least once during their treatment. Generic drugs are chemically equivalent to brand-name drugs in that they contain the same active ingredient, and they theoretically have the same bioequivalence [62,63]. However, clozapine has a narrow therapeutic window and a relatively high rate of serious adverse reactions, making it crucial to carefully evaluate whether the drug is genuinely interchangeable without increasing patient risk in real-world clinical settings. Thus far, no studies in South Korea have investigated the long-term natural treatment course of clozapine when transitioning to a generic formulation. In this naturalistic study involving a substantial number of patients, brand-name and generic clozapine showed no significant differences in treatment outcomes or adverse effects, with the exception of a slight decrease in the doses of clozapine and concurrent antidepressants. Taken together, these findings suggest that generic clozapine is a viable option.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, it did not include an assessment of disease severity in terms of symptoms or subjective satisfaction. Second, specific data regarding the incidences of adverse events were not collected. Third, considerable differences in sample size existed with respect to the C/D ratio and laboratory findings. Fourth, as the study exclusively focused on patients who independently maintained each medication for over one year, cases where the transition to generic clozapine failed or where patients returned to brand-name clozapine within one year were not addressed. Therefore, evaluations were not conducted for patients who experienced an unsuccessful transition to generic clozapine. Lastly, limitations regarding the naturalistic retrospective study design exist. Due to the absence of a comparative arm, a direct comparison between the group continuing brand-name clozapine and the group switching from brand-name clozapine to generic clozapine was not available. Future studies should aim to address these limitations and provide a more comprehensive analysis. Nevertheless, this study provides valuable insights into the current status of clozapine use as a maintenance treatment in Korea, realistically reflecting real-world clinical practice in a Korean tertiary hospital.

In this study of Korean patients with schizophrenia undergoing long-term clozapine maintenance treatment, clozapine was generally used at a relatively low dose of 200–250 mg, and the C/D ratio was higher than the ratio reported for Western patients. Our results provide descriptive information regarding the current clinical practice of clozapine maintenance treatment in a Korean tertiary hospital. In addition, during long-term clozapine maintenance treatment for ≥2 years, brand-name clozapine and generic clozapine showed similar clinical efficacy and tolerability, supporting the non-inferiority of generic clozapine in the treatment of schizophrenia in Korea. It is important to acknowledge certain limitations in interpreting the findings, particularly with respect to the naturalistic design of the study and the absence of trough level data. Nevertheless, these results offer valuable clinical insights into the current practice of clozapine maintenance in Korea. This information may contribute to the development of maintenance guidelines tailored to the Korean population.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article athttps://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2023.0413.

Concomitant medications during Clozaril and Clzapine treatment period

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualizations: Se Hyun Kim, Minah Kim, Jun Soo Kwon. Data curation: Nuree Kang, Hee-Soo Yoon, Jae Hoon Jeong. Formal analysis: Nuree Kang, Hee-Soo Yoon, Jae Hoon Jeong, Se Hyun Kim. Investigation: all authors. Methodology: Nuree Kang, Hee-Soo Yoon, Jae Hoon Jeong. Writing—original draft: Nuree Kang, Hee-Soo Yoon, Se Hyun Kim. Writing—review & editing: Nuree Kang, Se Hyun Kim, Minah Kim, Jun Soo Kwon.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Dongwha Pharmaceuticals, and a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI22C0108).

Acknowledgements

None