|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 20(3); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objective

Methods

Results

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary┬ĀFigure┬Ā1.

Supplementary┬ĀFigure┬Ā2.

Supplementary┬ĀFigure┬Ā3.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The data underlying this study will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Minji Bang, a contributing editor of the Psychiatry Investigation, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Hyun-Ju Kim, Sang-Hyuk Lee. Formal analysis: Hyun-Ju Kim, Sang-Hyuk Lee. Funding acquisition: Sang-Hyuk Lee. Investigation: Hyun-Ju Kim, Sang-Hyuk Lee. Methodology: Chongwon Pae, Sang-Hyuk Lee. Project administration: Sang-Hyuk Lee. Resources: Hyun- Ju Kim, Sang-Hyuk Lee. Software: Hyun-Ju Kim, Sang-Hyuk Lee. Supervision: Minji Bang, Chun Il Park, Chongwon Pae, Sang-Hyuk Lee. Validation: Sang-Hyuk Lee. Visualization: Hyun-Ju Kim, Sang-Hyuk Lee. WritingŌĆöoriginal draft: Hyun-Ju Kim, Chongwon Pae, Sang-Hyuk Lee. WritingŌĆöreview & editing: all authors.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT [grant number NRF-2019M3C7A1032262], [grant number NRF-2021M3E5D9025026]. It was also funded in part by the Healthcare AI Convergence Research & Development Program through the National IT Industry Promotion Agency of Korea (NIPA), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT [grant number S0254-22-1002]. Both sets of funding were secured by S.H. Lee.

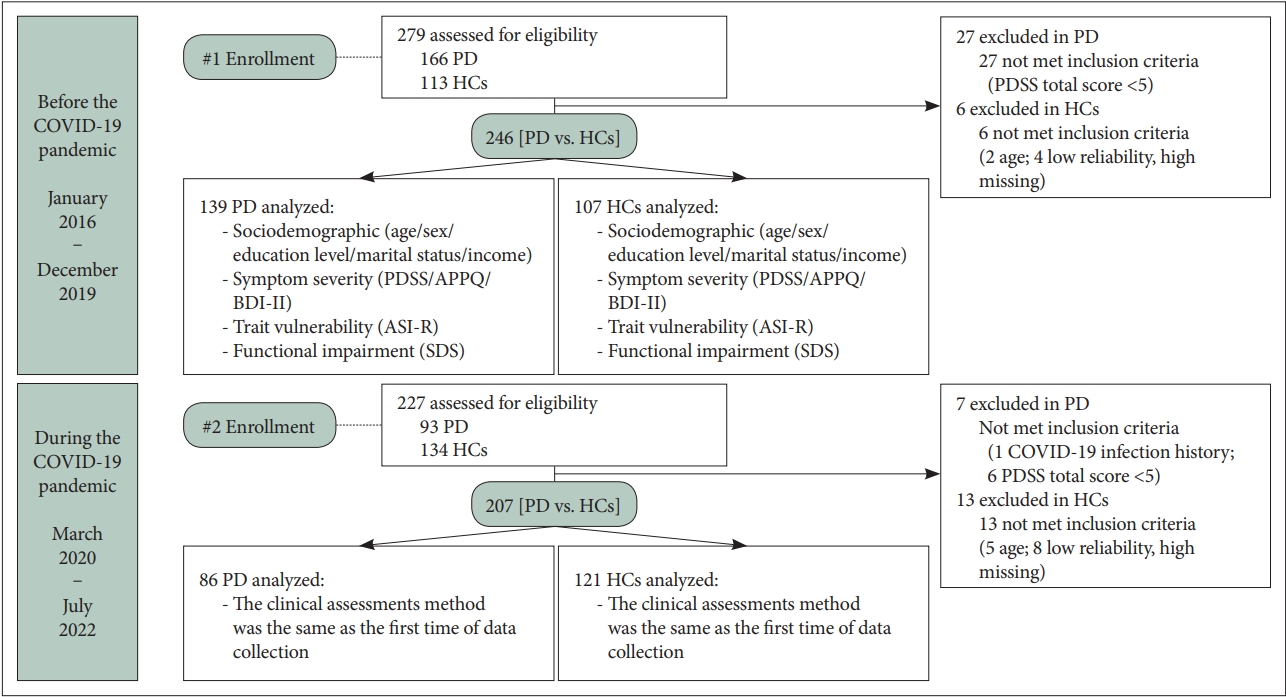

Figure┬Ā1.

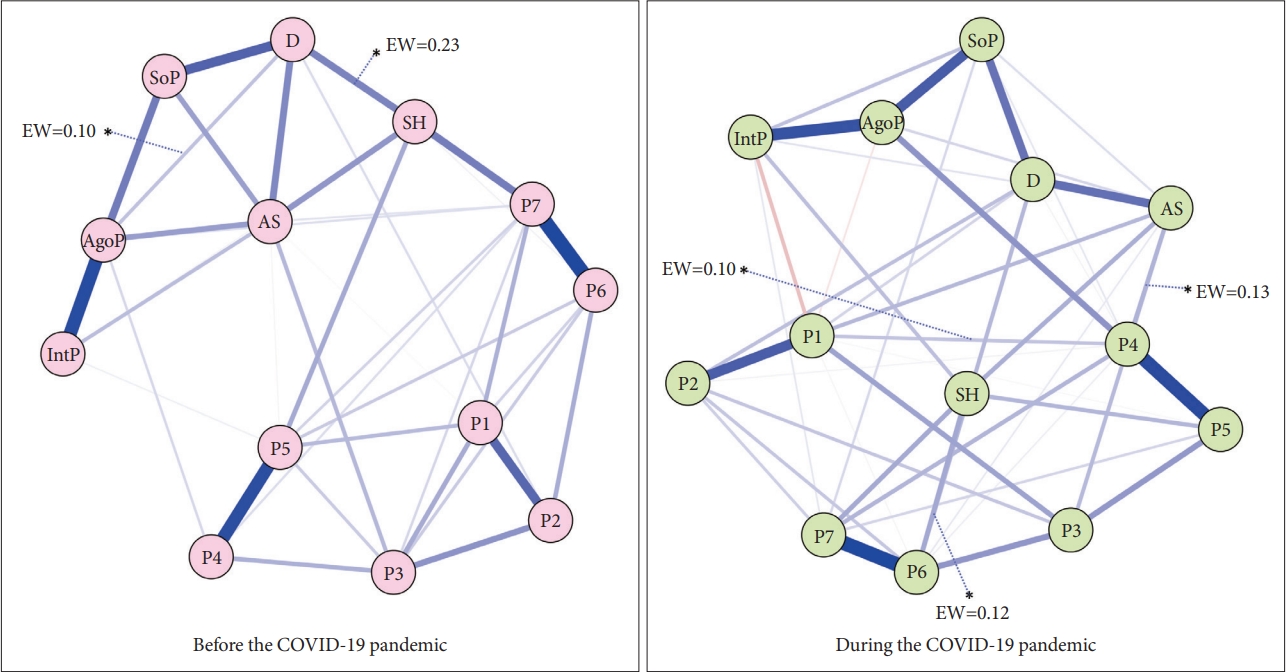

Figure┬Ā2.

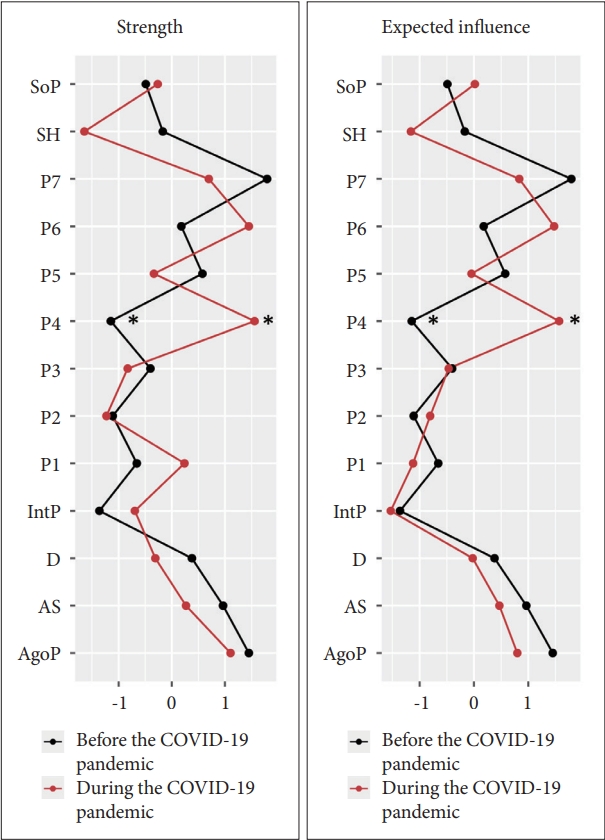

Figure┬Ā3.

Table┬Ā1.

Table┬Ā2.

| Variables |

PD (N=225) |

HCs (N=228) |

t or Žć2 | p |

Two-factor ANOVAŌĆĀ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Before COVID-19 (N=139) |

During COVID-19 (N=86) |

Before COVID-19 (N=107) |

During COVID-19 (N=121) |

Diagnosis |

COVID-19 period |

Diagnosis-by-COVID-19 interaction┬¦ |

||||||

| M┬▒SD or N (%) | M┬▒SD or N (%) | M┬▒SD or N (%) | M┬▒SD or N (%) | F | p | F | p | F | p | |||

| Age (yr) | 39.27┬▒11.34 | 38.55┬▒12.91 | 37.98┬▒11.99 | 36.14┬▒10.01 | n.a. | n.a. | 2.85 | 0.09 | 1.36 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.61 |

| Sex, male/female | 69 (49.6)/70 | 37 (43.0)/48 | 49 (48.5)/58 | 53 (43.8)/68 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.14 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.67 |

| Level of education (yr) | 14.99┬▒2.48 | 14.90┬▒1.97 | 16.84┬▒2.29 | 16.63┬▒2.28 | n.a. | n.a. | 63.69 | <0.001* | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.09 | 0.77 |

| Marital status, living without partner/with partner | 53 (38.1)/83 | 36 (41.9)/46 | 40 (39.6)/45 | 59 (48.8)/51 | n.a. | n.a. | 3.46 | 0.06 | 1.19 | 0.78 | 0.01 | 0.92 |

| Monthly income, <1,800 $USD/Ōēź1,800 $USD | 5 (4.2)/126 | 7 (7.6)/78 | 2 (2.0)/67 | 3 (2.5)/92 | n.a. | n.a. | 2.01 | 0.16 | 1.24 | 0.27 | 0.88 | 0.35 |

| Agoraphobia, yes | 63 (45.3) | 42 (48.8) | n.a. | n.a. | 0.09 | 0.77 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Duration of illness (mo) | 48.79┬▒74.20 | 31.23┬▒47.36 | n.a. | n.a. | -1.79 | 0.08 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Currently pharmacotherapy, yes | 21 (15.1) | 13 (15.1) | n.a. | n.a. | <0.001 | 0.999 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Kinds of SSRI, escitalopram/paroxetine | 7 (33.3)/10 (47.6) | 6 (46.2)/3 (23.1) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| SSRI equivalent dosage (mg)ŌĆĪ | 15.43┬▒9.25 | 16.15┬▒11.21 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.21 | 0.84 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

Table┬Ā3.

| Variables |

PD (N=225) |

HCs (N=228) |

Two-factor ANOVAŌĆĀ |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Before COVID-19 (N=139) |

During COVID-19 (N=86) |

Before COVID-19 (N=107) |

During COVID-19 (N=121) |

Diagnosis |

COVID-19 period |

Diagnosis-by-COVID-19 interactionŌĆĪ |

||||||

| M┬▒SD | M┬▒SD | M┬▒SD | M┬▒SD | F | p | F | p | F | p | |||

| Panic symptom severity | ||||||||||||

| PDSS total score | 11.12┬▒5.27 | 12.56┬▒5.79 | 0.13┬▒0.57 | 0.19┬▒0.89 | 797.73 | <0.001** | 3.27 | 0.07 | 2.76 | 0.10 | ||

| 1. Panic attack frequency | 1.54┬▒1.08 | 1.79┬▒1.19 | 0.02┬▒0.15 | 0.05┬▒0.26 | 368.98 | <0.001** | 2.70 | 0.10 | 1.74 | 0.19 | ||

| 2. Distress during panic attacks | 1.92┬▒1.16 | 2.06┬▒1.09 | 0.01┬▒0.11 | 0.04┬▒0.20 | 527.73 | <0.001** | 0.96 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.53 | ||

| 3. Severity of anticipatory anxiety | 1.91┬▒0.95 | 2.05┬▒0.94 | 0.02┬▒0.15 | 0.03┬▒0.17 | 749.00 | <0.001** | 1.07 | 0.30 | 0.87 | 0.35 | ||

| 4. Agoraphobic fear/avoidance | 1.49┬▒0.94 | 1.72┬▒1.01 | 0.03┬▒0.18 | 0.01┬▒0.10 | 471.70 | <0.001** | 2.02 | 0.16 | 3.09 | 0.08 | ||

| 5. Panic-related sensation fear/avoidance | 1.46┬▒1.01 | 1.50┬▒0.99 | 0.01┬▒0.11 | 0.01┬▒0.10 | 384.81 | <0.001** | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.79 | ||

| 6. Impairment in work functioning | 1.42┬▒1.04 | 1.70┬▒1.03 | 0.02┬▒0.15 | 0.02┬▒0.14 | 391.22 | <0.001** | 3.02 | 0.08 | 3.14 | 0.08 | ||

| 7. Impairment in social functioning | 1.38┬▒0.97 | 1.74┬▒1.05 | 0.00┬▒0.00 | 0.02┬▒0.14 | 431.33 | <0.001** | 6.57 | 0.01 | 5.25 | 0.02* | ||

| Panic-agoraphobic symptoms | ||||||||||||

| APPQ total score | 53.85┬▒40.15 | 64.86┬▒45.51 | 18.56┬▒15.35 | 15.08┬▒12.91 | 162.45 | <0.001** | 1.28 | 0.26 | 4.72 | 0.03* | ||

| 1. Agoraphobia subscale | 20.45┬▒15.91 | 23.99┬▒17.99 | 4.79┬▒5.66 | 3.72┬▒4.67 | 187.03 | <0.001** | 1.043 | 0.31 | 3.39 | 0.07 | ||

| 2. Social phobia subscale | 17.75┬▒17.08 | 22.16┬▒18.59 | 8.40┬▒8.16 | 7.43┬▒7.14 | 70.89 | <0.001** | 1.15 | 0.23 | 3.53 | 0.06 | ||

| 3. Interoceptive fear subscale | 15.52┬▒13.37 | 19.42┬▒14.62 | 5.39┬▒5.56 | 3.94┬▒4.41 | 135.75 | <0.001** | 1.24 | 0.27 | 5.91 | 0.02* | ||

| Depressive symptoms | ||||||||||||

| BDI-II total score | 15.38┬▒8.98 | 17.19┬▒9.80 | 4.82┬▒4.58 | 4.86┬▒4.51 | 235.77 | <0.001** | 1.54 | 0.22 | 1.41 | 0.24 | ||

| Anxiety sensitivity | ||||||||||||

| ASI-R total score | 48.80┬▒27.23 | 52.83┬▒27.23 | 9.06┬▒9.81 | 7.67┬▒9.42 | 369.76 | <0.001** | 0.36 | 0.55 | 1.50 | 0.22 | ||

| Functional impairment | ||||||||||||

| SDS total score | 12.31┬▒8.35 | 14.65┬▒7.22 | 1.30┬▒3.19 | 0.47┬▒1.38 | 336.74 | <0.001** | 1.22 | 0.27 | 5.33 | 0.02* | ||

| 1. Work/school | 4.59┬▒3.23 | 5.39┬▒2.93 | 0.51┬▒1.33 | 0.23┬▒0.64 | 288.97 | <0.001** | 0.93 | 0.34 | 4.03 | 0.045* | ||

| 2. Social life | 3.92┬▒3.12 | 4.81┬▒2.82 | 0.40┬▒1.07 | 0.01┬▒0.38 | 247.12 | <0.001** | 1.48 | 0.22 | 4.84 | 0.03* | ||

| 3. Family life/home responsibilities | 3.75┬▒2.93 | 4.60┬▒2.82 | 0.39┬▒1.45 | 0.14┬▒0.50 | 254.41 | <0.001** | 1.33 | 0.25 | 5.32 | 0.02* | ||

REFERENCES

- TOOLS