Spousal Concordance and Cross-Disorder Concordance of Mental Disorders: A Nationwide Cohort Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Although both partners of a married couple can have mental disorders, the concordant and cross-concordant categories of disorders in couples remain unclear. Using national psychiatric population-based data only from patients with mental disorders, we examined married couples with mental disorders to examine spousal concordance and cross-disorder concordance across the full spectrum of mental disorders.

Methods

Data from the 1997 to 2012 Taiwan Psychiatric Inpatient Medical Claims data set were used and a total of 662 married couples were obtained. Concordance of mental disorders was determined if both spouses were diagnosed with mental disorder of an identical category in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; otherwise, cross-concordance was reported.

Results

According to Cohen’s kappa coefficient, the most concordant mental disorder in couples was substance use disorder, followed by bipolar disorder. Depressive and anxiety disorders were the most common cross-concordant mental disorders, followed by bipolar disorder. The prevalence of the spousal concordance of mental disorders differed by monthly income and the couple’s age disparity.

Conclusion

Evidence of spousal concordance and cross-concordance for mental disorders may highlight the necessity of understanding the social context of marriage in the etiology of mental illness. Identifying the risk factors from a common environment attributable to mental disorders may enhance public health strategies to prevent and improve chronic mental illness of married couples.

INTRODUCTION

Mental disorders affect a considerable portion of the global population and carry a high disease burden [1,2]. Numerous studies have reported that genetic factors contribute to the etiology of mental disorders [3].However, research has also documented cases of spousal concordance, which is where married couples, who are not genetically related, develop the same mental disorder. Spousal concordance often occurs across major mental disorders [4,5]. Studies have revealed that the existence of one partner’s mental disorder may increase the spouse’s risk of having another mental disorder, such as depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or substance use disorder, a phenomenon known as cross-disorder concordance [6-8]. The cross-disorder concordance of mental disorders may be common among married couples, but it has rarely been investigated. Thus, the present study investigated this topic.

Theories of assortative mating and emotional contagion may partially explain the mechanisms of spousal concordance for mental disorders. Assortative mating refers to the tendency to choose mates who share similar demographic characteristics, values, attitudes, and personality traits [9,10]. Through the formation of concordant health behaviours [11-15] in shared environments [16], assortative mating may play an essential role in the development of spousal concordance with mental disorders, such as anxiety and depressive disorders and alcohol dependence [4,17-19]. By contrast, theories of emotional contagion suggest that spouses mutually experience emotional states because of their interdependent relationship [6,14,20,21]. According to this perspective, cohabitation effects, such as a shared household environment, lifestyle, and life events [22,23], may lead to shared emotional symptoms such as depression and anxiety [24,25].

Social stratification [26,27] may play a role in the mechanism underlying the spousal concordance of mental disorders; however, findings on the causal relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and mental disorders remain inconsistent [28]. Generally, researchers have determined that SES is negatively related to mental disorders [29]. The concordance of mental disorders in socially disadvantaged groups, such as couples with mental disorders, is rarely discussed in the literature. Moreover, studies have had methodological limitations, such as a focus on only inpatients and a lack of consideration paid to other related factors [18,30] that induce spousal concordance. Regarding the age of onset of mental illnesses, for about half of mental disorders onset occurs well before age 18 [31]. However, dementia or other late-onset mental disorders often develop at an older age. For examining the effect of one mentally ill spouse on the other spouse, age is also a major related factor. Using national data on patients with mental disorders, this study examined both individuals in couples with mental disorders to examine the occurrence of spousal concordance and cross-disorder concordance across the full spectrum of mental disorders.

METHODS

Data source

The Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) is a medical claims database representing more than 99.7% of Taiwan’s population [32]; the database is maintained by the National Health Research Institute and the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan. The Psychiatric Inpatient Medical Claims (PIMC), a data set of the NHIRD, only contain information on patients with at least one psychiatric hospital admission record and one discharge diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at China Medical University Hospital, Taiwan (approval ID: CRREC-104-012).

Study sample

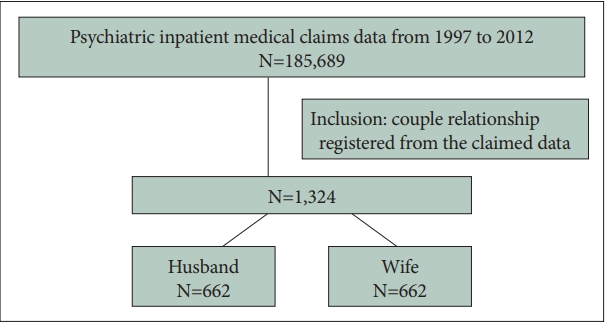

Participants were enrolled from 1997–2012 from the insurance registry of the PIMC if one partner was a National Health Insurance holder and the spouse was a dependent of the insured partner. Two individuals were regarded as a married couple when they coded as ‘spouse’ in the data field ‘relation’ and if the encrypted identifiers of the two spouses mutually matched. This method yielded a total of 662 married couples comprising 1,324 individuals (662 insured individuals and 662 dependent spouses) out of 185,689 subjects in PIMC for further analysis (Figure 1). Patients diagnosed with mental disorders (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]: 290.x–319.x) before 1997 were excluded from the study.

Patient and public involvement statement

This study used secondary data for analysis and did not involve patients or the public in the design, conduct, reporting and disseminating plans of the research.

Variables

Anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, substance use disorders, alcoholism, dementia, schizophrenia, and sleep disorders were the most common categories of mental disorders that presented in the data set. Considering the theories of emotional contagion and affect similarity, this study examined all types of affective disorders rather than depression only. The categories of mental disorders of the dependent spouse served as the outcome variable, and the categories of mental disorders of the insured individual served as the main independent variable. A married couple was determined to have a concordance of mental disorders if both spouses were diagnosed with mental disorder of an identical category in the ICD-9-CM; otherwise, cross-concordance was reported. The ICD-9-CM codes of mental disorders and the full spectrum of mental disorders are listed in Supplementary Tables 1-4 (in the online-only Data Supplement). Eight mental disorders were analysed in this study because of their high prevalence among couples.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of major categories of mental disorders in husbands and wives from 1998 to 2012 was ranked in terms of their numbers and percentages. The presence of a concordance of a mental disorder was determined using 2×2 contingency tables with Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ) [33]. According to Cohen, the kappa value indicates the level of agreement; specifically, κ≤0 indicates no agreement, 0<κ≤0.2 indicates slight agreement, 0.2<κ≤0.4 indicates fair agreement, 0.4< κ≤0.6 indicates moderate agreement, 0.6<κ≤0.8 indicates substantial agreement, and 0.8<κ≤1.0 indicates near-perfect agreement. Because of income inequality and age disparity among the insurers, the researchers conducted stratification tests for major mental disorders based on income and age. The statistical power was 0.87, which met the conventionally acceptable power of 0.8. Each of the stratified analyses provided sufficient statistical power. All tests were two-sided and had a significance level of α<0.05. Data were analysed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

The demographic data of 662 couples and the major categories of mental disorders among husbands and wives are presented in Table 1. The mean ages of husbands and wives are 48.1±15.6 and 54.9±18.1 years (mean±standard deviation), respectively. The most prevalent mental disorders among husbands were anxiety disorder (74.5%), depressive disorder (59.4%), bipolar disorder (42.0%), and schizophrenia (42.0%). The most prevalent mental disorders among wives were anxiety disorder (77.3%), depressive disorder (66.2%), and bipolar disorder (53.8%). Husbands had higher incidence of substance use disorder (30.5%) than their wives did, and wives had higher rates of mood-related disorders than their husbands did.

The concordant and cross-concordant mental disorders between couples are listed in Table 2. The most to least prevalent mental disorders were anxiety disorder (61.9%), depressive disorder (44.0%), bipolar disorder (29.8%), schizophrenia (28.4%), sleep disorder (14.4%), substance use disorder (10.9%), dementia (8.9%), and alcohol use disorder (3.3%). Because of the abundance of data, only the first and second cross-concordant mental disorders are presented in Table 2. Depressive and anxiety disorders were the most common cross-concordant mental disorders (49.6%), followed by bipolar disorder (38.6%). The most concordant mental disorder in couples was substance use disorder (κ=0.2845), followed by bipolar disorder (κ=0.2836).

Concordance and cross-cordance of major mental disorders among married couples by prevalence (Cohen’s kappa coefficient, N=1,324 psychiatric patients)

Stratification analyses by the insured individual’s monthly income level and age were conducted (Tables 3 and 4, respectively). Among married couples whose insured spouse had a premium-based monthly salary <US$667, the highest concordant mental disorder was bipolar disorder (κ=0.2996, p<0.001), followed by schizophrenia (κ=0.2320, p<0.001). Among married couples whose insured spouse had a premium-based monthly salary of US$667–US$1,332, the highest concordant mental disorder was dementia (κ=0.2828, p< 0.001), followed by substance use disorder (κ=0.2800, p<0.001). Among married couples whose insured spouse had a premium-based monthly salary ≥US$1,333, the highest concordant mental disorder was substance use disorder (κ=0.2710, p= 0.004), followed by schizophrenia (κ=0.2087, p=0.039).

Concordance of major mental disorders among couples by prevalence for each monthly income bracket (κ, N=662 couples)

Concordance of major mental disorders among couples by age disparity, in order of prevalence (Cohen’s kappa coefficient, N=662 couples)

As indicated in Table 4, among couples with an age disparity <10 years, the highest concordant mental disorder in couples was dementia (κ=0.3757, p<0.001), followed by schizophrenia (κ=0.3211, p<0.001) and anxiety disorder (κ=0.2956, p<0.001). Among couples with an age disparity ≥10 years, the highest concordant mental disorder was substance use disorder (κ=0.3800, p<0.001), followed by bipolar disorder (κ=0.3298, p<0.001). However, the concordance of anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, and dementia was not statistically significant among the couples with an age disparity ≥10 years.

DISCUSSION

This study examined couple concordance in a sample of Taiwanese individuals across a complete spectrum of mental disorders. This study did so by analyzing the PIMC data set, which covers only patients who had ever admitted to a psychiatric ward. The results of this study indicated that varying magnitudes of anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, substance use disorder, dementia, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, alcohol use disorder, and sleep disorder were highly common and concordant in couples. The most to least concordant mental disorders were substance use disorder, bipolar disorder, dementia, schizophrenia, anxiety disorder, sleep disorder, depressive disorder, substance use disorder, and alcohol use disorder. The results demonstrated that an insured spouse with a psychiatric disorder was more likely to have a dependent spouse with the same psychiatric disorder. Depressive and anxiety disorders were the most common cross-disorder concordant mental disorders among couples in this study. The high concordance and cross-concordance rates may have resulted from the fact that the study data was retrieved from the PIMC, which includes only data on patients with mental disorders.

This study addressed two mechanisms underlying spousal concordance as described in Introduction-assortative mating and emotional contagion [30,34]. Nordsletten et al.5’s study reported that people with mental disorders were two to three times more likely than people in the general population to have a romantic partner with a mental disorder. People often gravitate toward romantic partners who are similar to themselves. Because we only analysed patients with mental disorders, we noted a higher rate of concordance or cross-concordance of mental disorders. According to the theory of emotional contagion, which suggests that spouses mutually experience affective or emotional states [20], the familial context in which one spouse lives is closely linked with the psychological well-being of the other spouse. According to the stress process model [35], when a spouse is mentally ill, the partner is an essential caretaker who may endure primary and secondary stressors. If an individual was diagnosed with anxiety disorder, the spouse would most likely develop anxiety disorder. The concordance findings of this study are consistent with the patterns of anxiety anxiety, affective affective, and other (disorder) other (disorder) concordance, per the phenomenon of parallel contagion [6]. Wang et al. [6], however, expanded the concordance phenomenon to more specific psychiatric categories (Tables 2-4). Furthermore, if one spouse experiences bipolar disorder, the other spouse might experience another type of mental disorder, and the association of the mental disorders between the couples could be cross-concordant. Although an interdependent relationship of spousal emotional states was determined, such an effect was not universally equal among couples because of gender differences [15,25].

Regarding substance use disorders, family studies have revealed a high magnitude of spousal concordance for substance use disorders, such as tobacco use and alcohol use disorder [4,11]. Because married couples spend much of their lives together, alcohol consumption patterns are likely to be similar between spouses. Assortative mating, defined as a tendency to marry a person who already has similar traits, is a likely mechanism for spousal concordance, as indicated by the increased rate of substance use disorders among the relatives of people with substance use disorders [36,37]. In a previous study, high spousal concordance in substance use disorders was related to similar tension-reduction coping strategies in couples [38].

Income status and age disparity

We observed that the concordance rate in dependent spouses was highly associated with the insurer’s monthly income across all mental disorders. However, among couples with a high monthly income (≥US$1,333), anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, and alcohol use disorder were less concordant. Low household income has been linked to high occurrences of psychiatric morbidity, such as anxiety, mood disorders, substance use disorders, and suicide attempts [39]. According to downward drift hypothesis, the relationship between mental illness and social class, is the argument that illness causes one to have a downward shift in social class [40]. The circumstances of one’s social class do not cause the onset of a mental disorder, but rather, resulting in an individual’s deteriorating mental health and low social class attainment [27]. Low SES impacts the development of mental illness directly, as well as indirectly through its association with adverse economic stressful conditions among lower income groups.

We found that spouses of a similar age had concordance of the same mental disorder to varying degrees. However, if the spouses had an age difference of more than 10 years, the concordance of anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, and dementia would not be the case. For example, in a family of couples both with mental disorders, their age gap was more than 10 years, if one spouse had dementia, his (or her) couple may have another mental disorder instead of dementia. According to a large-scale meta-analysis, several disorders, such as anxiety, depressive, and bipolar disorders, tended to onset at later adulthood [31] but men and women do not differ with respect to the age of onset of mental disorders. Although mental disorders have various onsets from childhood, through adolescence, to adulthood, that involve dramatic biological changes in the brain [41]. There is substantial variation in the mating pattern according to diagnosis and age disparity of the couples.

This study has several limitations. First, some essential clinical information (e.g., marriage duration, quality of relationship, men’s effect on women, and women’s effect on men) was not included in the PIMC database, and such factors may influence couple concordance in either direction. Second, information concerning health behavior and perceived stress was also not included in the PIMC data set, and the lack of such information might limit the robustness of the study results. Lastly, couples concordant with a mood disorder are at greater risk of divorce compared with couples in which only one partner is diagnosed with a mood disorder [18]; this may partially explain the higher rates of concordance of mental disorders in couples in this study.

The present study also has several strengths. First, the PIMC database was representative of the Taiwanese population and includes only individuals with a mental disorder, and this minimized selection bias. Second, we analyzed real-world data using a retrospective cohort design to provide more realistic findings. Third, we explored the full spectrum of mental disorders among patients with mental disorders.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine comprehensive concordance and discordance of psychiatric disorders among married couples who had undergone hospitalisation. Evidence for spousal concordance and cross-concordance in mental disorders may highlight the large influence of social context, specifically of marriage, in the etiology of mental illness; this challenges the foundational assumption of current genetic research and constitutes a direction for further research [42]. A category of mental disorder in one spouse may implicate the occurrence of spousal concordance and cross-disorder concordance. Therefore, couple-based mental health intervention or even implementation of couple-oriented health insurance scheme—couplitation [43,44], which may improve early spousal examination in a manner paralleling capitation, merit more attention.

Public health policy is better served if policy makers better understand the environmental risk factors for mental disorders, especially those pertaining to couples sharing a common environment.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2022.0009.

ICD-9-CM of major categories of mental disorders

ICD-9-CM of minor categories of mental disorders

Mental disorders in husbands and wives by prevalence (N=662 couples)

Concordance and discordance of mental disorders among married couples by ICD-9-CM code (Cohen’s kappa coefficient, N=1,324 psychiatric patients)

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed during the study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Cheng-Chen Chang, Jeng-Yuan Chiou. Data curation: Yu-Hsun Wang, Jong-Yi Wang. Formal analysis: Yu-Hsun Wang, Jong-Yi Wang. Funding acquisition: Po-Chung Ju, Jong-Yi Wang. Investigation: Ming-Hong Hsieh, Jeng-Yuan Chiou, Yu-Hsun Wang. Methodology: Cheng-Chen Chang, Jeng-Yuan Chiou, Jong-Yi Wang. Writing—original draft: Cheng-Chen Chang, Jong-Yi Wang. Writing—review & editing: Ming-Hong Hsieh, Po-Chung Ju.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (Grant No. MOST110-2410-H-039-001).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Taiwan’s National Health Research Institutes for providing the NHIRD.