INTRODUCTION

Somatic symptoms commonly include cardiopulmonary, gastrointestinal, pain, and general symptoms [

1-

3]. Somatic symptoms in psychiatry include underlying depression, anxiety, or other psychiatric disorders [

4-

6]. People with such somatic symptoms often visit the department of internal medicine rather than visiting the department of psychiatry first. Specifically, after patients visit the department of internal medicine and are told that they have no specific abnormal finding, they finally visit the department of psychiatry. When examining such patients, psychiatrists may consider the section on ŌĆ£Somatic Symptom and Related DisordersŌĆØ in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) from a diagnostic perspective [

7]. In particular, doctors in charge needs to find out what somatic symptoms their patients have. In this case, the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) can be very useful [

8].

The PHQ is a tool that can easily screen depression, anxiety, alcohol, eating, and somatic symptom-related mental disorders when diagnosing patients. The PHQ has been translated into over 20 languages, and is widely used worldwide [

9,

10]. In particular, the PHQ-15 is a PHQ version that can detect somatic symptoms, and is a tool for measuring the type and severity of somatic symptoms that patients are currently complaining of. In South Korea, the PHQ-15 was assessed in a validation study by Han and his colleagues, and has being utilized usefully so far [

11]. The Somatic Symptoms Scale-8 (SSS-8), which is intended to be verified in this study is a short form of the PHQ-15.

The SSS-8 is composed of a total of 8 items excluding items regarding menstrual problems, sexual problems, and fainting contained in the PHQ-15. It was originally developed by Kroenke et al. [

8], and known as the PHQ-Somatic Symptom Short-Form [

12]. However, the validation study for this tool was conducted by Gierk et al. [

13] in Germany, and its name was changed to SSS-8, accordingly. That study proved that the internal consistency of SSS-8 was suitable, and revealed that it consisted of a 4-factor structure (gastrointestinal, pain, fatigue, and cardiopulmonary). In addition, that study classified severity into 5 categories, and proposed severity categories to easily check the severity of symptoms. Following this, a validation study for a Japanese version of the SSS-8 was conducted, and also verified its reliability and validity [

14]. Furthermore, that Japanese study verified the known-group validity, and explained somatic symptoms according to group. As found in the aforementioned previous studies, the SSS-8 is a useful tool to assess somatic symptoms and severity of patientsŌĆÖ complaints in a short time in the clinical settings. Despite the clinical usefulness of the SSS-8, the translation and validation of the SSS-8 has not been conducted in South Korea.

This study aimed to conduct a validation study of a Korean version of the SSS-8 (K-SSS-8), and to utilize the K-SSS-8 effectively in clinical settings.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the SSS-8 was translated into Korean language for local adaption, the reliability and validity of its Korean version, the K-SSS-8 was verified, and its clinical utility was investigated. The implications of the results are as follows.

First, the reliability analysis revealed that internal consistency and test-retest reliability were reliable. The internal consistency reliability of the K-SSS-8 was slightly better compared to previous studies (CronbachŌĆÖs alpha=0.81 in a study by Gierk et al.) [

13]. Test-retest reliability could not be compared because it had not been verified in previous studies [

13,

14]. However, in this study, the test-retest reliability of the K-SSS-8 was found to be a statistically reliable level [

21]. Taken together, the reliability of the K-SSS-8 can be judged to be reasonably high.

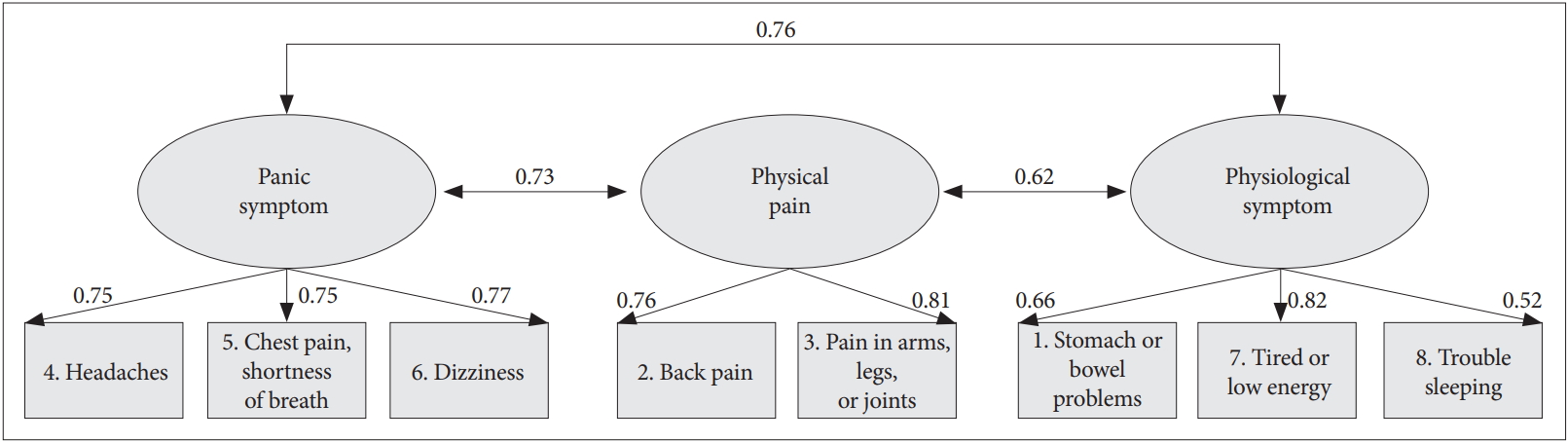

Next, the results of verifying the goodness-of-fit of the number of factors in the validity analysis showed that the 3-factor model was the most suitable. The explanatory variance explained by the three factors in the 3-factor model was also more than 70%, and the RMSEA value was less than 0.05, indicating ŌĆ£excellent.ŌĆØ [

18] In the EFA analysis, the 4-factor model showed an adequate goodness-of-fit, but in the CFA verifying the goodness-of-fit of the entire model, its goodness-of-fit was not satisfied. The reason is presumably thought to be due to the fact that when one factor was added from the 3-factor structure to the 4-factor structure, one item was assigned to the added factor. Because one factor can usually contain at least 2-3 items [

5,

22], the authors judged that it was not good in terms of economic feasibility and goodness-of-fit of the model when one item was generated as one factor [

23]. Meanwhile, this same problem occurred in the previous study by Gierk et al. [

13], but it seems that they selected a higher-order structure added with a general factor to solve with a 4-factor model. However, the authors of this study judged that the 3-factor model is adequate and concise for 8-item classification based on statistical theories. The implications of each factor in the 3-factor model are as follows.

The first factor was named as ŌĆ£Cardiopulmonary,ŌĆØ and included item #6: ŌĆ£Dizziness,ŌĆØ item #4: ŌĆ£Headaches,ŌĆØ and item #5: ŌĆ£Chest pain or shortness of breath.ŌĆØ In the study of Gierk et al. [

13], items #5 and #6 were grouped and expressed as cardiopulmonary symptoms. In this study, those 3 items were considered to be included in 13 types of Panic attack specifier in the DSM-5, and were thus named as ŌĆ£Cardiopulmonary.ŌĆØ Recently, the number of people complaining of panic-like symptoms is increasing, and the number of patients with panic disorder in hospitals is also increasing. The first factor ŌĆ£CardiopulmonaryŌĆØ is thought to be very useful in predicting people who are likely to develop panic disorder. So the first factor is likely that the mental health professionals will be able to identify symptoms easily, directly, and quickly. In particular, the items ŌĆ£Chest pain or shortness of breathŌĆØ and ŌĆ£DizzinessŌĆØ correspond to Panic disorder diagnosis criteria, so the factor can serve as evaluation items for diagnosis. On the other hand, the ŌĆ£HeadachesŌĆØ question is included, which is not consistent with the question of diagnose for the Panic disorder, but is a symptom that is often followed with Panic disorder. Unlike the findings of Gierk and his colleagues, the ŌĆ£HeadachesŌĆØ question was included in the ŌĆ£CardiopulmonaryŌĆØ factor, perhaps due to differences in cultural background. When complaining of cardiopulmonary function problems, Koreans tend to complain of dizziness and headaches. It would be better to conduct a replication study on this part.

The second factor ŌĆ£PainŌĆØ included item #3: ŌĆ£Pain in your arm, legs, or joints,ŌĆØ and item #2: ŌĆ£Back pain.ŌĆØ The second factor literally means physical or body pain, and is thought to be common in patients with physical illness. In the study by Gierk et al. [

13], it was also named ŌĆ£PainŌĆØ factor. The second factor, ŌĆ£PainŌĆØ is thought to be very useful for detecting symptoms which appear on the surface of the body, such as the back and joints. The second factor includes pain in the back and joints, and when responding to questions related to ŌĆ£Pain,ŌĆØ it seems that physical of surgical problems may be considered first. If the patient complains of symptoms related to the ŌĆ£PainŌĆØ factor even after excluding physical or surgical problems, the mental health professionals may consider ŌĆ£Somatic Symptoms and Related Disorders.ŌĆØ

Finally, the third factor, ŌĆ£Gastrointestinal and FatigueŌĆØ included item #1: ŌĆ£Stomach or bowel problems,ŌĆØ item #7: ŌĆ£Feeling tired or having low energy,ŌĆØ and item #8: ŌĆ£Trouble sleeping.ŌĆØ The third factor is mainly related to physiological symptoms, which are often accompanied by complaints of somatic symptoms. This factor is thought to be closely related to digestive problems, sleep problems, and decreased vitality which are commonly observed in patients with depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, somatic symptoms, and related disorders. It is thought that the third factor enables us to quickly detect the presence or absence of physiological symptoms through the third factor. The third factor includes stomach and fatigue problems. From a psychiatric perspective, these problems are often accompanied by depression and anxiety. Therefore, there may be cognitive and emotional depression and anxiety at the basis of patients with gastrointestinal symptoms and fatigue, and in this case, it is recommended to conduct an additional scale related to depression and anxiety. Unlike Gierk et al. [

13] findings, the ŌĆ£stomach and bowel problemsŌĆØ item was included in the ŌĆ£fatigueŌĆØ factor, which may be due to differences in cultural background. Koreans are known to be primarily accompanied by fatigue and gastrointestinal problems when stressed. Also, it would be better to have a replication study on this part.

In this study, Known-group validity was also verified using a Jonckheere-Terpstra test. According to the participantsŌĆÖ responses (depression) to the PHQ-2, the participants were divided into three groups (group 1: depression-positive for both items; group 2: depression-positive for one item; and group 3: depression-negative for both items). The verification showed that there was a significant difference in the total K-SSS-8 score according to the degree of depression. Similarly, in terms of PHQ-15 and EQ-5D, there was a significance difference in the total scores between the groups. These results suggest that depression may be closely related to the complaint of somatic symptoms [

6,

24]. It is known that 50-70% of patients with somatic symptoms and related disorders have a comorbid mental disorder, usually accompanied by depression and anxiety [

7]. Therefore, for patients complaining of somatic symptoms, it may be necessary to examine more thoroughly through interviews or measurements whether they have underlying depression or anxiety [

25].

In addition, frequency analysis according to the severity of the K-SSS-8 was performed for healthy control and patient groups in this study. In the case of the healthy control participants, the proportion of those who had higher than ŌĆ£mediumŌĆØ severity was 43.2%, which is twice as high as in Japan (20.6%) [

14]. These results may be due to the fact that the participants were limited to public officers as the healthy control population, and it is thought that about half of these participants had at least 2-3 somatic symptoms.

In the case of the patient group, the proportion of those who had higher than ŌĆ£mediumŌĆØ severity was 65.1%, unlike the control group, and about 2/3 of the participants in the patient group complained of at least 2-3 somatic symptoms. Diagnostically, more than 90% of them had been diagnosed with depression or anxiety-related disorders, and had no medical abnormalities. It is known that a significant number of patients who complained of somatic symptoms without a medical condition initially visited the internal medicine departments [

26]. This suggests that consultation between internal medicine and psychiatry departments is required, and the importance of consultation [

27].

Taken together, in terms of clinical utility, the K-SSS-8 can be useful for exploring symptoms such as panic symptoms, physical pain, and physiological symptoms experienced by patients in a short time. In addition, the K-SSS-8 is expected to be very useful for determining the current severity by using the severity categories and for establish additionally required assessment plans for depression and anxiety symptoms. In particular, a K-SSS-8 score of 12 or higher is common in the patient group, but not common in the healthy control group. Therefore, ŌĆ£severe complaints of somatic symptomsŌĆØ should be considered when establishing treatment plans.

The K-SSS-8 is also thought to be useful in therapeutic aspects. Since the K-SSS-9 was divided into three factors (Cardiopulmonary, Pain, Gastrointestinal and Fatigue), it is thought that it will help to establish a pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy plan based on main symptoms. For example, it is known that the effect size of combined therapy (pharmacotherapy plus cognitive behavior therapy) is high for panic symptoms, and that when physiological symptoms are dominant, it is appropriate to consider pharmacotherapy first [

28-

30].

Lastly, the limitations and future research directions of this study are as follows: First, the factor analysis revealed that the number (n=167) of the participant of this study was within an appropriate range, but it is recommended that the number (n) of participants is more than 200 participants to improve the power of a test [

31]. In addition, frequency analysis was performed with the data from the patient group, but it seems that it is desirable for the numbers of participants to be more than 50 so as to increase the power of a test. Second, severity levels could be identified using severity categories. However, cut-off scores are always used valuably in clinical settings. Therefore, it is considered that future studies are needed to investigate the total K-SSS-8 scores for patients with somatic symptoms and related disorders and to present cut-off scores through the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Third, if complaints about somatic symptoms are common in patients with depression and anxiety disorders, it is considered necessary to perform K-SSS-8 analysis according to such disorders. With regard to depression and anxiety disorders, related study findings such as the distribution of total scores, distribution of scores for each factor, and cut-off score estimation for each disorder through ROC analysis are thought to be very useful in actual clinical settings.