The Effect of Cognitive Training in a Day Care Center in Patients with Early Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia: A Retrospective Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of cognitive training programs on the progression of dementia in patients with early stage Alzheimer’s disease dementia (ADD) at the day care center.

Methods

From January 2015 to December 2018, a total of 119 patients with early ADD were evaluated. All subjects were classified into two groups according to participate in cognitive training program in addition to usual standard clinical care. Changes in scores for minimental status examination-dementia screening (MMSE-DS) and clinical dementia rating-sum of boxes (CDR-SOB) during the 12 months were compared between two groups. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed.

Results

As compared to case-subjects (n=43), the MMSE-DS and CDR-SOB scores were significantly worse at 12 months in the control-subjects (n=76). A statistically significant difference between the two groups was observed due to changes in MMSE-DS (p=0.012) and CDR-SOB (p<0.001) scores. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that the cognitive training program (odds ratio and 95% confidence interval: 0.225, 0.070–0.725) was independently associated with less progression of ADD.

Conclusion

The cognitive training program was associated with benefits in maintaining cognitive function for patients with early-stage ADD that were receiving medical treatment.

INTRODUCTION

The population of South Korea is aging very rapidly due to the world’s lowest birth rate and the extension of the average life expectancy in the country. The predicted life expectancy in South Korea will become the highest in the world, beyond Japan and France [1]. Owing to the rapid aging, the number of dementia patients in South Korea exceeded 700,000 in 2017 and is expected to increase rapidly to 1 million in 2024 and 1.5 million in 2034 [2]. Thus, the burden of dementia patients and for their families will increase rapidly, and the social burden to manage them will also increase exponentially. In response, the Korean government has actively engaged in policy intervention on dementia management issues, ranging from the comprehensive plan announced by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in 2008 to the National Responsibility System for dementia announced in September 2017 [3,4].

One of the major policies to reduce the burden of care for dementia patients and caregivers is the introduction of long-term care insurance. After the introduction of the special level (5th level) of long-term care insurance for dementia patients in 2014, this was expanded to include mild dementia patients who had not yet received benefits [5,6]. This includes support for the use of day care centers and cognitive training programs. Since the implementation of the national responsibility for dementia, the benefit from long-term care insurance has been expanded to a wider range of early dementia patients in terms of cognitive support level. After this revision, most of the patients with early stage of dementia were able to use the day care center and cognitive training program [7,8].

Day care centers for people with dementia is known to reduce the burden of caregivers [9]. At this point, it is necessary to analyze how the use of cognitive training programs in day care centers helps to maintain and support the cognitive function of dementia patients in addition to reducing the burden for caregivers.

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of cognitive training programs on the progression of dementia in patients with early stage Alzheimer’s disease dementia (ADD) at the day care center. It would give more information to determine the appropriate policy intervention for early dementia patients by examining the changes in cognitive function, according to the current status of participation in a cognitive training program.

METHODS

Study population

We retrospectively analyzed medical records from patients with ADD who were included in the local dementia mass screening program of the Namyangju City public health center between January 2015 and December 2018. This program was conducted for residents in the city who were aged 60 or older. The inclusion criteria of this study were: 1) diagnosed as clinically probable ADD by criteria of the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association Standard (NINDS) [10], 2) with mild (early-stage) symptoms [Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) ≤1] [11], 3) had received an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, and 4) performed cognitive function tests 12 months after initial assessment.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) any primary neurodegenerative or psychiatric disorder other than ADD (i.e., Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder) [12,13], 2) diagnosed as clinically possible, probable, or definite vascular dementia by criteria of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–the Association pour la Recherche et l’Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS-AIREN) [14], 3) brain tumor or severe traumatic brain injury, 4) any history of drug or alcohol addiction within the past 2 years, 5) cases of medical diseases (liver disease, kidney disease, or thyroid disease) that cause cognitive function decline, and 6) any physical disability (hearing or visual impairment) that could significantly impair the evaluation of the patient or cognitive training program.

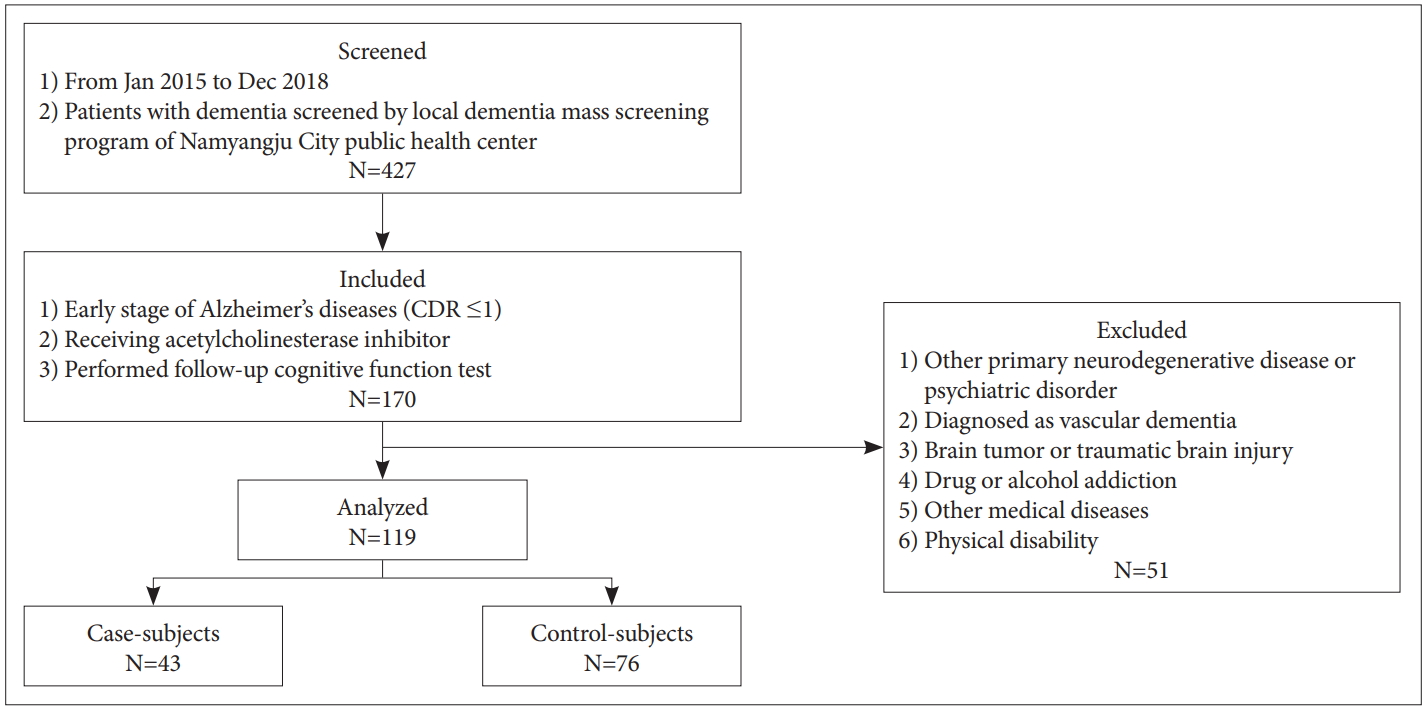

All subjects were classified into two groups (Figure 1). The case-subjects had regularly visited the day care center (which is provided as a service from long-term care insurance), were taking the cognitive training program, and received the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. The control-subjects continued to receive the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor without visiting day care center or taking cognitive training. All patients underwent physical and neurological examination. Demographic and clinical information including age, sex, education, vascular risk factor (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, and cardiovascular disease), and medication history were collected. The time point at which the patients initially underwent brain imaging (CT or MRI) and neuropsychological tests, including mini-mental status examination-dementia screening (MMSE-DS), Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), and Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Diseases (CERAD) by the local dementia mass screening program were considered to be the baseline [15]. Follow-up neuropsychological tests [MMSE-DS, CDR, and sum-of-boxes (CDR-SOB)], which were conducted 12 months after baseline, were compared between the two groups. The MMSE-DS is a Korean version of the MMSE, which has been validated with standardized norms [16]. We defined progression of ADD as an increase in CDR-SOB score by ≥2 points at 12 months [17]. Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Hanyang University Guri Hospital (2020-03-008).

Cognitive training in the day care center

The cognitive training program was designed and assessed using standard guidelines for coordinating dementia support center. The cognitive training was administered 3 hours in a day, 5 days a week, and for 12 months at each day care center. There was an instructor at each of day care center, who was an experienced clinical neuropsychologist. Programs included attention training (i.e., paper or computer assisted attention training), memory training (i.e., training in the recall of a list and remembering the location of objects in the room), visuoconstruction training (i.e., drawing various things and changing blocks), physical training (i.e., massed calisthenics), occupational training (i.e., creative activity such as drawing or knitting), and speech training.

Statistics

We performed Fisher’s exact tests to compare proportions and the Mann-Whitney U test and Student’s t-test for continuous variables to evaluate differences between the groups. Changes in cognitive assessment scores (MMSE-DS and CDR-SOB scores) between baseline and the follow-up point were analyzed by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The scores of the two groups for baseline and follow-up points, were compared using Mann-Whitney. Correlation between ADD progression and patient characteristics were evaluated by logistic regression analysis. Adjusted variables were age, sex, and factors which were significant (p value <0.1) in the univariate analysis. Two-tailed p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant, and all statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 package for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Overall, 427 dementia patients were screened by the local dementia mass screening program of the Namyangju City public health center between January 2015 and December 2018. Among them, 170 patients were diagnosed as early-stage ADD (CDR ≤1); patients underwent follow-up neurocognitive function tests, and received acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. After excluding patients who met the exclusion criteria, a total of 119 patients were included in this study (Figure 1). Patient ages ranged from 67 to 89 years [mean (±SD) was 78.0 (±4.4) years].

The number of patients who received both cognitive training and standard clinical care (case-subjects) was 43 and the number of patients who received only standard clinical care (control-subjects) was 76. The baseline characteristics of each group are shown in Table 1. Progression of ADD and dyslipidemia were identified more frequently in control-subjects and baseline CDR-SOB score was higher in case-subjects. Otherwise, there were no significant differences between the two groups.

As compared to case-subjects, the MMSE-DS and CDR-SOB scores significantly worsened at 12 months in the control-subjects (Table 2, Figure 2). The mean increase in the MMSE-DS scores in case-subjects (treated with both cognitive training and medication) during the 12 months was 0.45 points (p=0.248 vs. baseline), whereas the mean decrease in the MMSE-DS score in the control-subjects (treated with medication only) was 1.80 points (p<0.001 vs. baseline). The mean increase of the CDR-SOB score was 0.64 points (p=0.080 vs. baseline) in case-subjects, whereas the mean increase in CDR-SOB score was 2.82 points (p<0.001 vs. baseline) in control-subjects. A statistically significant difference between the two groups was observed in the changes in MMSE-DS and CDR-SOB scores (Figure 2).

MMSE-DS score changes and CDR-SOB scores in case and control subjects during the follow-up period. Note the significant preservation of MMSE-DS (p=0.012) and the CDR-SOB score (p<0.001) at 12 months in case subjects compared to the decrease in control subjects. Data are the means±SEM. Indicated p-value represents the difference in score change between two groups. *p<0.001 versus baseline. MMSE-DS: mini-mental status examination-dementia screening, CDR-SOB: Clinical Dementia Rating Scale sum of boxes.

Patient characteristics based on progression of dementia are shown in Table 3. Patients with progression of dementia had more dyslipidemia (p=0.011) and less cognitive training (p=0.002). Logistic regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, and p-value below 0.1 on univariate analysis (dyslipidemia, education, and cognitive training) showed additional cognitive training (odds ratio and 95% confidence interval: 0.225, 0.070–0.725) were independently associated with less progression of ADD (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In this study, application of a cognitive training program at a day care center in addition to usual standard clinical care showed significant benefit in terms of cognitive function in early ADD patients. In the management of ADD, pharmacological therapy helps to suppress the progression of symptoms, but it does not fundamentally change the progression of the disease. Accordingly, various non- pharmacological therapies have been attempted, including cognitive training programs, which have been identified as the most important non-pharmacological approach [18-23]. The results of our study demonstrated that cognitive function was maintained and that deterioration associated with the disease was also suppressed significantly in the group that continued to perform cognitive function training, even in patients who had been treated consistently with medication. This finding is consistent with previous studies that cognitive training can be effective in improving cognitive function and activities of daily living in dementia patients [24-28]. However, previous studies have primarily observed patients for a short-term period, and under intensive training program conditions. Therefore, the findings for comparison are limited and the impact of public services, such the provision of cognitive training programs by the long-term care insurance, are still being investigated. In particular, similar to our study, a study investigated the change in cognitive function, based on the provision of cognitive function programs by the grade of long-term care insurance in South Korea; however, the results were challenging to directly apply in the clinical field or for dementia-related policy because the clinical condition of the patients was not fully considered [6]. Therefore, our study is significant because it evaluated patient participation in a cognitive training program and changes in clinical symptoms, including cognitive function, which can be accurately tracked through medical records. In addition, the patient’s diagnosis and clinical severity can be accurately identified through comprehensive examination, including the cognitive function test and brain imaging that are conducted by a dementia specialist.

Dyslipidemia was independently associated with cognitive decline in this study. However it is difficult to interpret the meaning of this result in this study, owing to the small sample size and insufficient data for compliance with medications. Although there is a possibility for a correlation between dyslipidemia and cognitive decline in specific patients [29,30], the association between dyslipidemia and ADD is still controversial and requires additional research [31].

There were several limitations to this study. First, it was retrospectively designed, and has the possibility of significant selection bias. Therefore, we applied strict inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the medical records to try to reduce this bias. Second, as the time of enrollment was different for each participants, received cognitive training program might be different among them. However contents of the cognitive training programs are structured and do not make a big difference every year. Third, attendance and compliance rate for cognitive training was not monitored. It would be difficult for some participants to attend three hours of cognitive training for five days a week. But, it is also meaningful that application of a cognitive training program showed benefit although some of them might have low attendance rate. Fourth, biomarkers including magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography imaging, and cerebrospinal fluid study were not analyzed in this study. Fifth, lifestyle risk factors and burden of caregivers are not investigated. Finally, the sample size was small, therefore a study with a prospective design, standardized diagnostic workup including biomarkers, investigating life style risk factors and burden of caregivers, and larger number of participants may be warranted. However, considering the advantages of this study, the results are sufficiently suggestive for clinical sites.

Another factor to consider is that more than half of the early dementia patients who are constantly receiving medication do not receive cognitive training programs at their day care center. Therefore, it is necessary to consider not only the provision of the cognitive training programs at day care centers through long-term care insurance, but also ways to actively provide these programs throughout the medical field to make them more accessible for patients. In conclusion, the provision of cognitive training programs through long-term care insurance at day care centers have possibility to help maintain the cognitive function in early-stage ADD patients. Based on these results, these programs should be expanded in the future, and policies should consider the way to utilize these programs in the medical field.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the research fund of Hanyang University (HY-2017).

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Hyuk Sung Kwon, Hojin Choi. Data curation: Kyungtaek Yun, Jong Sook Baek, Young Un Kim. Formal analysis: Hyuk Sung Kwon, Seongho Park. Funding acquisition: Hojin Choi. Investigation: Hyuk Sung Kwon, Hojin Choi. Methodology: Hyuk Sung Kwon, Ha-rin Yang. Project administration: Hojin Choi. Supervision: Ha-rin Yang, Kyungtaek Yun, Jong Sook Baek, Young Un Kim. Validation: Hyuk Sung Kwon, Ha-rin Yang. Visualization: Hyuk Sung Kwon. Writing—original draft: Hyuk Sung Kwon. Writing—review & editing: Seongho Park, Hojin Choi.