Defining Subtypes in Children with Nail Biting: A Latent Profile Analysis of Personality

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to examine personality profiles and behavioral problems of children with nail biting (NB) to gain insight into the developmental trajectory of pathological NB.

Methods

681 elementary school students were divided into non NB (n=436), occasional NB (n=173) and frequent NB group (n=72) depending on the frequency of NB reported in Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL). Children’s personality was assessed using the Junior Temperament and Character Inventory (JTCI), and behavioral problems were assessed using the CBCL. Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) was performed using JTCI profiles to classify personalities of the children with NB (belonging to frequent and occasional NB group, n=245).

Results

For subscale scores of CBCL, the total, internalizing, externalizing, anxious/depressed withdrawn/depressed, depression, thought, rule-breaking, and aggressive behavior problems, were most severe in the frequent NB group followed by occasional NB and non NB group. LPA of personality profile in children with NB revealed four classes (‘adaptiveness,’ ‘high reward dependence,’ ‘low self-directedness,’ and ‘maldaptiveness’). The four personality classes demonstrated significant group differences in all of the CBCL subscales. Children who showed low self-directedness and cooperativeness and high novelty seeking and harm avoidance personality profiles demonstrated highest tendency for problematic behavior irrespective of the frequency of NB.

Conclusion

Children with NB reported significantly more problematic behaviors compared to children without NB. Children with specific personality profile demonstrated higher tendency for problematic behavior irrespective of the frequency of NB. Therefore, accompanying personality profiles should be considered when assessing behavioral problems in children with NB.

INTRODUCTION

Nail biting (NB), also known as onychophagia, is defined as the act of putting one or more fingers in the mouth or biting the fingernails with teeth [1]. NB has been reported to start in childhood and decrease with adulthood [2]. The exact prevalence rate is unknown, but it has been reported to be 28–33% in school age children, 44% in adolescents and 19–29% in adults [3-5]. NB is a relatively common and benign condition in practical situations [6]. In some cases, however, NB causes irreversible shortening of finger nails, gum injury, temporomandibular disorder and malocclusion [7-10]. In rare cases, it damages surrounding nail tissues, causing infections and tooth root damage [11-14].

With respect to the clinical aspects of NB, research suggests tension reduction and emotion regulation are common driving motives [15]. In a recent large-scale study, NB of adulthood has been reported to be associated with borderline personality trait and low self-esteem and is part of a single pathological grooming disorder factor characterized by body-focused repetitive behavior, along with skin picking and hair pulling [16]. Furthermore, NB may present with high rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (74.6%), oppositional defiant disorder (36%), separation anxiety disorder (20.6%) and enuresis (15.6%) in school-aged youth [17]. Therefore, investigation of nonclinical childhood NB can give initial insight into the developmental trajectory of pathological NB.

There are few studies on NB in childhood. In a study of 743 primary school students, NB severity, emotion, and behavioral problems were investigated [3]. As a result, children with NB had more conduct behavior, emotional problems and lower prosocial behavior than the control group. After adjusting for other variables, NB was less associated with prosocial behavior. However, this study used a brief tool, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, for evaluating emotional behavior problem and reported a significantly lower NB rate in comparison to previous studies, thus requiring cautious interpretation. In another study of children with deleterious oral habits including NB, depression severity correlated positively with salivary cortisol levels, and presence of oral habits was associated with anxiety [18]. The study only evaluated anxiety and depression and did not use a comprehensive assessment for the emotion-behavior domain. In addition, the number of control subjects was insufficient. In order to examine behavioral problems in children with NB, large sample studies using comprehensive psychological assessment tools are needed.

Severity of NB is classified according to the level of dermal injury or frequency [19]. For example, in a 1999 study, individuals with severe NB and mild NB reported different physiological arousal and reduction of stress [19]. However, NB is known to have a high comorbidity rate [17], and classifying NB only according to the severity of the dermal injury may be insufficient for clinical usefulness. In the present study, in addition to characterizing behavioral problems in NB by severity level, we hypothesized that personality factors may underlie problematic behaviors in children with NB.

The Junior Temperament and Character Inventory (JTCI) was used for the investigation of the personality factors in child with NB. NB has not been investigated previously in regard to personal temperament and character [20-22]. According to the Cloninger’s biosocial model, classifying individuals based on personality differences could be important contribution to the better understanding of NB psychopathology independent from psychological condition [23-25].

Latent profile analysis (LPA) can be used to find the distinct subtypes of the children’s temperament and character with respect to NB. LPA is a person-centered statistical method, used to identify latent subgroups or subtypes of cases by examining how individuals naturally group together [26]. The main advantage of the LPA is that it can identify a pattern of shared symptoms in a sample [27].

This study aimed to examine personality profiles and behavioral problems of children with NB to gain insight into the developmental trajectory of pathological NB. First, we compared the personality and behavioral characteristics between children with NB and children without NB in a community-based sample. Next, we explored the association between personality profiles and problem behaviors in children with NB.

MEHTODS

Participants

As a cross sectional design, this study used the results of the emotional and behavioral problem evaluation conducted as a part of a school violence prevention project of the National Center for Mental Health, Republic of Korea. The An emotion-behavior questionnaire and a computerized attention test was conducted for all school students in selected pilot schools for the purpose of preventing school violence and screening for high risk mental health children. Detailed information was provided to all parents, and signed informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents prior to enrollment. After obtaining consent, questionnaires were distributed to participants and their caregivers, and the Continuous Performance Tests were conducted. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Center for Mental Health (116271-2018-44). In this study, students from 1st to 6th grade in one elementary school in Seoul were recruited (age range: 6–11), and finally, a total of 681 students who agreed to the study completed the questionnaire.

Measures

Child Behavior Checklist and classification of NB groups

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) is a widely used standardized method of identifying childhood psychological behavioral problems by parent report [28]. The CBCL includes 113 items divided into 2 broad ranged syndromes (internalizing and externalizing problems) and 8 syndrome scale scores (anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaint, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, rule-breaking behavior, and aggressive behavior) and internalizing problems consist of withdrawn/depressed, anxious/depressed, and somatic complaints. Higher scores indicate worse symptoms. In the present study, we used the Korean version of the K-CBCL which has been validated with satisfactory internal consistency and international validity [29]. We classified the children into groups: non NB (0, not true), occasional NB (1, somewhat or sometimes true), and frequent NB (2, very true or often true), depending on the response to the CBCL item of “bites fingernails.”

Junior Temperament and Character Inventory (JTCI)

The JTCI is based on Cloninger’s biosocial model of personality [30]. A total of 108 questions are designed for yes or no answers to each question. It consists of four temperaments (harm avoidance, novelty seeking, reward dependence, and persistence) and three character dimensions (cooperativeness, self-directedness, and self-transcendence). The Korean version for parents was used with Cronbach alpha of 0.48–0.80 for the temperament scales and 0.64 to 0.68 for the character scales. Test-retest correlations ranged from 0.62 to 0.85 for the temperament scales and from 0.76 to 0.79 for the character scales.

Statistical analysis

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants according to the NB frequency groups (Non NB, occasional NB and frequent NB) were analyzed using χ2 tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. To classify the distinct subtype of children with NB (occasional & frequent group, n=254), we performed LPA with the seven subscale of JTCI as indicator variables. Model solutions were determined on the basis of the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and entropy [31]. BIC is a commonly used and reliable method of model fit determination which means better fit with lower BIC values [32]. Entropy is an index that indicates the accuracy of assigning latent class membership. Higher probability value indicates more accurate classification. Comparisons between classes of continuous variables, including CBCL subscales, were conducted by ANOVA. Classes were compared on gender and grade using χ2 tests.

To protect from Type I error, a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied. The adjusted p value will be the alpha-value divided by the number of comparisons (n): (adjusted alpha=0.05/n). The adjusted p value is described in each table. Analyses were executed using the SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R. Statistical significance was defined as a p value<0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the nail biting frequency groups (non NB vs. occasional NB vs. frequent NB)

A total of 681 children were recruited. We divided the children according to their response to item 44 of CBCL (nail biting frequency group: non NB, occasional NB, and frequent NB). Of the total, 436 respondents (non NB) answered ‘not true’ to the item “bites fingernails” in CBCL, and 173 responded ‘sometimes true’ (occasional NB) and 72 responded ‘very true or often true’ (frequent NB). Table 1 shows the demographic data for each NB frequency group. There was no significant difference except for age among the three groups. Non NB group was younger than the other two groups.

Comparison of the JTCI among the nail biting frequency groups

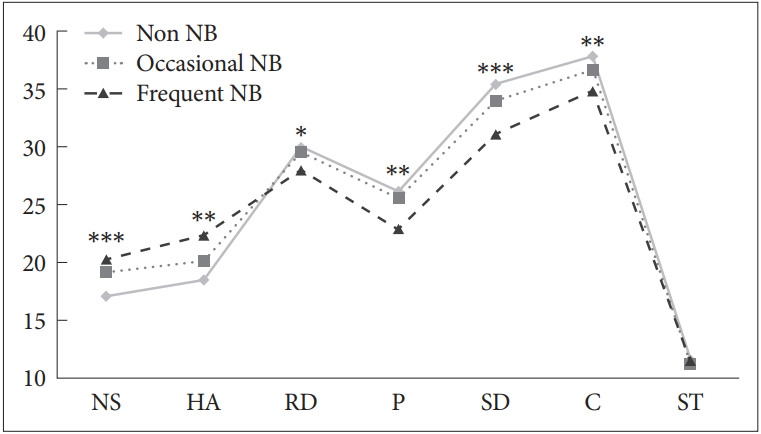

The difference between the NB frequency groups according to the subscales of the JTCI is presented in Table 2 and Figure 1. The differences among the three NB frequency groups in novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, persistence, self-directedness and cooperativeness were significant even after the Bonferroni correction. Post hoc test using the Scheffe test confirmed statistically significant differences between the non NB group and the frequent NB group in all of the JTCI profiles except self-transcendence.

Comparison of the JTCI among the nail biting (NB) frequency groups (non NB, occasional NB, frequent NB). The difference between the NB frequency groups in JTCI scales (novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, persistence, self-directedness and cooperativeness) was significant after Bonferroni correction. The Scheffe test showed that there was significant group difference between the non NB group and the frequent NB group in all of the JTCI profiles except Self-transcendence (ST). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.0001. NS: novelty seeking, HA: harm avoidance, RD: reward dependence, P: persistence, SD: self-directedness, C: cooperativeness, ST: self-transcendence.

Comparison of the CBCL among the nail biting frequency groups

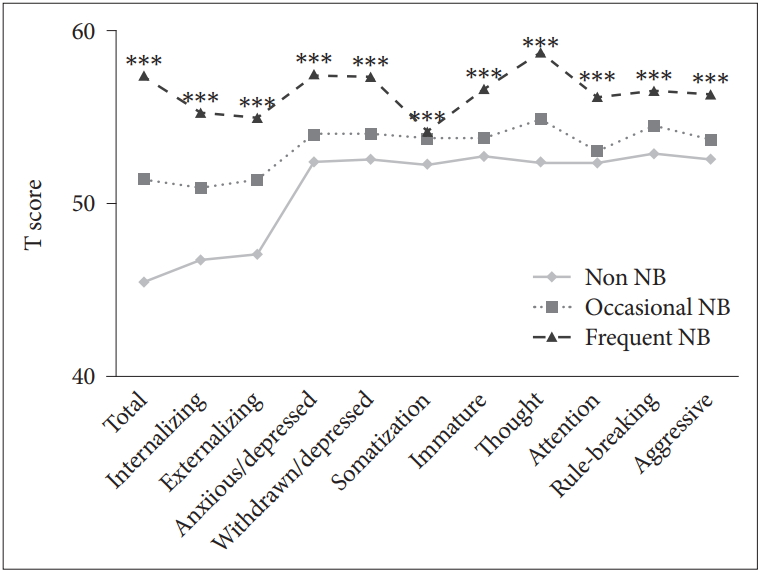

All subscale scores of the CBCL between the three NB frequency groups were significantly different after Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. The total, internalizing, externalizing, anxious/depressed, depression, withdrawn/depressed, thought, rule-breaking, aggressive and miscellaneous behavioral problems were most severe in the frequent NB group, second severe in the occasional NB group, and least severe in the non NB group. The somatization subscale showed a significant difference between NB group and the non NB group, but there was no significant difference between the frequent and occasional NB group. Also, the attention problem subscale and the immature subscale were significantly higher in the frequent NB group than in the other groups, but there was no significant difference between the occasional NB group and the non NB group (Table 3, Figure 2).

Comparison of the CBCL among the NB frequency groups. All subscale scores of CBCL between the three NB frequency groups were significantly different after Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. The total, internalizing, externalizing, anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, thought, rule-breaking, and aggressive behavior problems measured by CBCL, were most severe in the frequent NB group, followed by occasional NB group and non NB group. ***p<0.0001. CBCL: Child behavior Checklist, NB: nail biting.

Classification of children with NB using the JTCI

As a result of LPA, the statistical criteria suggested that a four-class solution was the best modeling of the heterogeneity of the data. Four class solution (BIC=11,190.72, entropy=0.888) yielded smallest BIC compared to two class (BIC=11,300.06, entropy=0.935), three class (BIC=11,256.85, entropy=0.893), five class (BIC= 11,201.05, entropy=0.885) and six solution (BIC=11201.671, entropy=0.888). The four-class solution consisted of class 1, labeled ‘adaptiveness’ (n=80; 32.65%); class 2, labeled ‘high reward dependence’ (n=58; 23.67%); class 3, labeled ‘low self-directedness’ (n=62; 25.31%); and class 4, labeled ‘maladaptiveness’ (n=45; 18.37%) (Table 4). Class 1 (adaptiveness), which constituted the largest subgroup, had the highest level self-directedness and cooperativeness among the four classes. Class 2 (high reward dependence) showed the second highest novelty seeking, self-directedness, and cooperativeness values among all classes. Class 3 (low self-directedness) was characterized by low levels of reward dependence and persistence across all classes. Class 4 (maladaptiveness), which is composed of the smallest number of participants, characteristically shows the lowest self-directedness and cooperativeness level and the highest novelty seeking and harm avoidance among the four classes.

Characteristics of four latent classes of personality in children with NB

The demographic characteristics of the four latent classes of personality in children with NB, were analyzed using the chi-square test. As a result, there were no significant difference in age, sex, family income and parental education level. There was also no significant association between the NB frequency (according to CBCL item 44) and the four latent classes of personality in children with NB, χ2 (3, n=245)=14.14, p=0.079.

A comparison of CBCL subscales between four latent classes showed statistically significant differences after Bonferroni correction in all subscales (Table 5, Figure 3). In total problems and externalizing problem subscale, class 4 (maladaptiveness) had the highest score, and class 1 (adaptiveness) had the lowest score, but there was no statistically significant difference between class 3 (low self-directedness) and class 2 (high reward dependence). The internalizing problems subscale scores were higher in the order of class 4 (maladaptiveness), class 3 (low self-directedness), class 2 (high reward dependence) and class 1 (adaptiveness), but there was no statistically significant difference between class 4 (maladaptiveness) and class 3 (low self-directedness) and between class 2 (high reward dependence) and class 1 (adaptiveness).

CBCL comparisons among four classes of children with NB. There was statistically significant differences among four latent classes in children with NB after Bonferroni correction in all CBCL subscales. In total problems, class 4 (maladaptiveness) had the highest score, and class 1 (adaptiveness) had the lowest score. The internalizing problem subscale scores were higher in the order of class 4 (maladaptiveness), class 3 (low self directedness), class 2 (high reward dependence), class 1 (adaptiveness). The externalizing problem subscale score was also statistically significant, with the highest level of class 4 (maladaptiveness) and the lowest level of class 1 (adaptiveness). ***p<0.0001. CBCL: Child Behavior Checklist, NB: nail biting.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to explore the association between personality profile and problem behaviors in children with NB. First, we compared the personality and behavioral characteristics between children with NB and children without NB in a community-based sample. Next, we explored the association between personality profile and problem behaviors in children with NB.

A previous study compared the personality of 130 subjects with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) to 185 healthy subjects and found that higher harm avoidance scores and lower reward dependence, self-directedness and cooperativeness scores [33]. Consistent with the previous study, we show that youth whose parents endorsed frequent NB on the CBCL showed higher harm avoidance and significantly lower reward dependence, self-directedness and cooperativeness in personality compared to children without NB. This personality similarity between OCD and NB supports the classification of trichotillomania and skin picking, which are reported to share similar psychopathology to NB, as obsessive compulsive and related disorders in DSM-5 [16,34]. However, the distinction between OCD and NB is that novelty seeking was reported to be low in the previous study of OCD but higher in youth with NB in the current study [35].

In a study of trichotillomania, one of the other pathological grooming disorders, novelty seeking was also high [36] Previous research have found a population association between D4 dopamine receptor gene and the normal personality trait of novelty seeking [37]. The high novelty seeking in youth with NB support greater dopaminergic involvement and indicate that the impulsivity aspect must be considered in the classification of pathological grooming disorders including trichotillomania, skin picking and NB.

Our findings reveal distinct subtypes of children with NB. Children who belong to class 1 (adaptiveness), who showed the highest level self-directedness and cooperativeness among the four classes, and class 2 (high reward dependence), who showed slightly lesser compared to Class 1 but still high level of self-directedness and cooperativeness, had less severe behavioral problems compared to the children belonging to class 3 (low self-directedness) and class 4 (maladaptiveness) who generally showed low levels of self-directedness and cooperativeness. Among the children with NB, the difference between classes with and without problematic behavior is high persistence, high reward dependence and high self-directedness. The class with the above three characteristics (low persistence, low reward dependence, low self-directedness) have reported association with resilience in previous studies [38,39]. Therefore, these three characteristics of high persistence, high reward dependence and high self-directedness, could reflect a protective resilience factor for the development of psychopathology in youth with NB.

Class 3 (low self-directedness), who demonstrated the lowest reward dependence and persistence among four classes, had no significant differences in CBCL internalizing, withdrawn/depressed, somatization and thought problem compared to Class 4 (maladaptiveness), who showed the lowest self-directedness and cooperativeness level and the highest novelty seeking and harm avoidance. Personality profiles of children belonging to Class 3 (low self-directedness), who showed high levels of harm avoidance and low levels of novelty seeking, reward dependence, self-directedness and persistence, is consistent with the personality profiles of patients with anxiety disorders, which is characterized by high harm avoidance and low novelty seeking and self-directedness [40]. In a previous study, comorbidity in youth (aged 5 to 18 years) with NB who visited psychiatric clinics was examined [17], and anxiety disorder was comorbid in about 20% of youth with NB [17]. Therefore, we can speculated that class 3 (low self-directedness) may represent a possible group of children susceptible to anxiety disorders. In addition, children with NB in Class 4 (maladaptiveness) are the most vulnerable of the children with NB, interventions focused on functional impairment and externalizing comorbidity may be helpful for children with NB who showed temperament profile similar to Class 4 (maladativenes); low self-directedness and cooperativeness and high novelty seeking and harm avoidance.

In the same previous study of comorbid conditions in youth with NB visiting psychiatric clinics, the most common coexisting condition was reported to be attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [17]. In the present study, the attention problems subscale of the CBCL was significantly different among the three NB frequency groups. In a report with small samples (n=20) on neurocognitive findings of skin picking, a disease entity similar to NB, impairments of motor inhibition was observed [41]. In the replication study with slightly larger samples (n=55), emotion-based impulsivity (tendency to act rashly under extreme negative or positive emotion) showed significant differences between children with skin picking and controls [42]. In the current study, emotion-based impulsivity was not directly measured. However, consistent with results of the previous studies, there was a significant difference among the groups (non NB vs. occasional NB vs. frequent NB) in terms of novelty seeking (rapid reactive) and reward dependence, which are known to be highly related to impulsivity. Therefore, NB may be associated with impulsivity similar to the pathological skin picking disorder. Further research is needed to clarify the etiology of pathological grooming disorder including NB, skin picking and trichotillomania.

It should be noted that this study investigated a community sample and not a clinic referred sample. Due to referral biases, it is difficult to investigate the nature of NB itself in clinically referred patients in which comorbid conditions are prevalent and severe. Another noteworthy feature is that the extent of problematic behaviors was regardless of frequency of NB. There was no significant difference in the distribution of the four latent classes of personality in children with NB according to frequency of NB in this study. Therefore, clinical considerations of personality factors for development of problematic behaviors in children with NB should be conducted closely, regardless of the frequency of the biting habit.

In the current study, NB was evaluated only by a single item of the parent-reported CBCL. Moreover, since this study relies on the report of the caregiver, there is a possibility that it will be influenced by the subjectivity of the parents. It is also possible that the caregiver may not accurately recognize the child’s behavioral status. In particular, NB may have been underestimated as it may have gone unrecognized by the parents. Lastly, we did not investigate the presence of NB habit in the past. Therefore, it is possible that a child who had a NB habit in the past may be assigned as the control group.

In this study, we observed that children with NB, which was generally thought of as a benign behavior, have significantly more problematic behaviors compared to children without NB. When the children with NB were classified into subgroups according to personality profiles, it was found that the participants with NB who showed lowest self-directedness and cooperativeness and highest novelty seeking and harm avoidance personality profiles have highest tendencies for problematic behavior irrespective of the frequency of NB. Therefore, accompanying personality profiles should be considered when assessing behavioral problems in children with NB.

Acknowledgements

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest. This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant number: HI18C1180). The findings and conclusions in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agency. No author reports any competing financial interests. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the ‘Psychiatry Investigation.’

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Yunhye Oh,Yeni Kim. Data curation: Yunhye Oh, Yeni Kim. Formal analysis: Yunhye Oh. Funding acquisition: Yeni Kim. Investigation: Yunhye Oh, Yeni Kim. Methodology: Yunhye Oh, Yeni Kim. Project administration: Jungwon Choi, Yul-Mai Song, Kyungun Jhung, Young-Ryeol Lee, Yeni Kim. Resources: Young-Ryeol Lee, Yeni Kim. Supervision: Yeni Kim. Validation: Yunhye Oh, Yeni Kim. Visualization: Yunhye Oh, Nam-Hee Yoo. Writing—original draft: Yunhye Oh. Writing— review&editing: Yunhye Oh, Kyungun Jhung, Nam-Hee Yoo, Yeni Kim.