Standardized Patients or Conventional Lecture for Teaching Communication Skills to Undergraduate Medical Students: A Randomized Controlled Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The conduct of a medical interview is a challenging skill, even for the most qualified physicians. Since a training is needed to acquire the necessary skills to conduct an interview with a patient, we compared role-play with standardized patients (SP) training and a conventional lecture for the acquisition of communications skills in undergraduate medical students.

Methods

An entire promotion of third year undergraduate medical students, who never received any lessons about communications skills, were randomized into 4 arms: 1) SP 2 months before the testing of medical communications skills (SP); 2) conventional lecture 2 months before the testing (CL); 3) two control groups (CG) without any intervention, tested either at the beginning of the study or two months later. Students were blindly assessed by trained physicians with a modified 17-items Calgary-Cambridge scale.

Results

388 students (98.7%) participated. SP performed better than CL, with significant statistical differences regarding 5 skills: the use of open and closed questions, encouraging patient responses, inviting the patient to clarify the missing items, encouraging of the patient’s emotions, and managing the time and the conduct of the interview. The SP group specifically improved communications skills between the SP training and testing sessions regarding 2 skills: the use of open and closed questions and encouraging patient responses. No improvements in communications skills were observed in CG between the two time points, ruling out a possible time effect.

Conclusion

Role-play with standardized patients appears more efficient than conventional lecture to acquire communication skills in undergraduate medical students.

INTRODUCTION

The conduct of a medical interview is a challenging skill, even for the most qualified physicians. Several objectives should be achieved in the same time, such as gathering precise and valid medical information, establishing a climate of trust and empathy, and providing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies [1]. A set of interpersonal skills is required during the medical interview to obtain the confidence of the subject. The building of patient confidence is a process called “engagement” and results to what is traditionally called an alliance. In order to succeed the engagement process, the physician will need interpersonal skills that can be trained such as providing empathy, sense of security, authenticity, and competence [1]. It is now established that a good communication between physicians and patients can lead to better patient compliance, and better satisfaction with the care received [2]. However communication skills -defined here as interpersonal skills- need to be trained as other medical skills, as initial but also continuing training for physicians, otherwise they will deteriorated [3].

Since a practice is needed to acquire the necessary skills during the interview with a patient, most medical schools now integrate specialized training to teach communication skills [4]. Training strategies include oral presentation, modeling by watching others (reality or video), small group discussions, peer role-play and role play with standardized patients (SP) [5]. Increasing attention exists regarding SP programs that have proven efficacy in teaching communication skills to students [5-7]. SP can be played by actors, real patients or physicians, who are trained to follow predefined scenarios and to provide standardized responses. SP programs integrate the opportunity of standardization between sessions. The reproducibility of the sessions allows to examine communication skills with a good reliability between students [8].

The use of such interactive trainings have been compared to more conventional didactic methods like learning in a manual, and have proved superiority in the acquisition of communication skills [9]. However, up to date, no studies assessed the efficacy of role-play with SP in teaching communication skills versus a lecture, which is the very most used didactic method [10]. Moreover, such study is expected as the interactive training programs based on role-play and SP are shown to be effective but are more time and cost consuming than conventional lectures [11]. In this context, we decided to develop in our university a simulation-based education program conducted in a dedicated simulation center that promotes simulation in healthcare education. SP programs to train communication skills were developed for undergraduate medical students. We conducted a randomized study to compare role-play with SP training and a conventional lecture for the acquisition of communication skills in undergraduate medical students. Our hypothesis was that students trained with SP would have higher ratings in objective communication skill measures assessed with the Calgary modified guide.

METHODS

Population of students

The study was approved by the local education authorities (Paris 7 UFR Medecine).

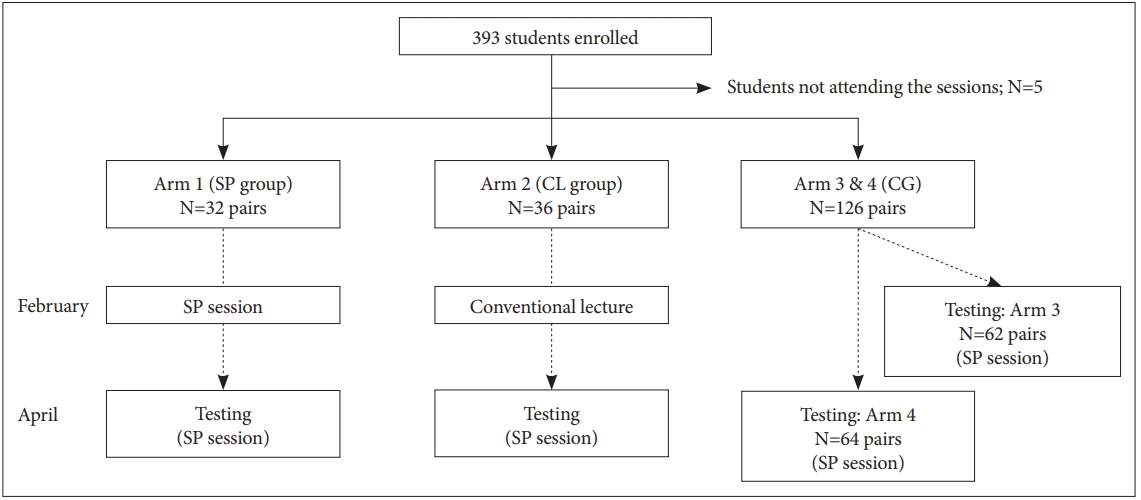

An entire promotion of third year undergraduate medical students who never received any lessons about medical communication skills were randomized into 4 arms: 1) SP training 2 months before the testing of medical communications skills (SP group); 2) conventional lecture training 2 months before the testing (CL group); 3) two control groups (CG) without any intervention (Figure 1).

Flowchart of students enrolled and randomized into four arms. CL: conventional lecture, CG: control groups, SP: standardized patients.

Testing of communication skills was performed by a standardized-patient session, 2 months after the initial training protocol for SP and CL group. Scenarios were different in March and April to avoid a learning bias in the SP group (Supplementary Materials in the online-only Data Supplement). For control groups 1 and 2, medical communications skills were assessed by a standardized-patient session at two time points: either at the beginning of the study (control group 1) or two months after (control group 2), to take into account the effects of bedside teaching in hospitals (Figure 1).

Standardized patients’ sessions

Students were divided in groups of 4. Each group of 4 trainees was under the supervision of one tutor, which was a graduated medical doctor. Two SP were interviewed at each session. Two trainees were conducting the interviews of the first SP, while the tutor was taking notes outside of the room behind a one-way glass, with the 2 other trainees observing the relational skills of their colleagues. The position of the trainees was switched for the interview of the second SP. All students were randomly paired and given a short preparation time before conducting the interview together. At the end of the interview, trainees were given feedback by the tutors, the SP and the observing trainees. Scenarios were based on typical presentations of common conditions (Supplementary Materials in the online-only Data Supplement). Students had only access to information regarding the current situation of each SP. The actors were trained graduated medical doctors. Their scenario included a detailed medical information about the patient background, lifestyle and history to ensure a good reproducibility between groups [scenario are available in Supplementary Materials (in the online-only Data Supplement)].

Conventional lecture

The conventional lecture was a 2 hours lecture made by a trained psychiatrist (PAG) in a classroom, using slides projected on a large screen. The focus of the lecture was about communications skills and reviewed the main interpersonal skills and how to improve them. Students could ask questions in an interactive manner, and the course was illustrated by real-life clinical situations. In addition, the lecture included the main items of the Calgary Cambridge guide. All students from the CL group attended the course.

Assessment of communication skills

Tutors were blinded from students’ arms. At the end of each session, the tutors rated the communication skills following 17 items of a modified version of the Calgary-Cambridge guide [8,12]. Criteria were translated and modified to focus on concrete items that could easily be rated during the interviews (Table 1). Each criteria could be rated as not performed (score=0), present but insufficient (score=1) or correctly performed (score=2). The sum of scores were calculated for each paired student group. The principal judgment criteria of efficacy was the global score on the modified Calgary-Cambridge scale. Secondary criteria included self-rating scale assessing the pedagogical interest of each training method, on a scale ranging from 0 (no pedagogical interest) to 10 (the best pedagogical interest).

Statistical analyses

Mean and standard deviations were calculated for interview performances within groups. These performances assessed with the modified Calgary guide interview (Table 1) followed normal distributions and comparisons between groups were made using a t-test. A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistics were made using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Population

During the 2018–2019 academic year, 393 third-year undergraduate medical students were included at the Paris Diderot University. 388 students (98.7%) as well as 32 graduated medical doctors (tutors and actors) participated to the program of training communication skills.

In the SP groups, students were 32 pairs at the February training, and 18 pairs at the April testing. For the group that assisted to a conventional lecture in February and were trained with SP in April, they were 36 pairs. The two SP controlled groups of February were 62, and those in April were 64. Finally, 5 students did not assist from none of the groups (Figure 1).

Interview performances of medical students after a conventional lecture or a training with standardized patients

The SP group demonstrated better performances than students that were first trained with a conventional lecture, with 5 out of the 17 skills that were particularly improved by the SP training: the use of open and closed questions, encouraging patient responses, inviting the patient to clarify the missing items, encouraging of the patient’s emotions, and managing the time and the conduct of the interview (Table 2).

Interview performances of medical students after training with standardized patients

SP group students improved communications skills between the 2 SP sessions (February and April). Statistically significant differences regarding 2 out of the 17 skills were observed: the use of open and closed questions, and encouraging patient responses (Table 3).

To take into account the effects of the hospital bedside teaching that occurred at the same time, control groups tested with SP sessions in February (n=62) and April (n=64) were compared. They did not show any improvement in communications skills over time, ruling out a possible time effect (results not shown).

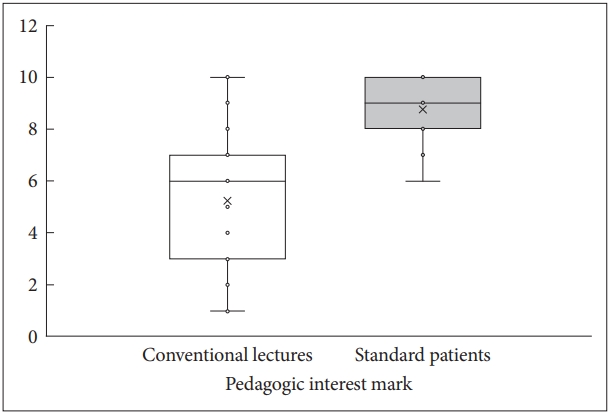

Self assessment of pedagogical interest by students

Students who had both the conventional lecture and the SP testing (CL group) found a clear better pedagogic interest of the SP training versus the conventional lecture (Student’s t= -7.56; p<0.001) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

In this randomized controlled study, we report a comparison between conventional lecture and SP session in teaching communication skills to undergraduate medical students. Our results showed that teaching with SP was associated with improved communication skills as compared to a conventional lecture. Moreover, we observed a significant improvement between the first and the second SP sessions, suggesting that despite a daily active bedside teaching, interviews with SP still provided additional training and contribute to the acquisition of relevant communication skills.

Among strengths of our study, the whole promotion of students was included, whereas most studies were based only on volunteers among medical students, which may have led to selection biases [9]. Moreover, students were randomized between groups, and the supervisors were blinded to student’s arms. All these conditions were required to avoid confounding factors such as imbalance between skills of students before starting the program, which are recognized major biases of such pedagogic studies [9].

Previous studies reported that lecture methods were considered too passive to properly develop the acquisition of communication skills, as compared to active methods such as SP [13,14]. In our study, students benefited from teaching with SP in the objective acquisition of skills, but also provided positive feedback about the pedagogical interest of the training. All students were successively interviewers and observers participating in the supervision of the interview. Thus, the trainees were encouraged to analyze their strengths and weakness following the Calgary Cambridge scale, which contributed to the acquisition of skills. Moreover, the availability of graduated physicians as tutors facilitated the interactivity in the groups and the experience sharing between students and tutors. This positive feedback has been linked to effective learning [15] and could contribute to a sustainable retention of skills, although our study did not assess the long term benefit of the program.

Some limits should be acknowledged. First, our data were collected immediately at the end of the SP sessions, and so the sustainability of acquired communication skills can not be assessed from this study. We cannot conclude regarding the longterm benefit from this short-term program. Moreover, some studies suggested that longer training programs (more than one day) would be more effective than shorter [5], and we did not compare different SP trainings according to their duration. The best results were from practical training programs as role play, that combined a didactic component with practical rehearsal and feedback [16]. Probably the best training program would include both lessons and SP session [17]. Moreover, flipped classroom has also demonstrated very interesting teaching results, with growing popularity, and could be combined or compared to SP in future studies [18]. Third, the evaluation of paired students may also have altered the results. Nevertheless, to ensure comparability between groups, even in the smallest group, students were trained by two to avoid confusing factors between arms, and so this may not have impacted the efficacy comparison. Finally, we may wonder whether the SP teaching program would have been more useful if it had been scheduled before reaching a real patient’s bedside (in second year), and if it could be repeated in higher grade students to teach more delicate skills such as teaching bad news. But although the implementation of the SP teaching program has been considered a success, the high cost of running such a program, as well as the necessity to recruit a large number of actors and tutors, may represent a limit to the generalization of this teaching approach.

Regarding cost assessments, significant human resources were necessary to carry out this educational program, but students reacted favorably to the SP training sessions and their learning significantly improved after training. Consequently, we concluded that Kirkpatrick’s level 2 was reached19 (accounting for the acquisition of skills) strongly encouraging us to continue this program in our University. Interestingly, SP training shows efficacy in teaching the communication skills in foreign medical students, too [20]. Future researches are also expected to compare different methods to evaluate reliably communication skills [21-23], as well as assessing the impact of these training on health outcomes [4].

Teaching communication skills with standardized patients programs was more efficient than a traditional lecture in undergraduate medical students. Nevertheless, the long-term sustainability of such acquisition and its consequences in building the patient-physician relationship need to be assessed.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2019.0258.

Acknowledgements

None.

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Pierre A. Geoffroy, Julie Delyon, Hugo Peyre. Data curation: Pierre A. Geoffroy, Isabelle Etienne. Formal analysis: Pierre A. Geoffroy, Julie Delyon, Hugo Peyre. Investigation: Pierre A. Geoffroy, Julie Delyon, Marion Strullu, Alexy Tran Dinh, Henri Duboc, Lara Zafrani, Hugo Peyre. Methodology: Pierre A. Geoffroy, Julie Delyon, Pierre-François Ceccaldi, Patrick Plaisance, Hugo Peyre. Project administration: Pierre A. Geoffroy, Julie Delyon, Pierre-François Ceccaldi, Patrick Plaisance, Hugo Peyre. Supervision: Michel Lejoyeux, Pierre-François Ceccaldi, Patrick Plaisance. Validation: Pierre-François Ceccaldi, Patrick Plaisance. Visualization: Pierre A. Geoffroy. Writing—original draft: Pierre A. Geoffroy, Julie Delyon. Writing—review & editing: Marion Strullu, Alexy Tran Dinh, Henri Duboc, Lara Zafrani, Isabelle Etienne, Michel Lejoyeux, PierreFrançois Ceccaldi, Patrick Plaisance, Hugo Peyre.